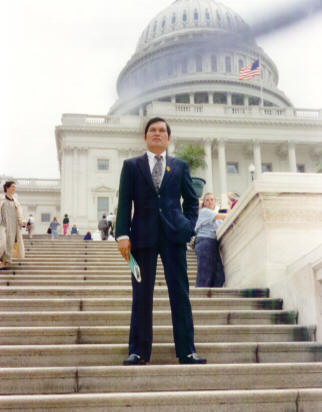

at Capitol. June 19.1996

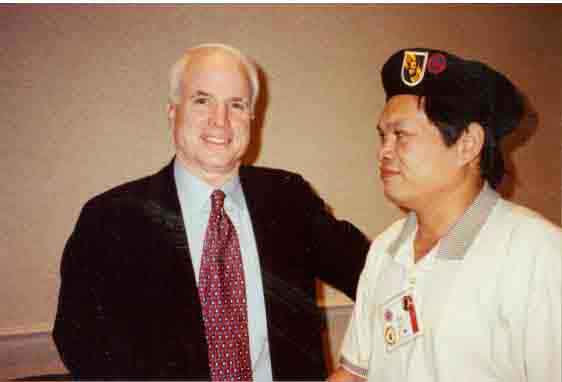

with Sen. JohnMc Cain

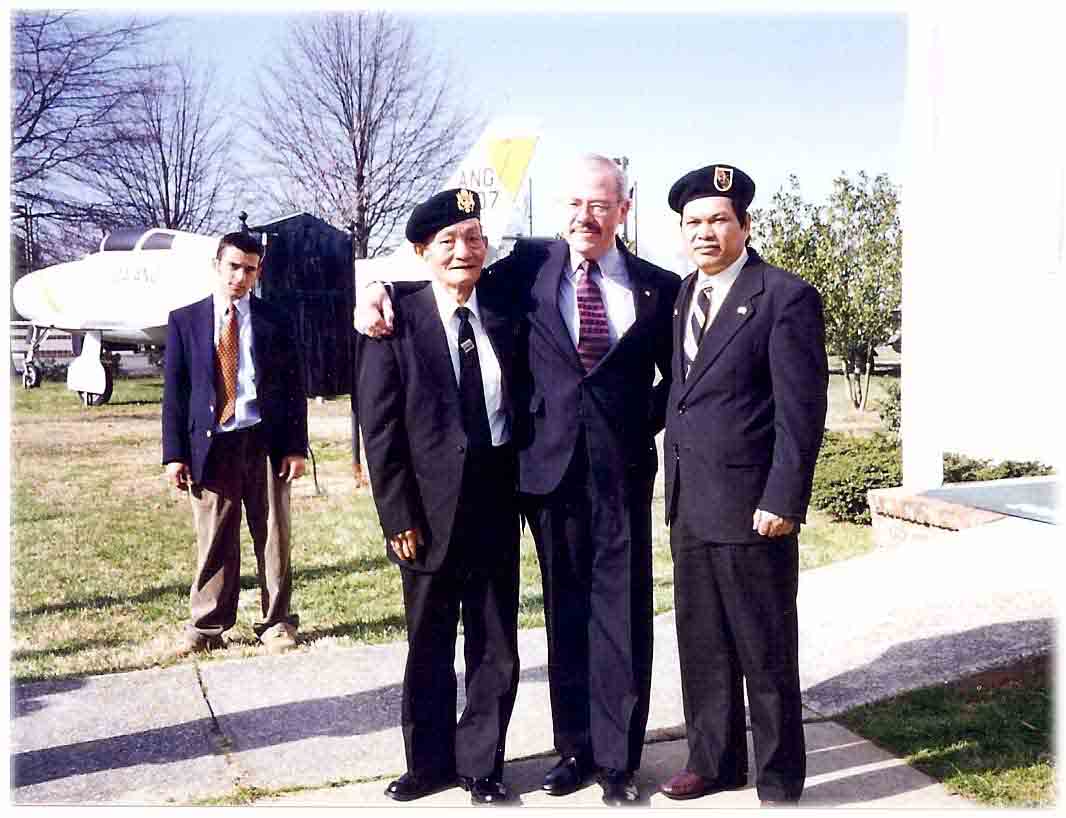

with Congressman Bob Barr

with General John K Singlaub

CNBC .Fox .FoxAtl .. CFR. CBS .CNN .VTV.

.WhiteHouse .NationalArchives .FedReBank

.Fed Register .Congr Record .History .CBO

.US Gov .CongRecord .C-SPAN .CFR .RedState

.VideosLibrary .NationalPriProject .Verge .Fee

.JudicialWatch .FRUS .WorldTribune .Slate

.Conspiracy .GloPolicy .Energy .CDP .Archive

.AkdartvInvestors .DeepState .ScieceDirect

.NatReview .Hill .Dailly .StateNation .WND

-RealClearPolitics .Zegnet .LawNews .NYPost

.SourceIntel .Intelnews .QZ .NewAme

.GloSec .GloIntel .GloResearch .GloPolitics

.Infowar .TownHall .Commieblaster .EXAMINER

.MediaBFCheck .FactReport .PolitiFact .IDEAL

.MediaCheck .Fact .Snopes .MediaMatters

.Diplomat .NEWSLINK .Newsweek .Salon

.OpenSecret .Sunlight .Pol Critique .

