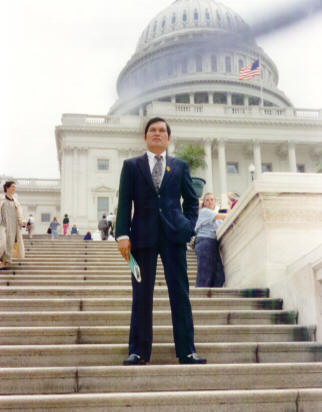

at Capitol. June 19.1996

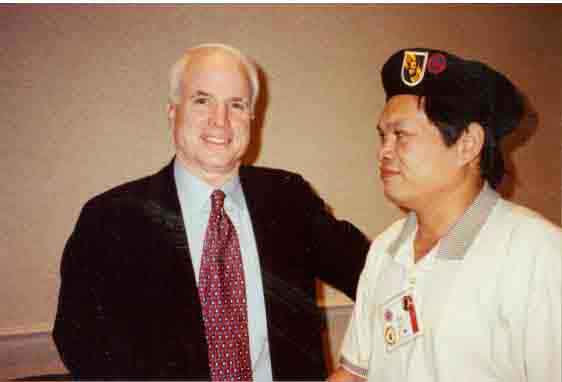

with Sen. JohnMc Cain

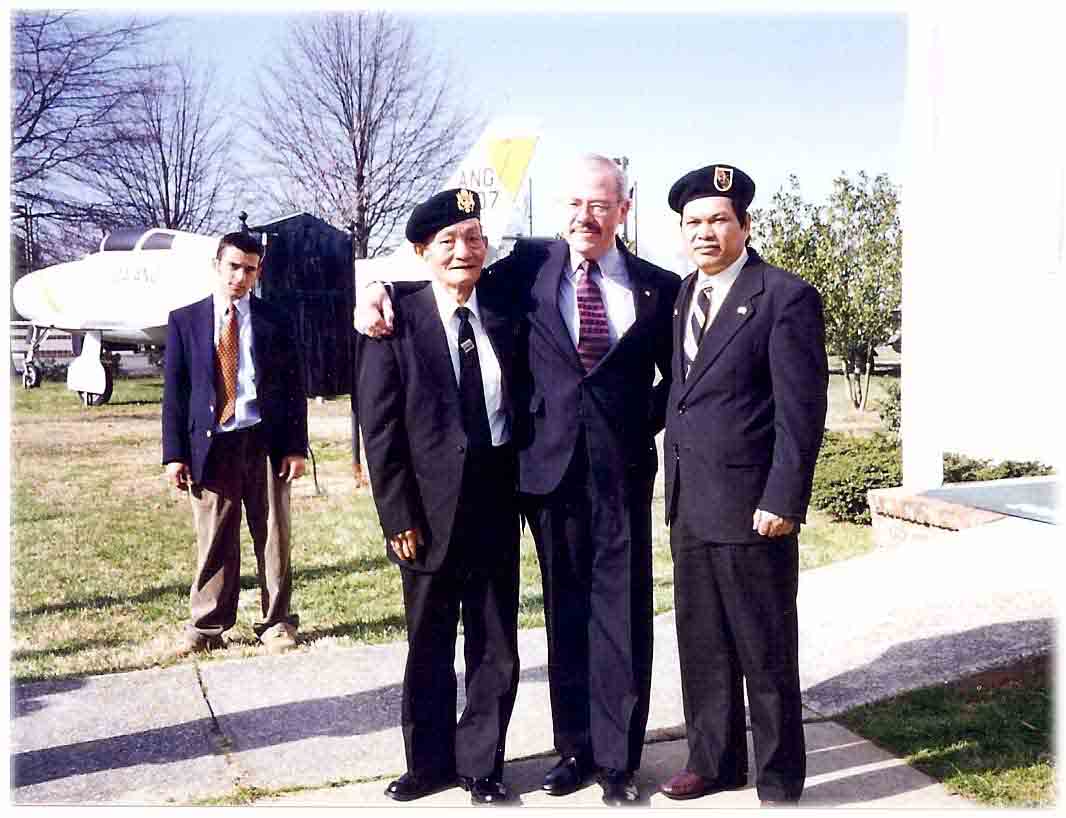

with Congressman Bob Barr

with General John K Singlaub

CNBC .Fox .FoxAtl .. CFR. CBS .CNN .VTV.

.WhiteHouse .NationalArchives .FedReBank

.Fed Register .Congr Record .History .CBO

.US Gov .CongRecord .C-SPAN .CFR .RedState

.VideosLibrary .NationalPriProject .Verge .Fee

.JudicialWatch .FRUS .WorldTribune .Slate

.Conspiracy .GloPolicy .Energy .CDP .Archive

.AkdartvInvestors .DeepState .ScieceDirect

.NatReview .Hill .Dailly .StateNation .WND

-RealClearPolitics .Zegnet .LawNews .NYPost

.SourceIntel .Intelnews .QZ .NewAme

.GloSec .GloIntel .GloResearch .GloPolitics

.Infowar .TownHall .Commieblaster .EXAMINER

.MediaBFCheck .FactReport .PolitiFact .IDEAL

.MediaCheck .Fact .Snopes .MediaMatters

.Diplomat .NEWSLINK .Newsweek .Salon

.OpenSecret .Sunlight .Pol Critique .

.N.W.Order .Illuminatti News.GlobalElite

.NewMax .CNS .DailyStorm .F.Policy .Whale

.Observe .Ame Progress .Fai .City .BusInsider

.Guardian .Political Insider .Law .Media .Above

.SourWatch .Wikileaks .Federalist .Ramussen

.Online Books .BREIBART.INTERCEIPT.PRWatch

.AmFreePress .Politico .Atlantic .PBS .WSWS

.NPRadio .ForeignTrade .Brookings .WTimes

.FAS .Millenium .Investors .ZeroHedge .DailySign

.Propublica .Inter Investigate .Intelligent Media

.Russia News .Tass Defense .Russia Militaty

.Scien&Tech .ACLU .Veteran .Gateway. DeepState

.Open Culture .Syndicate .Capital .Commodity

.DeepStateJournal .Create .Research .XinHua

.Nghiên Cứu QT .NCBiển Đông .Triết Chính Trị

.TVQG1 .TVQG .TVPG .BKVN .TVHoa Sen

.Ca Dao .HVCông Dân .HVNG .DấuHiệuThờiĐại

.BảoTàngLS.NghiênCứuLS .Nhân Quyền.Sài Gòn Báo

.Thời Đại.Văn Hiến .Sách Hiếm.Hợp Lưu

.Sức Khỏe .Vatican .Catholic .TS KhoaHọc

.KH.TV .Đại Kỷ Nguyên .Tinh Hoa .Danh Ngôn

.Viễn Đông .Người Việt.Việt Báo.Quán Văn

.TCCS .Việt Thức .Việt List .Việt Mỹ .Xây Dựng

.Phi Dũng .Hoa Vô Ưu.ChúngTa .Eurasia.

CaliToday .NVR .Phê Bình . TriThucVN

.Việt Luận .Nam Úc .Người Dân .Buddhism

.Tiền Phong .Xã Luận .VTV .HTV .Trí Thức

.Dân Trí .Tuổi Trẻ .Express .Tấm Gương

.Lao Động .Thanh Niên .Tiền Phong .MTG

.Echo .Sài Gòn .Luật Khoa .Văn Nghệ .SOTT

.ĐCS .Bắc Bộ Phủ .Ng.TDũng .Ba Sàm .CafeVN

.Văn Học .Điện Ảnh .VTC .Cục Lưu Trữ .SoHa

.ST/HTV .Thống Kê .Điều Ngự .VNM .Bình Dân

.Đà Lạt * Vấn Đề * Kẻ Sĩ * Lịch Sử *.Trái Chiều

.Tác Phẩm * Khào Cứu * Dịch Thuật * Tự Điển *

KIM ÂU -CHÍNHNGHĨA -TINH HOA - STKIM ÂU

CHÍNHNGHĨA MEDIA-VIETNAMESE COMMANDOS

BIÊTKÍCH -STATENATION - LƯUTRỮ -VIDEO/TV

DICTIONAIRIES -TÁCGỈA-TÁCPHẨM - BÁOCHÍ . WORLD - KHẢOCỨU - DỊCHTHUẬT -TỰĐIỂN -THAM KHẢO - VĂNHỌC - MỤCLỤC-POPULATION - WBANK - BNG ARCHIVES - POPMEC- POPSCIENCE - CONSTITUTION

VẤN ĐỀ - LÀMSAO - USFACT- POP - FDA EXPRESS. LAWFARE .WATCHDOG- THỜI THẾ - EIR.