.N.W.Order .Illuminatti News.GlobalElite

.NewMax .CNS .DailyStorm .F.Policy .Whale

.Observe .Ame Progress .Fai .City .BusInsider

.Guardian .Political Insider .Law .Media .Above

.SourWatch .Wikileaks .Federalist .Ramussen

.Online Books .BREIBART.INTERCEIPT.PRWatch

.AmFreePress .Politico .Atlantic .PBS .WSWS

.NPRadio .ForeignTrade .Brookings .WTimes

.FAS .Millenium .Investors .ZeroHedge .DailySign

.Propublica .Inter Investigate .Intelligent Media

.Russia News .Tass Defense .Russia Militaty

.Scien&Tech .ACLU .Veteran .Gateway. DeepState

.Open Culture .Syndicate .Capital .Commodity

.DeepStateJournal .Create .Research .XinHua

.Nghiên Cứu QT .NCBiển Đông .Triết Chính Trị

.TVQG1 .TVQG .TVPG .BKVN .TVHoa Sen

.Ca Dao .HVCông Dân .HVNG .DấuHiệuThờiĐại

.BảoTàngLS.NghiênCứuLS .Nhân Quyền.Sài Gòn Báo

.Thời Đại.Văn Hiến .Sách Hiếm.Hợp Lưu

.Sức Khỏe .Vatican .Catholic .TS KhoaHọc

.KH.TV .Đại Kỷ Nguyên .Tinh Hoa .Danh Ngôn

.Viễn Đông .Người Việt.Việt Báo.Quán Văn

.TCCS .Việt Thức .Việt List .Việt Mỹ .Xây Dựng

.Phi Dũng .Hoa Vô Ưu.ChúngTa .Eurasia.

CaliToday .NVR .Phê Bình . TriThucVN

.Việt Luận .Nam Úc .Người Dân .Buddhism

.Tiền Phong .Xã Luận .VTV .HTV .Trí Thức

.Dân Trí .Tuổi Trẻ .Express .Tấm Gương

.Lao Động .Thanh Niên .Tiền Phong .MTG

.Echo .Sài Gòn .Luật Khoa .Văn Nghệ .SOTT

.ĐCS .Bắc Bộ Phủ .Ng.TDũng .Ba Sàm .CafeVN

.Văn Học .Điện Ảnh .VTC .Cục Lưu Trữ .SoHa

.ST/HTV .Thống Kê .Điều Ngự .VNM .Bình Dân

.Đà Lạt * Vấn Đề * Kẻ Sĩ * Lịch Sử *.Trái Chiều

.Tác Phẩm * Khào Cứu * Dịch Thuật * Tự Điển *

KIM ÂU -CHÍNHNGHĨA -TINH HOA - STKIM ÂU

CHÍNHNGHĨA MEDIA-VIETNAMESE COMMANDOS

BIÊTKÍCH -STATENATION - LƯUTRỮ -VIDEO/TV

DICTIONAIRIES -TÁCGỈA-TÁCPHẨM - BÁOCHÍ . WORLD - KHẢOCỨU - DỊCHTHUẬT -TỰĐIỂN -THAM KHẢO - VĂNHỌC - MỤCLỤC-POPULATION - WBANK - BNG ARCHIVES - POPMEC- POPSCIENCE - CONSTITUTION

VẤN ĐỀ - LÀMSAO - USFACT- POP - FDA EXPRESS. LAWFARE .WATCHDOG- THỜI THẾ - EIR.

ĐẶC BIỆT

-

The Invisible Government Dan Moot

-

The Invisible Government David Wise

ADVERTISEMENT

Le Monde -France24. Liberation- Center for Strategic

https://www.intelligencesquaredus.org/

Space - NASA - Space News - Nasa Flight - Children Defense

Pokemon.Game Info. Bách Việt Lĩnh Nam.US History

with Ross Perot, Billionaire

with General Micheal Ryan

US DEBT CLOCK .WORLDOMETERS .TRÍ TUỆ MỸ . SCHOLARSCIRCLE. CENSUS - SCIENTIFIC-COVERTACTION. EPOCH ĐKN - REALVOICE - JUSTNEWS - NEWSMAX - BREIBART - WARROOM - REDSTATE - PJMEDIA - EPV - REUTERS - AP - NTD REPUBLIC - VIỆT NAM - BBC - VOA - RFI - RFA - HOUSE - TỬ VI - VTV - HTV - PLUTO - BLAZE - INTERNET - SONY - CHINA SINHUA - FOXNATION - FOXNEWS - NBC - ESPN - SPORT - ABC- LEARNING - IMEDIA - NEWSLINK - WHITEHOUSE CONGRESS - FED REGISTER - OAN - DIỄN ĐÀN - UPI - IRAN - DUTCH - FRANCE 24 - MOSCOW - INDIA - NEWSNOW NEEDTOKNOW - REDVOICE - NEWSPUNCH - CDC - WHO - BLOOMBERG - WORLDTRIBUNE - WND - MSNBC- REALCLEAR

POPULIST PRESS - PBS - SCIENCE - HUMAN EVENT - REPUBLIC BRIEF - AWAKENER - TABLET - AMAC - LAW - WSWS PROPUBICA -INVESTOPI-CONVERSATION - BALANCE - QUORA - FIREPOWER - GLOBAL- NDTV- ALJAZEER- TASS- DAWN

NHẬN ĐỊNH - QUAN ĐIỂM

"No book to date conveys the hideousness of the

Vietnam War as thoroughly as this one."

-Publishers Weekly

THE PHOENIX PROGRAM

INTRODUCTION

It was well after midnight. Elton Manzione, his

wife, Lynn, and I sat at their kitchen table, drinking steaming cups

of coffee. Rock 'n' roll music throbbed from the living room. A

lean, dark man with large Mediterranean features, Elton was

chain-smoking Pall Malls and telling me about his experiences as a

twenty-year-old U.S. Navy SEAL in Vietnam in 1964. It was hot and

humid that sultry Georgia night, and we were exhausted; but I

pressed him for more specific information. "What was your most

memorable experience?" I asked.

Elton looked down and with considerable effort,

said quietly, "There's one experience I remember very well. It was

my last assignment. I remember my last assignment very well.

"They," Elton began, referring to the Navy

commander and Special Forces colonel who issued orders to the SEAL

team, "called the three of us [Elton, Eddie Swetz, and John Laboon]

into the briefing room and sat us down. They said they were having a

problem at a tiny village about a quarter of a mile from North

Vietnam in the DMZ. They said some choppers and recon planes were

taking fire from there. They never really explained why, for

example, they just didn't bomb it, which was their usual response,

but I got the idea that the village chief was politically connected

and that the thing had to be done quietly.

"We worked in what were called hunter-killer

teams," Elton explained. "The hunter team was a four-man unit,

usually all Americans, sometimes one or two Vietnamese or Chinese

mercenaries called counterterrorists -- CTs for short. Most CTs were

enemy soldiers who had deserted or South Vietnamese criminals. Our

job was to find the enemy and nail him in place -- spot his

position, then go back to a prearranged place and call in the killer

team. The

killer team was usually twelve to twenty-five

South

Vietnamese Special Forces led by Green Berets.

Then we'd join up with the killer team and take out the enemy."

But on this particular mission, Elton explained,

the SEALs went in alone. "They said there was this fifty-one-caliber

antiaircraft gun somewhere near the village that was taking potshots

at us and that there was a specific person in the village operating

the gun. They give us a picture of the guy and a map of the village.

It's a small village, maybe twelve or fifteen hooches. 'This is the

hooch,' they say. 'The guy sleeps on the mat on the left side. He

has two daughters.' They don't know if he has a mama-san or where

she is, but they say, 'You guys are going to go in and get this guy.

You [meaning me] are going to snuff him.' Swetz

is gonna find out where the gun is and blow it. Laboon is gonna hang

back at the village gate covering us. He's the stoner; he's got the

machine gun. And I'm gonna go into the hooch and snuff this guy.

"'What you need to do first,' they say, 'is sit

alongside the trail [leading from the village to the gun] for a day

or two and watch where this guy goes. And that will help us uncover

the gun.' Which it did. We watched him go right to where the gun

was. We were thirty yards away, and we watched for a while. When we

weren't watching, we'd take a break and go another six hundred yards

down the trail to relax. And we did that for maybe two days --

watched him coming and going -- and got an idea of his routine: when

he went to bed; when he got up; where he went. Did he go behind the

hooch to piss? Did he go into the jungle? That sort of thing.

"They told us, 'Do that. Then come back and tell

us what you found out.' So we went back and said, 'We know where the

gun is,' and we showed them where it was on the map. We were back in

camp for about six hours, and they said, 'Okay, you're going out at

o-four-hundred tomorrow. And it's like we say, you [meaning me] are

going to snuff the guy, Swetz is going to take out the gun, and

Laboon's going to cover the gate.'"

Elton explained that on special missions like

this the usual procedure was to "snatch" the targeted VC cadre and

bring him back to Dong Ha for interrogation. In that case Elton

would have slipped into the hooch and rendered the cadre

unconscious, while Swetz demolished the antiaircraft gun and Laboon

signaled the killer team to descend upon the village in its black

CIA-supplied helicopters. The SEALs and their prisoner would then

climb on board and be extracted.

In this case, however, the cadre was targeted for

assassination.