ĐẶC BIỆT

-

The Invisible Government Dan Moot

-

The Invisible Government David Wise

ADVERTISEMENT

Le Monde -France24. Liberation- Center for Strategic

https://www.intelligencesquaredus.org/

Space - NASA - Space News - Nasa Flight - Children Defense

Pokemon.Game Info. Bách Việt Lĩnh Nam.US History

with Ross Perot, Billionaire

with General Micheal Ryan

US DEBT CLOCK .WORLDOMETERS .TRÍ TUỆ MỸ . SCHOLARSCIRCLE. CENSUS - SCIENTIFIC-COVERTACTION. EPOCH ĐKN - REALVOICE - JUSTNEWS - NEWSMAX - BREIBART - WARROOM - REDSTATE - PJMEDIA - EPV - REUTERS - AP - NTD REPUBLIC - VIỆT NAM - BBC - VOA - RFI - RFA - HOUSE - TỬ VI - VTV - HTV - PLUTO - BLAZE - INTERNET - SONY - CHINA SINHUA - FOXNATION - FOXNEWS - NBC - ESPN - SPORT - ABC- LEARNING - IMEDIA - NEWSLINK - WHITEHOUSE CONGRESS - FED REGISTER - OAN - DIỄN ĐÀN - UPI - IRAN - DUTCH - FRANCE 24 - MOSCOW - INDIA - NEWSNOW NEEDTOKNOW - REDVOICE - NEWSPUNCH - CDC - WHO - BLOOMBERG - WORLDTRIBUNE - WND - MSNBC- REALCLEAR

POPULIST PRESS - PBS - SCIENCE - HUMAN EVENT - REPUBLIC BRIEF - AWAKENER - TABLET - AMAC - LAW - WSWS PROPUBICA -INVESTOPI-CONVERSATION - BALANCE - QUORA - FIREPOWER - GLOBAL- NDTV- ALJAZEER- TASS- DAWN

NHẬN ĐỊNH - QUAN ĐIỂM

See It Through with Nguyen Van Thieu

SEE

IT THROUGH

WITH NGUYEN

VAN

THIEU

THE NIXON

ADMINISTRATION EMBRACES A

DICTATOR, 1969-1974

By JOSHUA K. LOVELL, BA, MA

A Dissertation

Submitted to the

School of

Graduate

Studies in

Partial

Fulfillment of

the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy

McMaster University © Copyright

by Joshua K.

Lovell, June

2013

McMaster University DOCTOR

OF PHILOSOPHY

(2013),

Hamilton, Ontario

(History)

TITLE:

See It

Through with

Nguyen Van

Thieu: The

Nixon

Administration Embraces a Dictator,

1969-1974

AUTHOR:

Joshua K.

Lovell, BA

(University of

Waterloo), MA

(University of

Waterloo) SUPERVISOR: Professor Stephen M. Streeter

NUMBER OF PAGES: ix,

304

ABSTRACT

Antiwar

activists and Congressional doves condemned the Nixon

administration for supporting South Vietnamese President Nguyen

Van Thieu, whom they accused of corruption, cruelty,

authoritarianism, and inefficacy. To date, there has been no

comprehensive analysis

of Nixon’s

decision to

prop up a

client dictator

with seemingly

so few virtues. Joshua Lovell’s dissertation addresses

this gap in the literature, and argues that racism lay at the

root of this policy. While American policymakers were generally

contemptuous of the Vietnamese, they believed that Thieu

partially transcended the alleged limitations of his race. The

White House was relieved to find Thieu, who ushered South

Vietnam into an era of comparative stability after a long cycle

of coups. To US officials, Thieu appeared to be the only leader

capable of planning and implementing crucial political, social,

and economic policies, while opposition groups in Saigon’s

National Assembly squabbled to promote their own narrow

self-interests. Thieu also promoted American-inspired

initiatives, such as Nixon’s controversial Vietnamization

program, even

though many

of them

weakened his

government.

Thieu’s performance

as a national

leader and administrator was dubious, at best, but the Nixon

administration trumpeted his minor achievements and excused his

gravest flaws. Senior policymakers doubted they would find a

better leader than Thieu, and they ridiculed the rest of the

South Vietnamese as fractious, venal, and uncivilized. While the

alliance ultimately chilled over disagreements regarding the

Paris peace negotiations, Washington’s perception of Thieu as a

South Vietnamese superman facilitated a cordial relationship for

most of Nixon’s first term in office.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I owe debts of

gratitude to a wide variety of people, without whom I could not

have completed this dissertation. Professor Stephen M. Streeter

provided much needed guidance as I planned and organized this

project, and offered critical feedback on chapter drafts. Drs.

Jaeyoon Song and Richard Stubbs similarly offered exceptional

advice along the way.

I am

indebted to

my colleagues in

the graduate

program at

McMaster

University, who provided encouragement at various junctures. I

would similarly like to thank Dr.

Andrew

Hunt, from

the University of Waterloo,

for inspiring

my interest

in the

Vietnam War in the first place.

I could not

have conducted my research without the generous assistance of

the staff and archivists at the LBJ Presidential Library, Nixon

Presidential Library and Museum, and National Archives and

Records Administration. They helped me organize my

investigation, and directed me to source material that I would

not have otherwise found.

I also

owe special

thanks also

to “B”

and Gloria

Newell, who

helped me

navigate unfamiliar cities during prolonged visits to

those archives.

I depended very

heavily on my family over the course of this doctoral program.

My parents, Kevin and Robbin Lovell, and brothers, Lucas and

Matthew, urged me to pursue my dream and provided much needed

assistance along the way. My grandparents—Burt and Eileen Lovell

and Ross and Doreen Auliffe—never failed to provide much

appreciated support. My partner and fiancé, Sarah Bornstein,

galvanized my

determination to

complete this

project and

patiently

suffered through

the neuroses

of a busy

graduate student. Finally, I would like to thank Dylan Auliffe

for serving as a

tremendous

source of

inspiration.

Dylan’s life

was unjustly

brief, but

I will

always remember him as a model of courage, strength, and

determination.

TABLE

OF CONTENTS

Chapter 5:

When the

Tail Can’t

Wag the

Dog, 1972–Jan

1973.......................................

237

LIST OF

ABBREVIATIONS

APC:

Accelerated Pacification Campaign ARVN:

Army of

the Republic

of Vietnam

BNDD: Bureau

of Narcotics

and Dangerous

Drugs

CAP:

Code for

Outgoing

Telegram from

the White

House CDST: Camp David Study Table

Chron: Chronological

File

CIA: Central

Intelligence Agency CIP:

Commercial

Import Program

CNR: Committee

of National

Reconciliation

CORDS:

Civil

Operations and

Revolutionary Development Support

COSVN: Central Office for South Vietnam

CR: Congressional

Record

Deptel:

Telegram from

the Department of State Embtel:

Embassy Telegram

FRUS:

Foreign

Relations of

the United

States (series)

FWWR: Files of Walt W. Rostow

GVN:

Government of Vietnam

(used in

some source

material

titles) HAK Telecons: Henry A. Kissinger Telephone Conversations

IAC: Irregular

Affairs Committee IMF:

International

Monetary Fund JCS:

Joint Chiefs of Staff

JUSPAO: Joint

US Public

Affairs Office

LBJLM:

Lyndon Baines

Johnson

Library and

Museum LTTP: Land-to-the-Tiller Program

MACV:

Military

Assistance Command,

Vietnam MP: Memoranda for the President

MPC:

Military

Payment Certificate

MR: Military Region

MTP: Memos to the

President

NARA: National

Archives and

Records

Administration

NCNRC:

National

Council of

National

Reconciliation and

Concord NLF: National Liberation Front

NSC: National

Security Council NSCF:

National Security

Council Files

NSCIF:

National

Security Council

Institutional (“H”) Files NSCMM:

NSC Meeting Minutes

NSDF:

National Social

Democratic

Front NSF: National Security Files

OO: Oval

Office

PAVN:

People’s Army

of Vietnam PC: Presidential Correspondence

PF: Popular

Forces

POF:

President’s Office Files POW:

Prisoner of War

PRG:

People’s

Revolutionary

Government PSDF: People’s Self Defense Force

RG: Record

Group

RVNAF:

Republic of

Vietnam Armed

Forces SMOF: Staff Member and Office Files

TJN: Tom Johnson’s

Notes

TOHAK:

Telegram to

Henry A.

Kissinger US: United States

USAID:

United States

Agency for

International

Development USIA: United States Information Agency

VC:

Viet Cong,

derogatory term for

NLF VCF: Vietnam Country File

VSF: Vietnam

Subject Files WHSF:

White House

Special Files

WHT: White House Tapes

WR:

Walt Rostow

DECLARATION OF

ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT

Joshua Lovell is the

sole author of

this dissertation.

INTRODUCTION

He

was lying

in the

back of

an armored

personnel

carrier. Once

the most

powerful man in the country, Ngo Dinh Diem looked quite

humble on this late-fall morning. He had entered the vehicle

willingly, despite his disappointment that the generals had not

arrived in a limousine. Desperate times required him to

sacrifice some of the conveniences of his office. The personnel

carrier did not offer the safety it promised, though. Once

inside, a disgruntled junior officer shot Diem in the head and

stabbed his brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, repeatedly. Blood splattered

across Diem’s face as his body fell awkwardly, his back bent

forward with his hands tied behind him. He was later granted

an ignoble burial in a prison cemetery. His cause of

death was listed as “suicide,” though the government added the

adjective “accidental” after pictures of the corpse became

public. His death certificate listed him as a province chief,

but he had long since moved beyond this office.

Until 2

November 1963,

Ngo Dinh

Diem had

been the

president of

the Republic of (South) Vietnam.1

Before his

death, the White House had shaped its foreign policy in Vietnam

around the slogan of “sink or swim with Ngo Dinh Diem.”2

In late 1963, however, President

John F.

Kennedy and

his advisers

grew weary

of Saigon’s

incurable instability

![]()

1

Seth Jacobs,

America’s

Miracle Man

in Vietnam:

Ngo Dinh

Diem,

Religion, Race,

and

U.S.

Intervention in Southeast Asia

(Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), 1; Seth

Jacobs, Cold War Mandarin:

Ngo Dinh Diem and the Origins of America’s War in Vietnam,

1950-1963 (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006), 6; Stanley

Karnow, Vietnam: A

History

(New York:

The Viking

Press, 1983),

276. See

also Edward

Miller,

Misalliance: Ngo Dinh Diem, the United States, and the Fate of

South Vietnam (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013).

2

Jacobs,

America’s

Miracle Man

in Vietnam,

2.

and Diem’s

heavy-handed reactions to dissent. With approval from the White

House, a cabal of South Vietnamese generals orchestrated a coup.

General Duong Van Minh, also known as “Big Minh,” seized power

in Saigon, releasing a wave of coups and countercoups that

yielded five different governments between November 1963 and

June 1965. South Vietnam did not achieve a measure of stability

until two young officers took control. A brash air marshal named

Nguyen Cao Ky and an army general named Nguyen Van Thieu

succeeded in stabilizing South Vietnam by late 1966. Both men

had participated in

the coup

that unseated

Ngo Dinh

Diem. Ky

originally

took the

top office

in Saigon, but Thieu surpassed him in 1967 and stepped

into the presidency.3

Kennedy died three weeks after Diem.4 His successor,

Lyndon Baines Johnson, grew

increasingly

frustrated with the

instability in Saigon,

which

threatened to

undermine the anticommunist state. The Johnson

administration never particularly liked any of the South

Vietnamese leaders that

emerged after

Diem’s death,

including

Nguyen Van

Thieu. Johnson, however, did

not remain

in office

long enough

to develop

faith in

his new

client. In 1969, just

a year

after and

a half after

taking the

presidency,

Thieu watched

his greatest

ally of the war walk into the White House. President Richard

Milhous Nixon was dedicated to ending the war on terms Americans

could respect, and he built his Vietnam policy around the

preservation of Thieu.

3 George C. Herring,

America’s Longest War: The United States and Vietnam, 1950- 1975,

Fourth Edition (Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2002), 103-129, 162;

Jacobs, Cold War Mandarin,

1-4; Bui Diem with David Chanoff,

In the Jaws of History

(Bloomington: Indiana

University Press,

1999), 105,

121, 146-147,

171, 207;

George

McTurnan Kahin,

Intervention: How America

Became Involved in Vietnam (New York: Alfred A. Knopf,

1986), 195; Nguyen Cao Ky with Marvin J. Wolf,

Buddha’s Child: My Fight

to Save Vietnam (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2002), 91-99.

4

Herring,

America’s

Longest War,

127-129.

Washington’s

decision to

prop up this

particular dictator was

guided by

a complex

array of factors that shaped the entire US intervention. Hoping

to contain Chinese and Soviet influence, the White House sought

a fierce anti-communist who could serve as a bulwark for

Western—specifically, American—power. Hoping to protect the

American empire, and make it more sustainable, the Nixon

administration needed a leader who could maintain the stability

of South Vietnam while Washington reduced its

commitments to the country. Nixon fancied himself a

realist, who need not interfere with the internal policies of

his allies unless it suited US interests. He therefore sought to

reduce some of the burdens Washington bore in its pursuit and

preservation of empire.

This

realignment of priorities forced the White House to rely on a

strongman who could preserve

order, even

to the

detriment of

the US

mission to

protect South

Vietnamese

self- determination. As an adept political leader who enjoyed

the backing of the South Vietnamese

military,

Thieu appeared

to be

the best

candidate.5

Nixon also

credited Thieu

with facilitating the Republican Party’s victory in the 1968 US

presidential elections. By undermining Johnson’s efforts to

reach a peace settlement, Thieu had hampered the campaign of the

Democratic candidate, Vice President Hubert Humphrey.

5

Melvin Small, The

Presidency of Richard Nixon (Kansas: University Press of

Kansas, 1999), 60-‐61;

Michael Latham,

The

Right Kind

of Revolution:

Modernization, Development, and U.S. Foreign Policy from the

Cold War to the Present (Ithaca: Cornell University Press,

2011), 142;

John L. Linantud, “Pressure and Protection: Cold War

Geopolitics and Nation-Building in South Korea, South Vietnam,

Philippines, and Thailand,”

Geopolitics 13,

no. 4

(November 2008): 635-656,

p. 647;

Robert J.

McMahon, The Limits

of Empire: The United States and Southeast Asia Since World War

II (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 157; Gabriel

Kolko, Anatomy of a War:

Vietnam, the United States, and the Modern Historical Experience

(New York: Pantheon Books, 1985), 208-216

Finally,

Washington backed Thieu because US officials did not think that

anyone else could serve as a suitable replacement. American

support for Thieu was based less on a belief that he was a

perfect client—though the Nixon administration was generally

pleased with

his

performance—than that

strong

leadership seemed to

be in

short supply

in South Vietnam. Their experiences in Vietnam up to 1969

had left American officials disenchanted with Saigon’s political

and military leadership. The White House’s support for Thieu was

therefore partly based on the racist assumption that all other

Vietnamese were irrational, fractious, selfish, and incompetent.

Nixon

administration officials would have likely denied that they were

racist in the same fashion as, say, pre-Civil War slave owners.

To apply historian Seth Jacobs’ phrase,

racism in

the Nixon

administration

was “historically

specific.” Few policymakers in the

White House described the Vietnamese as a “distinct genetic

group," but US officials believed that their allies embodied

certain character flaws that made them inferior. Usually, those

officials blamed these weaknesses on Vietnamese culture and

history. As such, it might be better to describe American

prejudices as “ethnocentrism.” As Jacobs notes, though,

ethnocentrism is “a word academics employ to avoid saying what

they mean.” The virulence of American prejudices toward the

Vietnamese is better conveyed with a term like “racism.”6

![]()

Indeed, there are good

reasons to

treat

prejudices regarding biology

and culture

as conceptually identical. In both cases, elements of one

society consider themselves superior to another, and attribute

this hierarchy to some innate shortcoming in their

6

Seth Jacobs,

The

Universe

Unraveling: American Foreign

Policy in

Cold War

Laos

(Ithaca: Cornell

University Press, 2012),

7-14.

counterparts.

These flaws are social inventions, without the backing of

scientific evidence.

Throughout the Cold

War, American

policymakers condemned foreigners

as comparatively weak, irrational, mercurial, corrupt,

and primitive. These perceived differences helped Americans

justify extraordinary measures in conflicts abroad, particularly

the employment of violence. It did not really matter whether

Washington considered a given community biologically or

culturally deficient, because the results were the same either

way.7

Nixon’s

personal views on race were complex, and sometimes inconsistent.

His successful electoral campaign in 1968 was based largely on a

policy of courting white Southern racists who were angry with

the black Civil Rights Movement. Before his presidential

campaign,

however, Nixon

had actually

been one

of the

Republican Party’s greatest supporters of civil rights. As Dwight D.