"We left out of Cam Lo," Elton continued. "We

were taken by boat partway up the river and walked in by foot --

maybe two and a half, three miles. At four in the morning we start

moving across an area that was maybe a hundred yards wide; it's a

clearing running up to the village. We're wearing black pajamas, and

we've got black paint on our faces. We're doing this very carefully,

moving on the ground a quarter of an inch at a time -- move, stop,

listen; move, stop, listen. To check for trip wires, you take a

blade of grass and put it between your teeth, move your head up and

down, from side to side, watching the end of the blade of grass. If

it bends, you know you've hit something, but of course, the grass

never sets off the trip wire, so it's safe.

"It takes us an hour and a half to cross this

relatively short stretch of open grass because we're moving so

slowly. And we're being so quiet we can hardly hear each other, let

alone anybody else hearing us. I mean, I know they're out there --

Laboon's five yards that way, Swetz is five yards to my right -- but

I can't hear them.

"And so we crawl up to the gate. There's no booby

traps. I go in. Swetz has a satchel charge for the fifty-one-caliber

gun and has split off to where it is, maybe sixty yards away. Laboon

is sitting at the gate. The village is very quiet. There are some

dogs. They're sleeping. They stir, but they don't even growl. I go

into the hooch, and I spot my person. Well, somebody stirs in the

next bed. I'm carrying

my commando knife, and one of the things we

learned is how to kill somebody instantly with it. So I put my hand

over her mouth and come up under the second rib, go through the

heart, give it a flick; it snaps the spinal cord. Not thinking!

Because I think 'Hey!' Then I hear the explosion go off and I know

the gun is out. Somebody else in the corner starts to stir, so I

pull out the sidearm and put it against her head and shoot her.

She's dead. Of course, by this time the whole village is awake. I go

out, waiting for Swetz to come, because the gun's been blown. People

are kind of wandering around, and I'm pretty dazed. And I look back

into the hooch, and there were two young girls. I'd killed the wrong

people."

Elton Manzione and his comrades returned to their

base at Cam Lo. Strung out from Dexedrine and remorse, Elton went

into the ammo dump and sat on top of a stack of ammunition crates

with a grenade, its pin pulled, between his legs and an M-16 cradled

in his arms. He sat there refusing to budge until he was given a

ticket home.

***

In early 1984 Elton Manzione was the first person

to answer a query I had placed in a Vietnam veterans' newsletter

asking for interviews with people who had served in the Phoenix

program. Elton wrote to me, saying, "While I was not a participant

in Phoenix, I was closely involved in what I think was the

forerunner. It was part of what was known as OPLAN 34. This was the

old Leaping Lena infiltration program for LRRP [long-range

reconnaissance patrol] operations into Laos. During the time I was

involved it became the well-known Delta program. While all this

happened before Phoenix, the operations were essentially the same.

Our primary function was intelligence gathering, but we also carried

out the 'undermining of the infrastructure' types of things such as

kidnapping, assassination, sabotage, etc.

"The story needs to be told," Elton said,

"because the whole aura of the Vietnam War was influenced by what

went on in the 'hunter-killer' teams of Phoenix, Delta, etc. That

was the point at which many of us realized we were no longer the

good guys in the white hats defending freedom -- that we were

assassins, pure and simple. That disillusionment carried over to all

other aspects of the war and was eventually responsible for it

becoming America's most unpopular war."

***

The story of Phoenix is not easily told. Many of

the participants, having signed nondisclosure statements, are

legally prohibited from telling what they know. Others are silenced

by their own consciences. Still others are professional soldiers

whose careers would suffer if they were to reveal the secrets of

their employers. Falsification of records makes the story even

harder to prove. For example, there is no record of Elton Manzione's

ever having been in Vietnam. Yet, for reasons which are explained in

my first book, The Hotel Tacloban, I was predisposed to believe

Manzione. I had confirmed that my father's military records were

deliberately altered to show that he had not been imprisoned for two

years in a Japanese prisoner of war camp in World War II. The

effects of the cover-up were devastating and ultimately caused my

father to have a heart attack at the age of forty-five. Thus, long

before I met Elton Manzione, I knew the government was capable of

concealing its misdeeds under a cloak of secrecy, threats, and

fraud. And I knew how terrible the consequences could be.

Then I began to wonder if cover-ups like the one

concerning my father had also occurred in the Vietnam War, and that

led me in the fall of 1983 to visit David Houle, director of veteran

services in New Hampshire. I asked Dave Houle if there was a part of

the Vietnam War that had been concealed, and without hesitation he

replied, "Phoenix." After explaining a little about it, he mentioned

that one of his clients had been in the program, then added that his

client's service records -- like those of Elton

Manzione's and my father's -- had been altered.

They showed that he had been a cook in Vietnam.

I asked to meet Houle's client, but the fellow

refused. Formerly with Special Forces in Vietnam, he was disabled

and afraid the Veterans Administration would cut off his benefits if

he talked to me.

That fear of the government, so incongruous on

the part of a war veteran, made me more determined than ever to

uncover the truth about Phoenix, a goal which has taken four years

to accomplish. That's a long time to spend researching and writing a

book. But I believe it was worthwhile, for Phoenix symbolizes an

aspect of the Vietnam War that changed forever the way Americans

think about themselves and their government.

Developed in 1967 by the Central Intelligence

Agency (CIA), Phoenix combined existing counterinsurgency programs

in a concerted effort to "neutralize" the Vietcong infrastructure

(VCI). The euphemism "neutralize" means to kill, capture, or make to

defect. The word "infrastructure" refers to those civilians

suspected of supporting North Vietnamese and Vietcong soldiers like

the one targeted in Elton Manzione's final operation.

Central to Phoenix is the fact that it targeted

civilians, not soldiers. As a result, its detractors charge that

Phoenix violated that part of the Geneva Conventions guaranteeing

protection to civilians in time of war. "By analogy," said Ogden

Reid, a member of a congressional committee investigating Phoenix in

1971, "if the Union had had a Phoenix program during the Civil War,

its targets would have been civilians like Jefferson Davis or the

mayor of Macon, Georgia."

Under Phoenix, or Phung Hoang, as it was called

by the Vietnamese, due process was totally nonexistent. South

Vietnamese civilians whose names appeared on blacklists could be

kidnapped, tortured, detained for two years without trial, or even

murdered, simply on the word of an anonymous informer. At its height

Phoenix managers imposed quotas of eighteen hundred neutralizations

per month on the people running the program in the field, opening up

the program to abuses by corrupt security officers, policemen,

politicians, and racketeers, all of whom extorted innocent civilians

as well as VCI. Legendary CIA officer Lucien Conein described

Phoenix as "A very good blackmail scheme for the central government.

'If you don't do what I want, you're VC."'

Because Phoenix "neutralizations" were often

conducted at midnight while its victims were home, sleeping in bed,

Phoenix proponents describe the program as a "scalpel" designed to

replace the "bludgeon" of search and destroy operations, air

strikes, and artillery barrages that indiscriminately wiped out

entire villages and did little to "win the hearts and minds" of the

Vietnamese population. Yet, as Elton Manzione's story illustrates,

the scalpel cut deeper than the U.S. government admits. Indeed,

Phoenix was, among other things, an instrument of counterterror --

the psychological warfare tactic in which VCI members were brutally

murdered along with their families or neighbors as a means of

terrorizing the neighboring population into a state of submission.

Such horrendous acts were, for propaganda purposes, often made to

look as if they had been committed by the enemy.

This book questions how Americans, who consider

themselves a nation ruled by laws and an ethic of fair play, could

create a program like Phoenix. By scrutinizing the program and the

people who participated in it and by employing the program as a

symbol of the dark side of the human psyche, the author hopes to

articulate the subtle ways in which the Vietnam War changed how

Americans think about themselves. This book is about terror and its

role in political warfare. It will show how, as successive American

governments sink deeper and deeper into the vortex of covert

operations -- ostensibly to combat terrorism and Communist

insurgencies -- the American people gradually lose touch with the

democratic ideals that

once defined their national self-concept. This

book asks what happens when Phoenix comes home to roost.

SOUTHEAST ASIA

CORPS AND PROVINCES OF SOUTH VIETNAM

CIA officer Ralph Johnson, in safari jacket and

baseball cap, standing beside his donkey in Muong Sai, Laos, circa

1959 (Johnson family collection)

Phoenix officials, spring 1969; left to right:

National Police officer Duong Tan Huu; Lt. Col. Loi Nguyen Tan;

Phoenix Director Evan J. Parker, Jr.; Parker's replacement, John H.

Mason; Lt. Col. Robert Inman; two unidentified Vietnamese (Parker

family collection)

American pacification officials in Binh Dinh

Province, circa 1963; left to right: Major Harry "Buzz" Johnson;

State Department officer Val Vahovich; USIS officer Frank

W. Scotton; Special Forces Sergeant Joe Vaccaro

(Johnson family collection)

Nelson H. Brickham, Jr., in Dalat, circa 1966

(Brickham family collection)

William Colby, circa 1969 (Colby family

collection)

Tulius Acampora with General Nguyen Ngoc Loan,

circa 1966 (Acampora family collection)

Acampora with Major Nguyen Mau (Acampora family

collection)

GALLERY

Colonel William "Pappy" Grieves walking behind

National Police Field Forces chief Colonel Nguyen Van Dai, February

1970 (Grieves family collection)

Khanh Hoa Province Interrogation Center, Nha

Trang, circa 1966 (Brickham family collection)

Province Interrogation Center, unidentified

province, circa 1966 (Brickham family collection)

Colonel Douglas Dillard with the director of the

Military Security Service, General Vu Duc Nhuan, circa 1969 (Dillard

family collection)

Province Interrogation Center program director

Robert Slater

in Dalat, December 1968, holding Bridget Bardot

Rose, with Vietnamese Special Branch officers in background (Slater

family collection)

Slater flanked by PIC program advisers Frank

Cerrincione, left, and Orrin DeForest in Bao Loc, Lam Dong Province,

December 1968 (Slater family collection)