Eisenhower’s vice president, Nixon

7

Gerald

Horne, “Race

to Insight:

The United

States and

the World,

White Supremacy

and Foreign Affairs” in

Explaining the History of

American Foreign Relations, 2nd ed. edited by

Michael J. Hogan and Thomas G. Paterson (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 2004): 323-335; Douglas Little,

American Orientalism: The

United States and the Middle East since 1945, 3rd

ed. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 3;

Thomas Borstelmannn, The

Cold War and the Color Line: American Race Relations in the

Global Arena (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001),

6-7; Mary A. Renda, Taking

Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of U.S. Imperialism,

1915-1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press,

2001), 301-397; Stuart Anderson,

Race and Rapprochement:

Anglo-Saxonism and Anglo-American Relations, 1895-1904

(Toronto et al: Associated University Presses, 1981);

Michael H. Hunt,

Ideology and U.S.

Foreign Policy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987),

176-177; Michael L. Krenn,

The Color of Empire: Race and American Foreign Relations

(Washington, DC: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006); Jacobs,

America’s Miracle Man in

Vietnam, 14-15; Alana Lentin, “Replacing ‘race,’

historicizing ‘culture’ in multiculturalism,”

Patterns of Prejudice

39, no. 4 (December 2005):

379-396; David

Brion Davis, “Constructing Race: A Reflection,”

The William and Mary

Quarterly 54, no. 1 (January 1997): 7-18; John Solomos and

Les Back, “Conceptualising Racisms: Social Theory, Politics and

Research,” Sociology

28, no. 1 (February 1994): 143-161.

helped defeat a

Senate filibuster threatening civil rights legislation. He also

traveled to Ghana as Washington’s representative at a ceremony

commemorating that country’s independence, and was appointed an

honorary member of the National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People in recognition of his support for black

Americans. Senator

Barry Goldwater

(R-AZ) claimed

that Nixon’s

efforts to

impress

Southern racists in

1968 were simply shrewd politicking, or “hunting where the ducks

are.”8

As

president, however, Nixon

left a

long record

of racism.

He referred

to blacks

as “niggers” and “jungle bunnies.”

When he was

informed about a

new educational program for black students, he responded,

“Well it’s a good thing. They’re just down out of the trees.”

The president was also an ardent anti-Semite, believing that

Jewish Americans prioritized Israeli interests over their own

patriotic duties. Once, after Nixon’s Jewish national security

adviser, Henry Kissinger, wrapped up a Cabinet briefing on the

Middle East, the president asked, “Now, can we get an American

point of view?”9 Kissinger, astonishingly, helped

sustain the president’s anti-Semitism. During a discussion on

relations with Moscow, Kissinger stated that, “if they put Jews

into gas chambers in the Soviet Union, it is not an American

concern. Maybe a humanitarian concern.” Nixon could not have

agreed more: “We can’t blow up the world because of it.”10

Nixon’s

prejudices were linked to faulty assumptions about both biology

and culture. He

claimed on

numerous

occasions that blacks

were

genetically inferior

to their

![]()

8

Borstelmannn,

The

Cold War

and the Color

Line, 223-225.

9 Ibid,

226-227.

10

Adam

Nagourney, “In

tapes, Nixon

Rails About

Jews and

Blacks,”

New York Times,

10 December 2012.

white

counterparts.11 He linked this alleged biological

difference to the slave trade. Secretary of State William Rogers

believed that blacks could strengthen the country, Nixon once

explained to his assistant, Rose Mary Woods. Rogers’ belief was

“a decent feeling,” Nixon declared, but blacks would need five

hundred years to become strong. “What has to happen,” Nixon

said, “is they have to be, frankly, inbred.” Nixon did not

restrict his prejudices to the descendants of slaves. Indeed, he

argued in February 1973 that,

“I’ve just

recognized that, you

know, all

people have

certain

traits.” For

example, the

“Irish can’t drink. What you always have to remember with the

Irish is they get mean.

Virtually

every Irish

I’ve known

gets mean

when he

drinks.

Particularly the

real Irish.”

Of course, the Irish were not the worst of the European

lot to Nixon’s mind. “The Italians, of course, those people…

don’t have their heads screwed on tight.”12

Nixon

was not

the only

member of

his administration to

harbor such

prejudices.

When Roger

Morris, a member of the National Security Council (NSC),

prepared to present a briefing on African issues, he noted that

General Alexander Haig, Kissinger’s deputy, “would begin to beat

his hands on the table, as if he were pounding a tom-tom.”

Morris also heard numerous comments about apes and smells, which

seem to have pervaded the White House. On his way to a dinner

for African ambassadors, one night, Kissinger

asked Senator

J. William

Fulbright, “I wonder

what the

dining room

is going to smell like?”13

![]()

11

Borstelmannn, The

Cold War and

the Color Line, 226-227.

12

Nagourney, “In

tapes, Nixon

Rails About

Jews and

Blacks.”

13

Borstelmannn,

The

Cold War and

the Color

Line,

228.

The Nixon

administration’s condemnations of the Vietnamese were usually,

though not

always, framed

in terms

of culture.

American

policymakers lamented

that the

Vietnamese were too suspicious or manipulative for their own

good. The Vietnamese allegedly developed these traits because

evasiveness allowed them to survive their long history of

fighting off powerful foreign invaders. Washington also

criticized the South Vietnamese for allowing their vanity or

selfish desires to override political pragmatism. As Saigon’s

policymaking elites debated major national policies, US

officials vented about an inherent Vietnamese predisposition

toward factionalism that stalled critical wartime programs.

Worse still, the Vietnamese seemed incapable of implementing

policies efficiently or effectively, even when they could reach

a consensus.

American

officials sometimes framed their criticisms in gendered

language, but such discourses were rooted in racism. Senior

policymakers scoffed at Vietnamese caution in military campaigns

or the peace process, and suggested that Washington’s allies

needed to act with greater confidence, strength, or other

stereotypically masculine traits.

Similarly, US

officials

sometimes took it

upon

themselves to

offer guidance

to the

Vietnamese, using language reminiscent of father-child

relationships. In these cases, Washington policymakers portrayed

the Vietnamese as immature, instead of feminine, men. The

White House

also made war

plans without consulting its allies, which in some cases suggested that the

Vietnamese were too childish to be trusted with their own

defense.

While important

on their

own, these

gendered

discourses emerged

within a

much broader and more detailed dialogue regarding South

Vietnamese racial inferiority.14

The White

House’s prejudices toward the Vietnamese reflected popular

opinions. In 1969, the media discovered that American soldiers

had slaughtered innocent civilians in the Vietnamese village of

My Lai. The military covered up this story for over a year, but

laid charges against Lieutenant William J. Calley for murdering

seventy “Oriental human beings” after news of the massacre

broke. The American public was more concerned about US soldiers

than foreign victims, and many assumed that Vietnam was causing

the kind

of moral

decline that

resulted in

the My Lai

Massacre. Many Americans,

including Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter, portrayed Calley as a

scapegoat. After Calley was sentenced, Carter asked Georgians to

keep their headlights on when they drove, in order to “honor the

flag” as Calley had. Some soldiers who had been honorably

discharged gasped in disbelief at Calley’s trial. “The people

back in the world don’t understand this war,” one soldier said.

“We are here to kill dinks. How can they convict Calley for

killing dinks? That’s our job.”15 Even if they were

not involved directly in criminal slaughter, many Americans

referred to the Vietnamese as “gooks” or “slopes.”16

14 The role of gender in US foreign relations has been

well established. See, for example: Robert D. Dean,

Imperial Brotherhood: Gender and the Making of Cold War Foreign Policy

(Amherst: University of

Massachusetts Press, 2001);

Geoffrey F.

Smith,

“Security, Gender, and the Historical Process,”

Diplomatic History 18,

no. 1 (January 1994): 79-90; Robert A. Nye, “Review Essay:

Western Masculinities in War and Peace,”

American Historical

Review

112, no.

2 (April

2007): 417-38;

and Cynthia

Enloe,

Bananas, Beaches & Bases:

Making Feminist Sense of International Politics (Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1990).

15 Ibid,

229-230.

16

Hunt, Ideology

and U.S.

Foreign Policy,

176-177.

Despite

these

prejudices, there

was at

least one

Vietnamese

leader who

earned the

Nixon administration’s respect. After Ngo Dinh Diem’s death,

South Vietnam was consumed by political turmoil. By 1967,

however, Nguyen Van Thieu emerged as the undisputed leader of

the country. The South Vietnamese president quelled the national

turbulence, and seemed both capable and willing to implement

American policy advice. The White House praised Thieu for being

pragmatic, reasonable, and energetic, while condemning South

Vietnamese opposition leaders for absurd obstructionism. Thieu

had many flaws, and US officials easily identified them. Nixon

and his advisers frequently expressed

frustration

with Thieu’s

slow, cautious

approach to

political

reforms. They

also noted that Thieu seemed to share an alleged

Vietnamese obsession with prestige and status. As such, he could

not promote policies unless the public believed that he was

acting on his own volition, free of American pressure. Thieu

also worried about the very significant opposition he faced over

controversial policies like austerity taxes and American troop

withdrawals. He was therefore slow to implement such policies.