Phoenix officer Warren Milberg standing beside I

Corps National Police Chief Vu Luong, in Danang, spring 1968

(Milberg family collection)

THE PHOENIX PROGRAM -- PICTURE GALLERY

Quang Tri Province Provincial Reconnaissance Unit

(PRU), circa 1967 (Milberg family collection)

Delta PRU adviser John Wilbur with the Kien Hoa

Province PRU team, circa 1967 (Wilbur family collection)

PRU cadre, Vung Tau training center, circa 1967

(Wilbur family collection)

II Corps PRU advisers, circa 1969; left to right:

Aussie Ostera; Blue Carter; Captain John McGeehan; Sergeant John

Fanning; Major Paul Ogg; Captain Charles Aycock; Captain John

Vaughn; Sergeant Buzz Brewer; Sergeant Al Young; Sergeant Larry

Jones (Ogg family collection)

II Corps PRU adviser Paul Ogg with Colonel Ruel

P. Scoggins, circa 1970 (Ogg family collection)

Phoenix training officer Lt. Col. Walter V.

Kolon, right, with John E. MacDonald, senior State Department

representative to the Phoenix staff, circa 1969 (Kolon family

collection)

From left: Phoenix Director John H. Mason,

Phoenix Operations Chief Lt. Col. Thomas P. McGrevey, and Deputy

Phoenix Director Colonel James W. Newman, circa 1970 (Newman family

collection)

GALLERY

From left: Phung Hoang chief Colonel Ty Trong

Song, John Mason, James Newman, and senior Phung Hoang

officer Lt. Col. Pham Van Cao, circa 1970 (Newman

family collection)

Sergeants Ed Murphy, left, and Blane Baisley

outside Dragon Mountain Combined Interrogation Center, 4th Military

Intelligence Detachment, Pleiku Province, circa 1968 (Murphy family

collection)

Public Safety Adviser Douglas McCollum at

National Police Field Force outpost in Darlac Province, circa 1968

(McCollum family collection)

Member of the Bien Hoa special Phoenix team,

displaying Phoenix tattoo

Ancient and Oriental Order of Phoenicians

certificate, provided by Phoenix district adviser Major Claude Alley

Special Police Saigon chief, Major Pham Quant Tan

(Roberts family collection)

Saigon Phoenix Deputy Director Captain Shelby

Roberts, at the beach at Vung Tau, circa 1969 (Roberts family

collection)

GALLERY

Phoenix Directorate staff, circa 1972; left to

right: Operations Chief Lt. Col. George Hudman; Phoenix Director

John S. Tilton; Deputy Director Colonel Herb Allen; Major Carl

Moeller (seated); unidentified secretary; unidentified officer;

unidentified secretary; Major Doug Collins; unidentified secretary;

Sergeant Jim Marcus; unidentified officer, unidentified civilian;

unidentified secretary (Hudman family collection)

Phoenix Directorate function, circa 1971; left to

right: Deputy Director Colonel Chester B. McCoid; Director John S.

Tilton; Lt. Col. Russ Cooley; unidentified Public Safety officer;

Colonel Ly Trong Song; National Police adviser Frank Walton; Captain

Albright; Special Branch Deputy Director Dang Van Minh; Lt. Col.

John Ford (McCoid family collection)

Criminal Investigation Division Sergeant William

J. Taylor (Taylor family collection)

CIA officer and senior SOG adviser George French

flanked by Special Operations Group chief Colonel J.F. Sadler, left,

and unidentified SOG officer, circa 1971 (French family collection)

Lt. Col. Walter Kolon and Lt. Col. Al Weidhas at

a Tai Kwon Do exhibition in Saigon in 1969, sponsored by the

Vietnamese American Association (Baillargeon family collection)

Phoenix officers at a farewell ceremony for State

Department officer Seton Shanley; left to right: Captain Paul

Baillargeon; National Police Chief Colonel Tran Van Hai; John Mason;

Colonel Robert E. Jones; Captain Richard Bradish; Seton Shanley;

Charles Phillips; unidentified Vietnamese officer (Baillargeon

family collection)

CIA officers Bruce Lawlor and Patry Loomis in

Quang Nam Province, circa 1972 (Lawlor family collection)

THE PHOENIX PROGRAM

CHAPTER 1: Infrastructure

What is the VCI? Is it a farmer in a field with a

hoe in his hand and a grenade in his pocket, a deranged subversive

using women and children as a shield? Or is it a self- respecting

patriot, a freedom fighter who was driven underground by corrupt

collaborators and an oppressive foreign occupation army?

In his testimony regarding Phoenix before the

Senate Foreign Relations Committee in February 1970, former Director

of Central Intelligence William Colby defined the VCI as "about

75,000 native Southerners" whom in 1954 "the Communists took north

for training in organizing, propaganda and subversion." According to

Colby, these cadres returned to the South, "revived the networks

they had left in 1954," and over several years formed the National

Liberation Front (NLF), the People's

Revolutionary party, liberation committees, which

were

"pretended local governments rather than simply

political bodies," and the "pretended Provisional Revolutionary

Government of South Vietnam.