Seth Jacobs

argues that Ngo Dinh Diem had faced similar prejudices from US

officials, but his Catholicism and capacity to transcend the

perceived limitations of his race allowed him to maintain

American support. The White House rationalized Diem’s

authoritarianism and

brutality as products

of an

inferior Asian

culture, but

praised him

for taking a strong pro-Western stance in a country where

communism and neutralism were both popular.17 Several

years later, Thieu benefited from a similar dynamic. American

officials believed that, while Thieu was too cautious, he was

still a more effective leader

![]()

17

Jacobs,

America’s

Miracle Man

in Vietnam, 11-16.

than

any of

his

predecessors since

Diem. If

he was

an oppressive tyrant, it

was because

he was a traditional mandarin in a nation wracked by

discord. If he sometimes acted unwisely, he was far more

reasonable than South Vietnamese civilian leaders, communists,

or neutralists. An American might have been bolder, smarter, and

more effective, but Americans could not govern in Saigon. The

White House believed that Thieu manifested the perceived

character flaws of his race, but he could also break past

them.

Vietnamese

stereotypes seemed to explain the weaknesses of Saigon’s

political leaders. Such prejudices could also serve as a moral

salve, when a realism-driven White House sustained support for a

tyrannical and authoritarian regime in Saigon. Indeed, the high

frequency with which US officials referenced alleged South

Vietnamese character and

cultural flaws

suggests that

they were

convincing themselves of

the

righteousness of

their actions. The Nixon administration’s racism therefore

constituted not only a set of faulty assumptions that skewed

evaluations of the Vietnamese, but also a process of justifying

American actions in Vietnam over the protests of external

figures and individual consciences.18

![]()

18

This

process has

been observed

in other

arenas. Edward

Said, for

example,

argues that prejudices regarding

Asians have

justified

efforts to

dominate and

re-‐order

societies in the region. Racism is thus a critical

component of empire. See Edward Said,

Orientalism (New York:

Vintage Books, 1979), 3. Similarly, Tami Davis Biddle argues

that decision makers tend to discount the drawbacks of certain

options, in order to make repugnant choices more palatable. When

these choices are particularly off-‐putting, decision makers raise cognitive barriers that

make reconsideration more difficult. See Tami Davis Biddle,

Rhetoric and Reality in

Air Warfare: The

Evolution of

British and

American Ideas

about

Strategic Bombing,

1914- 1945

(Princeton: Princeton University

Press, 2002),

4-‐6

Despite the

great effort exerted by the White House to support the South

Vietnamese president, accounts of the Nixon-Thieu relationship

remain limited largely because the requisite archival material

was only recently declassified. While there have been few

scholarly inquiries into this relationship, Thieu has not been

completely left out of the story of the Vietnam War. Political

scientist Larry Berman explores Thieu’s perspectives

on the

peace process

in

No Peace,

No Honor.

Nguyen Tien

Hung and

Jerrold Schecter do the same in

The Palace File, an

exceptional work crafted without the benefit of Nixon’s national

security files. Stanley Karnow briefly explains Thieu’s wartime

roles in Vietnam: A

History, as does Gabriel Kolko in his magisterial survey,

Anatomy of a War.

Howard B. Schaffer, a former US diplomat, describes the American

ambassador’s relationship with Thieu in

Ellsworth Bunker.

Schaffer demonstrates that Bunker was unjustifiably

accommodating of Saigon’s strongman, but the author’s focus on

the embassy prevents him from conducting a comprehensive

analysis of opinions of Thieu in the White House. Jeffrey

Kimball argues in Nixon’s

Vietnam War that Nixon bolstered

the Saigon regime because it was stable, and because

Thieu could potentially embarrass his counterpart over a

Republican plot to derail the 1968 peace negotiations. Kimball’s

book is

limited by

his focus on

broader

wartime strategy.

As such,

he does

not explore

the full dynamics of the Nixon-Thieu alliance.19

Other historians comment on Thieu over the course of their

narratives, but they do not address his role in great detail.20

19

Larry

Berman,

No

Peace, No

Honor: Nixon,

Kissinger, and

Betrayal in

Vietnam

(New York: The Free Press, 2001); Kolko,

Anatomy of a War,

especially 208-222; Karnow,

Vietnam;

Jeffrey

Kimball,

Nixon’s Vietnam

War

(Lawrence: University Press of

Kansas, 1998), 87-91; Nguyen Tien Hung and Jerrold R.

Schecter, The Palace File

(New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1986); Howard B.

Schaffer, Ellsworth

Bunker: Global

There is as yet

no scholarly work dedicated specifically to Nixon’s relationship

with Nguyen Van Thieu. This dissertation is designed to help

fill that gap. It is based on American sources alone, and

therefore does not amplify significantly on Thieu’s perspectives

on the

war or

his allies.

Such a study would

no doubt

be useful,

and scholars

should look forward to the day when the relevant Vietnamese

archival records become available. This dissertation nonetheless

contributes to the field by addressing a major question about

American foreign policy. One of the most important decisions

hegemons make in proxy wars is the choice of a client. The US

media and public regarded Thieu with contempt, so the Nixon

administration’s support for him is puzzling. Surely, there must

have been alternative candidates for the presidency of South

Vietnam.

While such

figures may have existed, the Nixon administration never devoted

significant attention

to them.

Convinced that

most South

Vietnamese

were selfish,

venal, corrupt, and ineffective,

the most

important US policymakers

were largely

satisfied with Thieu’s performance. He was friendly and cooperative, in

sharp contrast to some of his predecessors,

and he was at

least

partially successful

at achieving

his major

policy goals.

Some of his efforts, such as his land and economic reforms, did

not actually resolve

![]()

Troubleshooter,

Vietnam Hawk

(Chapel Hill:

University of

North Carolina

Press, 2003),

160-259.

20 See, for example: Francis Fitzgerald,

Fire in the Lake: The

Vietnamese and the Americans in Vietnam (Toronto: Little,

Brown and Company, 1972); C.L. Sulzberger,

The World and Richard

Nixon (New York: Prentice Hall Press, 1987); Marilyn Young,

The Vietnam Wars, 1945-1990 (New York: HarperCollins Publishers,

1991); George C. Herring,

LBJ and Vietnam: A Different Kind of War (Austin: University

of Texas Press, 1994); Robert D. Schulzinger,

A Time for War: The United

States and Vietnam, 1941- 1975

(Oxford:

Oxford University

Press, 1997);

Small,

The Presidency

of Richard

Nixon; Robert Dallek,

Nixon and Kissinger:

Partners in Power (New York: HarperCollins Publishers,

2007).

Saigon’s

problems. American perceptions of his successes, however, seem

more important than

the actual

outcomes of

his policies.

Whenever he

managed to

force a

bill past his political opposition, Thieu strengthened

his reputation in the White House as a strong leader. The

negative consequences of some of those new laws for the South

Vietnamese public did not necessarily tarnish the Nixon-Thieu

relationship.

Nixon’s

predecessor, Lyndon Baines Johnson, occupied the White House

while Thieu rose to power in Saigon. Taking office just after

Diem’s assassination, the Johnson administration grew

disappointed with the series of South Vietnamese governments

that emerged between late 1963 and mid-1965. Ineffective and

fragile, these regimes were neither capable of defeating their

enemies nor stymieing internal conflict. When Nguyen Cao Ky

emerged as prime minister, he settled much of the conflict among

Saigon’s military brass. The Johnson administration did not

particularly respect him, either, though. He

was prone

to making

outrageous statements, and

failed to

fulfill his

promise to

initiate a grand social

revolution to improve

the lives of his

people. When Thieu ascended to the presidency in 1967, he also

failed to win Johnson’s respect. His feud with Ky for the top

office and his lethargic response to a military crisis in 1968

reinforced American assumptions that the Vietnamese were selfish

and incapable of promoting their own

interests.

When Johnson

pushed for a peace agreement in late 1968, however, he realized

that Thieu was a

stronger force than

the White

House had

previously understood. Saigon successfully blocked the peace

initiative, which helped propel Richard Nixon into the White

House. The

Nixon campaign

may have

tried to

encourage Thieu along

this path.

If

Johnson’s peace

initiative failed, Nixon’s odds of winning the US presidential

election would be greatly increased. Working through an envoy

named Anna Chennault, Nixon promised Thieu that the Republicans

would be far friendlier to Saigon than the Democrats. Thieu had

his own reasons to obstruct the 1968 peace deal, and there is

little evidence that Chennault had significant influence over

Saigon. Since the negotiations stalled, however, Nixon felt

indebted to Thieu, and perhaps wary that Saigon would release

details of

the

Republicans’ skullduggery. When

Nixon took

office, he

intended to

reward Thieu’s apparent cooperation in the Anna Chennault

Affair.

![]()

In 1969, therefore, President Nixon devoted his administration

to a policy of rapprochement with Thieu. The new team in the

White House was generally more satisfied with Saigon’s

performance than the Democrats had been. Thieu’s friendly

cooperation with Washington earned him significant goodwill, as

did his willingness to promote

economic

reforms, Nixon’s

Vietnamization

strategy, a reinvigorated

pacification campaign, a new land reform initiative, and

a negotiations strategy that aligned with Nixon’s call for an

“honorable peace.”21 These policies were not always

successful, but American racism helped protect Thieu’s

reputation. Officials in the White House and Embassy Saigon

praised Thieu when he overcame domestic opposition to implement

a desired program, and treated him like a South Vietnamese

superman. By comparison, when Thieu was unable to defeat his

domestic opponents, senior US policymakers condemned

the fractious National Assembly

and junior

South

Vietnamese

bureaucrats for alleged venality and ineptitude.

21

Nixon used

the phrase

“honorable peace” at

the very

outset of

his presidency, in

January 1969. Berman, No

Peace, No Honor, 5.

Sometimes,

Thieu opposed

US-inspired

programs instead

of promoting them. The US

ambassador to Saigon, Ellsworth Bunker, was disappointed with

Thieu’s failure to broaden his base of domestic support by

creating an alliance of political parties and making his Cabinet

more socially diverse. Bunker held many of the same prejudices

as his colleagues in Washington, however, and remained mostly

pleased with Thieu’s performance. Nixon was a devotee of

realpolitik, the principle that national interests should take

priority over all other considerations. He did not believe that

interfering in South Vietnam’s internal affairs was in America’s

interest, nor did National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger.

Nixon centralized the decision-making process for Vietnam

policies in the Oval Office and NSC, so his opinion and

Kissinger’s mattered more than those of other senior

policymakers. Since neither Nixon nor Kissinger cared very much

about the failed nation-building programs, Thieu maintained his

reputation in the White House as a superior South Vietnamese

leader.

The dynamics

that characterized the Nixon-Thieu relationship in 1969

persisted into the

next year,

but the

strategic

environment in Vietnam

turned grim.

Thieu

continued to deliver policy successes in 1970. He implemented

austerity measures, despite continued domestic

opposition, and maintained his support

for US troop withdrawals. He also succeeded in passing

legislation for the Land-to-the-Tiller Program, a land reform

project designed to build public support for the government.

These efforts infuriated Thieu’s domestic opposition, however,

which was already upset at his heavy-handed repression of

dissidents and protection of corrupt officials. The political

stability that Thieu had maintained for years seemed to be

unraveling. After a joint US-South

Vietnamese

invasion of

Cambodia

yielded uninspiring

results, the

White House

began to doubt

that it could win the war through military pressure alone.

Worried that

Saigon’s strength was waning, and that the loss of South Vietnam

would seriously jeopardize American credibility as a global

power, Nixon and Kissinger began to contemplate a grand betrayal

of Thieu. Under this scheme, Washington would provide just

enough aid to allow its client to survive for a few years after

all US troops had left Vietnam. If Saigon fell to the communists

after a “decent interval,” Nixon could not be held responsible.

Scholars have engaged in a vigorous debate about whether or how

relentlessly Nixon pursued the decent interval strategy. The

consequences for the Nixon-Thieu relationship, however, would

have been the same regardless of the White House’s

decision. Nixon decided

in late

1970 to

reaffirm and

enhance his

commitment to

Nguyen Van

Thieu, either

because he

needed a

strongman in

Saigon to

maintain

stability for a decent interval, or because he wanted to

preserve a permanent government in a tumultuous war zone.

In 1971,

therefore, the Nixon administration attempted to further

strengthen the Thieu regime. Washington provided American assets

to assist Thieu’s campaign during the South Vietnamese

presidential election. Nixon even modified the schedule of

American troop

withdrawals, so that

South

Vietnamese voters

would feel

safe on

Election Day. Officials in both Washington and the US

embassy in Saigon protested when Thieu drove his competition out

of the contest, but they rallied to his side when he

orchestrated a one-man

election. If ever the Nixon administration had an opportunity to

replace Thieu with someone else, the 1971 election was it.

American officials never gave any serious

thought

to such

a plan

because they

were convinced

that all

of the

other

candidates were weak,

incompetent, and misguided. Even as the Nixon administration

worried that its client state was collapsing, Thieu maintained

his status as an exceptional South Vietnamese specimen.

Thieu’s

re-election did not

convince Nixon

that he

no longer

needed to

consider a

decent interval strategy. Other efforts to strengthen the Thieu

regime failed, though US officials hoped that the South

Vietnamese president could reinvigorate some of these programs

after he secured a second term in office. Nixon’s War on Drugs,

for example, was designed in part to repair Thieu’s reputation

at home and abroad. Widely considered corrupt, and accused of

participating in the drug trade, Thieu needed to improve his

public image.

His regime

was built

on a

pyramid of

corruption,

however, where

tolerance for certain criminal practices allowed junior

officials to secure the patronage of their superiors.

Thieu could

not attack

narcotics traffickers without

compromising many of

the people who owed him allegiance. Pacification, which

was relegated to lower echelons of both the South Vietnamese and

American governments in 1971, floundered as well.

Finally, North

Vietnamese soldiers routed their Southern counterparts when the

latter invaded Laos. While Thieu promoted the White House’s

claim that the invasion was a tremendous success, Nixon and

Kissinger were still deeply troubled about the prospects of

achieving peace with honor. They continued to mull over a

potential decent interval solution.

While Thieu

discerned some

of the

details of

the American

negotiating

strategy, he did not yet know the full extent of Nixon’s

scheming.

Despite the new

tensions developing in the Nixon-Thieu relationship, the

alliance remained strong through the first part of 1972. When

Hanoi launched the Spring Offensive, an ambitious invasion of

the South, Washington came to Saigon’s aid. Thieu’s performance

as a leader was far more impressive this time than during the

1968 Tet Offensive, though he still lost some territory to the

enemy. The Spring Offensive also convinced Washington and Hanoi

that it was time to earnestly pursue a peace settlement,

however, which was finally signed in January 1973. Thieu

vehemently opposed this settlement because it put his government

at political and military disadvantages. The Nixon

administration was baffled by this resistance, and promised

Thieu he would have the full support of the

United States if Hanoi

violated a peace treaty. When

such promises failed to bring Thieu along, US officials voiced

their prejudices toward the

Vietnamese in

brutal, virulent terms.

No longer

convinced that Thieu

was a

South

Vietnamese superman,

Nixon and Kissinger lashed out with threats and insults.

Eventually, Thieu conceded defeat, but the American alliance

with Saigon had been shattered and South Vietnamese security was

fatally compromised.

While the US

intervention was finally over, the Paris Peace Accords did not

settle the war for the Vietnamese. Both parties violated the

ceasefire, and Hanoi finally secured victory with the Ho Chi

Minh Offensive of 1975. Nixon met Thieu in San Clemente,

California, shortly

after the

Accords were

signed. The

US president renewed his

pledge to

retaliate against communist ceasefire violations, but he never

again sent American soldiers to Vietnam. Soon distracted by the

Watergate scandal, Nixon devoted less attention to Saigon.

Gerald R. Ford replaced Nixon as president, when the latter was

forced to

resign in disgrace. Ford lacked the political capital necessary

to overcome Congressional

and public

opposition to

a renewed

commitment to Vietnam,

and he

never met with Thieu. The South Vietnamese president fled

Saigon just before the city fell to the communists. The American

war in Vietnam was finally over.

Nixon did not

fight the Vietnam War simply because he was racist, and there

were certainly elements of realpolitik in his sustained support

for a dictatorial client. American prejudices, however, helped

the White House choose Thieu over potential alternatives.