Together," testified Colby, "all of these

organizations and their local manifestations make up the VC

Infrastructure." [1]

A political warfare expert par excellence, Colby,

of course, had no intentions of portraying the VCI in sympathetic

terms. His abbreviated history of the VCI, with its frequent use of

the word "pretended," deliberately oversimplifies and distorts the

nature and origin of the revolutionary forces lumped under the

generic term "VCI." To understand properly Phoenix and its prey, a

more detailed and objective account is required. Such an account

cannot begin in 1954 -- when the Soviet Union, China, and the United

States split Vietnam along the sixteenth parallel, and the United

States first intervened in Vietnamese affairs -- but must

acknowledge one hundred years of French colonial oppression. For it

was colonialism which begat the VCI, its strategy of protracted

political warfare, and its guerrilla and terror tactics.

The French conquest of Vietnam began in the

seventeenth century with the arrival of Jesuit priests bent on

saving pagan souls. As Vietnam historian Stanley Karnow notes in his

book Vietnam: A History, "In 1664 ... French religious leaders and

their business backers formed the Society of French Missionaries to

advance Christianity in Asia. In the same year, by no coincidence,

French business leaders and their religious backers created the East

India Company to increase trade ....

Observing this cozy relationship in Vietnam, an

English competitor reported home that the French had arrived, 'but

we cannot make out whether they are here to seek trade or to conduct

religious propaganda.'"

"Their objective, of course," Karnow quips, "was

to do both." [2]

For the next two centuries French priests

embroiled

themselves in Vietnamese politics, eventually

providing a pretext for military intervention. Specifically, when a

French priest was arrested for plotting against the emperor of

Vietnam in 1845, the French Navy shelled Da Nang City, killing

hundreds of people, even though the priest had escaped unharmed to

Singapore. The Vietnamese responded by confiscating the property of

French Catholics, drowning a few Jesuits, and cutting in half,

lengthwise, a number of Vietnamese priests.

Soon the status quo was one of open warfare. By

1859 French Foreign Legionnaires had arrived en masse and had

established fortified positions near major cities, which they

defended against poorly armed nationalists staging hit-and- run

attacks from bases in rural areas. Firepower prevailed, and in 1861

a French admiral claimed Saigon for France, "inflicting heavy

casualties on the Vietnamese who resisted." [3] Fearing that the

rampaging French might massacre the entire city, the emperor

abdicated ownership of three provinces adjacent to Saigon, along

with Con Son Island, where the French immediately built a prison for

rebels. Soon thereafter Vietnamese ports were opened to European

commerce, Catholic priests were permitted to preach wherever

Buddhist or Taoist or Confucian souls were lurking in the darkness,

and France was guaranteed "unconditional control over all of

Cochinchina." [4]

By 1862 French colonialists were reaping

sufficient economic benefits to hire Filipino and Chinese mercenary

armies to help suppress the burgeoning insurgency.

Resistance to French occupation was strongest in

the north near Hanoi, where nationalists were aligned with anti-

Western Chinese. The rugged mountains of the Central Highlands

formed a natural buffer for the French, who were entrenched in

Cochin China, the southern third of Vietnam centered in Saigon.

The boundary lines having been drawn, the

pacification of Vietnam began in earnest in 1883. The French

strategy was simple and began with a reign of terror: As many

nationalists as could be found were rounded up

and guillotined. Next the imperial city of Hue was plundered in what

Karnow calls "an orgy of killing and looting." [5] The French

disbanded the emperor's Council of Mandarins and replaced it with

French advisers and a bureaucracy staffed by suppletifs --

self-serving Vietnamese, usually Catholics, who collaborated in

exchange for power and position. The suppletif creme de la creme

studied in, and became citizens of, France. The Vietnamese Army was

commanded by French officers, and Vietnamese officers were

suppletifs who had been graduated from the French military academy.

By the twentieth century all of Vietnam's provinces were

administered by suppletifs, and the emperor, too, was a lackey of

the French.

In places where "security" for collaborators was

achieved, Foreign Legionnaires were shifted to the outer perimeter

of the pacified zones and internal security was turned over to

collaborators commanding GAMOs -- group administrative mobile

organizations. The hope was that pacified areas would spread like

oil spots. Suppletifs were also installed in the police and security

forces, where they managed prostitution rings, opium dens, and

gambling casinos on behalf of the French. From the 1880's onward no

legal protections existed for nationalists, for whom a dungeon at

Con Son Prison, torture, and death were the penalties for pride. So,

outgunned and outlawed in their homeland, the nationalists turned to

terrorism -- to the bullet in the belly and the bomb in the cafe.

For while brutal French pacification campaigns prevented the rural

Vietnamese from tending their fields, terrorism did not.