Officials in the White House and Embassy Saigon believed that

the Vietnamese were innately inferior to Americans. Nixon and

his advisers complained bitterly throughout the war about

Vietnamese factionalism, incompetence, and venality. Thieu did

not conform perfectly to this stereotype, and so convinced

Americans that he had transcended his racial weaknesses. At the

same time, the Nixon administration’s bigotry protected Thieu

from criticism regarding his brutal repression, tolerance of

corruption, and electioneering. He may have been an exceptional

leader, US officials thought,

but he

was still

Vietnamese. He could

not escape

his basic

nature. Even

when the

Vietnam War seemed to turn against the allies, and Nixon was

forced to consider a terrible betrayal, Washington held on to

Nguyen Van Thieu. Poor performance and brutality could not

tarnish the reputation of Saigon’s superman. The Nixon-Thieu

relationship was only dissolved when American and South

Vietnamese national interests clashed directly.

CHAPTER

1: THE RISE OF

NGUYEN VAN

THIEU, 1964-1968

When Lyndon

Baines Johnson took over the

US presidency, he

faced a

precarious strategic environment in South Vietnam. America’s

strongman in Saigon, Ngo Dinh Diem, fell to assassins three

weeks prior to John F. Kennedy’s tragic

death. Over the next year and a half, the fledgling nation was wracked by

instability, falling under the sway of no

fewer than

five different

governments.

As the

Republic of

Vietnam

struggled to fill

the power vacuum Diem left, it suffered debilitating

losses to the insurgents of the National Liberation Front (NLF).

Described derisively by their enemies as Viet Cong (VC), for

Vietnamese communists, the Front comprised a diverse group of

nationalists seeking to overthrow the government in Saigon.1

The NLF’s

achievements in the field put the survival of South Vietnam at

risk, and it was not until 1965 that leaders strong enough to

hold the South together seized power. Even then, the Johnson

administration expressed frustration with the South Vietnamese

government. American officials assumed that South Vietnam was

incapable of rational political development, so they instead

focused on finding a leader who would maintain stability. Nguyen

Van Thieu eventually emerged to fulfill this role, but he too

failed to earn

Johnson’s

respect. While

Richard Nixon

later embraced

Thieu as

a superior

national leader, the Johnson administration considered Saigon’s

new strongman just another manifestation of South Vietnamese

backwardness. Thieu was stronger than the Johnson

administration

expected, though,

as he

demonstrated by

derailing the

1968 peace

process. An ardent

nationalist, Thieu refused

to negotiate

in good

faith with

the North

![]()

1

Herring,

America’s

Longest War, 127, 133,

140, 151-152, 162.

Vietnamese

and NLF.

Never

satisfied with

his client

in South

Vietnam,

Lyndon Johnson now

lacked the power to force Thieu’s compliance with American

policies.

Racism was not

the sole cause of the Johnson administration’s frustrations with

Saigon. The South Vietnamese government was weak and too focused

on internal political

challenges to

fight its

enemies

effectively. As such,

there were

perfectly

rational reasons for the White House to express frustration with

its client. The Johnson administration’s prejudices exacerbated

those tensions,

though, and seemingly explained Saigon’s political instability.

After complaining that South Vietnamese civilization was weak

and under-developed, the White House abandoned its lofty goals

for a democratic, civilian government in Saigon, and instead

relied on dictators who could maintain order.

LYNDON

JOHNSON’S VIETNAM WAR

Johnson’s

predecessor, John F.

Kennedy, was

an ardent Cold

War hawk

who had tried

to arrest the spread of communism by offering economic and

military assistance to modernize the Third World. American

officials believed that developing countries were “primitive”

and “childlike,” compared to the “advanced” West, and thus

vulnerable to communist subversion. According to Kennedy adviser

Walt Rostow, as primitive societies evolved toward more advanced

economic models, “individual men are torn between the commitment

to the old familiar way of life and the attractions of a modern

way of life.” Rostow argued that communists took advantage of

such instabilities to pervert the modernization process.

Kennedy’s foreign aid programs were therefore

designed

to protect

countries like

Vietnam from

communist

subversion by accelerating their

evolution toward Americanized capitalism.2

Lyndon Johnson

shared many of Rostow’s views of the developing world, and

followed his predecessor’s commitment to nation building as a

defense against communism. With a hyper-masculine desire to

stand up to the communist “bully,” Johnson wanted to uplift

“young and unsophisticated nations” from the torments of

“hunger, ignorance, poverty, and disease.”3 To

Johnson’s mind, Vietnam fell perfectly within that rubric of

unsophisticated countries. He once referred to North Vietnam as

a “raggedy-ass, little fourth-rate country.”4 He was

no more generous with the South Vietnamese, whom Johnson

regarded as

primitive,

fractious, and completely

irrational.5

While Johnson

phrased his goals for the Third World in altruistic terms of

protection and development, he never lost sight of his ultimate

goal: containing communism.

As such, he

did not

always apply

American

democratic models in

Vietnam. Johnson’s focus on the Cold War competition led

him to diverge from Kennedy’s policy

![]()

2 Stephen M. Streeter, “The US-Led Globalization

Project in the Third World: The Struggle for Hearts and Minds in

Guatemala and Vietnam in the 1960s,” in

Empires and Autonomy:

Moments in

the History

of

Globalization,

edited by

Stephen M.

Streeter,

John

C. Weaver,

and William

D. Coleman,

196-211

(Vancouver: UBC

Press, 2009),

196-199. See also, Latham,

The Right Kind of

Revolution; David Ekbladh,

The Great American

Mission: Modernization and the Construction of an American World

Order (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010); and

David Engerman et al (ed.),

Staging Growth:

Modernization, Development, and the Global Cold War (Boston:

University of Massachusetts Press, 2003).

3

Michael

Hunt,

Lyndon

Johnson’s War:

America’s Cold

War Crusade

in Vietnam,

1945- 1968 (New York: Hill and Wang, 1996), 75-76.

See also Dean, Imperial

Brotherhood, 201-240.

4

Hunt, Lyndon

Johnson’s War, 104-105.

5 Robert Dallek,

Flawed

Giant: Lyndon

Johnson and

His Times, 1961-1973

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 243.

in two

important ways. First, whereas Kennedy hesitated to adopt a

significant combat role in Vietnam, Johnson accepted such a

sacrifice as a necessary condition for victory. Second, Johnson

was more devoted to maintaining order when nation-building

projects floundered.

He thus

fervently

opposed Kennedy’s

guidance of

the November

1963 coup in

Saigon. Ngo Dinh Diem had been a brutal dictator with limited

popular support, but Johnson credited him with stabilizing South

Vietnam. During a visit to that country in 1961, Johnson even

compared Diem to a heroic Winston Churchill.6

![]()

The Johnson administration was never completely comfortable with

any of the five South

Vietnamese governments that emerged after Diem’s death.

Evaluating these regimes through the prisms of their personal

prejudices, US officials concluded that the Vietnamese were

neither efficient nor competent. Two senior South Vietnamese

military officers, Nguyen Cao Ky and Nguyen Van Thieu, finally

ended the cycle of coups and countercoups in 1965, but Saigon

continued to face dramatic political and military crises through

1968. The tenuous stability that emerged in South Vietnam,

moreover, cost Johnson his nation-building project. As the

generals in Saigon’s Independence Palace competed with each

other for power, they failed to implement the policies that

Johnson believed would strengthen Saigon’s claim to sovereignty.

South Vietnam finally achieved a stable government just as the

Johnson administration collapsed. The US president tried to

negotiate a peace

agreement

before the

end of

his term,

but Thieu

thwarted him.

Saigon then saw a new, seemingly friendlier ally step

into the White House, in the form of Richard Nixon.

6 Hunt,

Lyndon

Johnson’s War,

75-79; Lloyd

C. Gardner,

Pay

any Price:

Lyndon Johnson and the Wars for Vietnam (Chicago:

Ivan R. Dee, 1995), 52-54.

YOUNG

TURKS

In the fall of

1964, South Vietnam was still struggling to fill the power

vacuum that Ngo Dinh Diem’s death had created, but a group of

young military officers was emerging as a strong political

force. Chief among these Young Turks was a thirty-five year old

air marshal named Nguyen Cao Ky. He had the support of another

rising star: forty-two

year old

army General

Nguyen Van

Thieu. The

Young Turks

were ambitious,

and sought additional power and authority. They lobbied their

embattled junta leader, Nguyen Khanh, to make room for fresh

military leadership by firing several senior

generals.7

Khanh was a

career soldier, not the kind of able administrator needed to

unify South Vietnam’s competing political and religious

factions. Catholics accused Khanh of discrimination after he

fired several key officials. Buddhists comprised the largest

share of the

non-Catholic population, which

also included

groups such

as the

Hoa Hao

and Cao Dai

religious sects. The Buddhists opposed both Catholic ambitions

and Khanh’s authoritarianism. The stability of the country was

seriously threatened, so Khanh—under pressure from US Ambassador

Maxwell Taylor—began to build a constitutional framework for his

government. He established a High National Council of veteran

statesmen to draft a

constitution and appointed an elderly nationalist, Phan Khac

Suu, his chief of state. The ancient Tran Van Huong

became prime minister. As a result of these institutional

changes, Khanh

could not

act

unilaterally when

the Young

Turks’

demanded

![]()

7

Diem with Chanoff,

In

the Jaws

of History,

p. 121;

Robert S.

McNamara with

Brian VanDeMark,

In Retrospect: The

Tragedy and

Lessons of Vietnam (New York:

Times Books, 1995), 186.

that he fire

Generals Le Van Kim, Tran Van Don, Duong Van “Big” Minh, and

others. Suu needed

to sign

the decree

before it

could become

official, and

the new

chief of

state adamantly refused Khanh’s request.8

Their ambitions

stifled, the Young Turks took matters into their own hands,

demonstrating that Taylor’s lectures to Khanh about creating a

stable civilian government carried

little weight.

On December

20, claiming

they were

responding to rumors

of a

coup against Suu, the Young Turks kidnapped the High

National Councilmen and shipped them to Pleiku.9 Taylor exploded when he found out

what had happened. He told the Young Turks that Washington was

“tired of coups,” and warned them that the White House could not

support Saigon if the generals continued to act rashly. The

ambassador then announced that because Khanh had become too much

of a problem for Washington, it might not be possible for the

United States to maintain its support for him.10

Khanh sensed an opportunity to earn some goodwill among the

Vietnamese, and rose to the Young Turks’ defense. Much to

Taylor’s chagrin, Khanh suggested that Washington should recall

its ambassador to Vietnam.11

Khanh’s

ploy failed,

and he

did not

remain in

power much

longer. On

14 February

1965, he dissolved the current government and asked Dr. Phan Huy

Quat to build a new administration. While civilians technically

led this new government, Khanh retained control over the Army of

the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), and through it controlled

![]()

8 Diem with

Chanoff,

In the Jaws

of History,

119-121; Ky

with Wolf,

Buddha’s Child, 109; Fitzgerald,

Fire in the Lake,

248-256.

9

Diem with Chanoff,

In the

Jaws of History,

122; Ky with

Wolf, Buddha’s

Child, 110.

10

Gardner,

Pay

any Price,

159-160.

11

Diem with Chanoff,

In the

Jaws of

History, 122.

much of South

Vietnamese policymaking. Unfortunately for Khanh, Colonel Pham

Ngoc Thao and General Lam Van tried to usurp power, proving that

South Vietnamese

stability remained fragile. Khanh sought out Ky for protection,

but the attempted coup marked the end

of Khanh’s

reign. Thao

and Van

agreed to

cease their

efforts in

exchange for

Khanh’s resignation and exile. With the junta leader

gone, the Young Turks were now the dominant military faction in

South Vietnam.12

Prime Minister

Quat survived only long enough to oversee Lyndon Johnson’s

introduction of combat troops into Vietnam. As a northerner,

Quat’s leadership in Saigon frustrated many southerners, so he

was never able to rally all of the rival military and civilian

factions in South Vietnam. While Quat successfully secured an

agreement to dissolve the Armed Forces Council, the body through

which the military had influenced government policy since the

Khanh era, civilian control of the Republic of Vietnam was

tenuous. Ky had already made it clear that the military would

seize power if the civilians did anything that he considered

treasonous. The dissolution of the Armed Forces Council did not

change the balance of power in Saigon. Lacking a strong popular

base or military support,

Quat stood on

a precipice.

He finally

fell from

power after

he tried

to replace

two of his Cabinet ministers. When southern politicians

successfully discouraged Suu from signing the termination

orders, government operations ground to a halt.13

![]()

The Young Turks stepped in to resolve the impasse and, after a

three-hour meeting on 12 June

1965, Ky

dispatched an aide

to announce

that Quat

was resigning

in favor of

military rule.

Ky accepted

the mantle

of prime

minister and

appointed Thieu

his

12 Ibid,

122-123.

13

Diem with Chanoff,

In the

Jaws of History,

124-147; Gardner,

Pay any

Price, 175-176.

chief of state.

Ky stood in the spotlight, and Thieu’s status as chief of state

was largely ceremonial. Thieu also chaired a committee of

officers called the Directorate, however, which served as the

real authority in South Vietnam.

Through the Directorate, Thieu exercised considerable influence

over government policies. The White House was not

particularly fond

of Quat,

so few US officials

protested this coup.

Taylor simply

shrugged off the coup under the rationalization that the

military would always rule the Republic of Vietnam.14

Undersecretary of State George Ball was an exception; he argued

that the latest coup demonstrated that South Vietnam was too

weak to remain stable, even with American aid. “These people are

clowns,” he lamented.15

The Johnson

administration became divided over the quality of the new Ky

regime. Deputy Ambassador Alex Johnson described Ky as an

“unguided missile,” and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara

condemned the South Vietnamese prime minister, who “drank,

gambled, and womanized heavily.” Ky unnerved US officials

because of his flashy dress (he wore a “zippered black flying

suit belted with twin pearl- handled

revolvers”) and

his tendency

to make outrageous statements.16

He told

London’s Sunday Mirror, for example, that he admired Hitler, who “pulled his

country together when it was in a terrible state.” To stave off

the communist threat, Ky proclaimed, “We

![]()

14 Diem with Chanoff,

In the Jaws of History, 146-147, 158; Gardner,

Pay any Price, 224-225;

Lien-Hang T. Nguyen,

Hanoi’s

War: An

International History of

the War

for Peace in Vietnam

(Chapel Hill: University

of North

Carolina Press,

2012), 138;

Kahin,

Intervention, 344-345.

15

Gardner,

Pay

any Price,

224-225.

16

McNamara with

VanDeMark,

In

Retrospect, 186.

need four or

five Hitlers in Vietnam.”17 Despite such hyperbole,

President Johnson appreciated Ky and Thieu’s capacity to

maintain stability after an extended period of chaos. Johnson

was also heartened by Ky’s promise to defeat the enemy, rebuild

the countryside, stabilize the economy, and improve South

Vietnamese democracy.18 Ky appealed

to Johnson’s

highest

priorities for

Vietnam:

stability and

Americanized nation building.

Perhaps because

LBJ held

such high

hopes for

what could

be accomplished

in South Vietnam, he was particularly disenchanted when

Ky failed to deliver.

Most US

officials grew anxious about the South Vietnamese leaders who

succeeded Diem.

Alex Johnson

regarded the

Young Turks

as xenophobic

nationalists who had grown weary of democracy. The deputy ambassador reported

that the new government underestimated the complexity of the

policy challenges it faced, and overestimated the capacity of

its bureaucracy to implement Saigon’s orders. Maxwell Taylor

appeared grateful that Ky seemed genuinely intent on mobilizing

his country for war, but he considered the young airman too

immature and inexperienced for the prime minister’s office.19

![]()

17 Quoted in

Congressional

Record

[Hereafter,

CR],

89th Cong., 1st

sess., 1965.

Vol. 111, pt.

12, S: 17146-17154.

18

Lyndon B.

Johnson,

The

Vantage Point:

Perspectives

of the

Presidency, 1963-1969

(New York:

Holt, Rinehart

and Winston,

1971),

242.

19

Telegram from the Embassy in Vietnam to the Department of State,

13 June 1965, Foreign

Relations of

the United

States

[Hereafter,

FRUS],

June-December 1965, Vol.

III: Document 2; Telegram

from the

Embassy in

Vietnam to

the Department of State,

17 June 1965,

FRUS, June-December

1965, Vol. III: Document 5. Documents from FRUS that are

available in print or PDF format will include page numbers

before the document number. All documents that do not include

page numbers are available online as HTML

files.

Ky and Thieu

had to face all of the old tensions that had destroyed the

previous regimes that emerged after 1963. The military remained

fractious. The new Cabinet seemed competent, but there were many

competing political factions. Catholics were wary of Ky, a

Buddhist, and Buddhists disliked Thieu, a Catholic. Taylor

regarded the new

regime as

unwieldy. He

noted that

the

government’s decisions were

divided among

numerous committees, and doubted that Ky would prove capable of

managing all of them. Taylor resigned himself to supporting Ky,

however, in the belief that this regime was probably the best

Washington could achieve for the moment.20

Taylor’s

assessments of Ky were partially colored by his distaste for the

South Vietnamese. In a long letter to Ky, he described the

military and economic problems he wanted corrected. He concluded

by raising an issue that he had addressed on many occasions

with Ky.

Taylor

lamented the