The first nationalists -- the founding fathers of

the VCI -- appeared as early as 1859 in areas like the Ca Mau

Peninsula, the Plain of Reeds, and the Rung Sat -- malaria- infested

swamps which were inaccessible to French forces. Here the

nationalists honed and perfected the guerrilla tactics that became

the trademark of the Vietminh and later the Vietcong. Referred to as

selective terrorism, this meant

the planned assassination of low-ranking

government officials who worked closely with the people; for

example, policemen, mailmen, and teachers. As David Galula explains

in Counter-Insurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice, "Killing

high-ranking counterinsurgency officials serves no purpose since

they are too far removed from the population for their deaths to

serve as examples." [6]

The purpose of selective terror was

psychologically to isolate the French and their suppletifs, while

demonstrating to the rural population the ability of the insurgents

to strike at their oppressors until such time as a general uprising

was thought possible.

In the years following World War I, Vietnamese

nationalists organized in one of three ways: through religious

sects, like the Hoa Hao or Cao Dai, which secretly served as fronts

for anti-French activity; through overt political parties like the

Dai Viets and the Vietnam Quoc Dan Dang (VNQDD); or by becoming

Communists. All formed secret cells in the areas where they

operated, and all worked toward ousting the French.

In return, the French intelligence service, the

Deuxieme Bureau, hired secret agents and informers to identify,

capture, imprison, and murder core members of the underground

resistance.

In instances of open rebellion, stronger steps

were taken. When VNQDD sailors mutinied in 1932 in Yen Bai and

killed their French officers, the French retaliated by bombing

scores of VNQDD villages, killing more than thirty thousand people.

Mass deportations followed, and many VNQDD cadres were driven into

exile. Likewise, when the French caught wind of a general uprising

called for by the Communists, they arrested and imprisoned 90

percent of its leadership. Indeed, the VCI leadership was molded in

Con Son Prison, or Ho Chi Minh University, as it was also known.

There determined nationalists transformed dark dungeons into

classrooms and common criminals into hard-core cadres. With their

lives depending

on their ability to detect spies and agents

provocateurs whom the French had planted in the prisons, these

forefathers of the VCI became masters of espionage and intrigue and

formidable opponents of the dreaded Deuxieme Bureau.

In 1941 the Communist son of a mandarin, Ho Chi

Minh, gathered the various nationalist groups under the banner of

the Vietminh and called for all good revolutionaries "to stand up

and unite with the people, and throw out the Japanese and the

French." [7] Leading the charge were General Vo Nguyen Giap and his

First Armed Propaganda Detachment -- thirty-four lightly armed men

and women who by early 1945 had overrun two French outposts and were

preaching the gospel according to Ho to anyone interested in

independence. By mid-1945 the Vietminh held six provinces near Hanoi

and was working with the forerunner of the CIA, the Office of

Strategic Services (OSS), recovering downed pilots of the U.S.

Fourteenth Air Force. A student of American democracy, Ho declared

Vietnam an independent country in September 1945.

Regrettably, at the same time that OSS officers

were meeting with Ho and exploring the notion of supporting his

revolution, other Americans were backing the French, and when a U.S.

Army officer traded a pouch of opium for Ho's dossier and uncovered

his links to Moscow, all chances of coexistence vanished in a puff

of smoke. The Big Three powers in Potsdam divided Vietnam along the

sixteenth parallel. Chinese forces aligned with General Chiang

Kai-shek and the Kuomintang were given control of the North. In

September 1945 a division of Chinese forces advised by General

Phillip Gallagher arrived in Hanoi, plundered the city, and disarmed

the Japanese. The French returned to Hanoi, drove out the Vietminh,

and displaced Chiang's forces, which obtained Shanghai in exchange.

Meanwhile, Lord Louis Mountbatten (who used the

phoenix as an emblem for his command patch) and the

British were put in charge in the South. Twenty

thousand Gurkhas arrived in Saigon and proceeded to disarm the

Japanese. The British then outlawed Ho's Committee of the South and

arrested its members. In protest the Vietnamese held a general

strike. On September 23 the Brits, buckling under the weight of the

White Man's Burden, released from prison those French Legionnaires

who had collaborated with the Nazis during the occupation and had

administered Vietnam jointly with the Japanese. The Legionnaires

rampaged through Saigon, murdering Vietnamese with impunity while

the British kept stiff upper lips. As soon as they had regained

control of the city, the French reorganized their quislings and

secret police, donned surplus U.S. uniforms, and became the nucleus

of three divisions which had reconquered South Vietnam by the end of

the year. The British exited, and the suppletif Bao Dai was

reinstalled as emperor.

By 1946 the Vietminh were at war with France once

again, and in mid-1946 the French were up to their old tricks --

with a vengeance. They shelled Haiphong, killing six thousand

Vietnamese. Ho slipped underground, and American officials passively

observed while the French conducted "punitive missions ... against

the rebellious Annamese." [8] During the early years of the First

Indochina War, CIA officers served pretty much in that same limited

capacity, urging the French to form counterguerrilla groups to go

after the Vietminh and, when the French ignored them, slipping off

to buy contacts and agents in the military, police, government, and

private sectors.

The outgunned Vietminh, meanwhile, effected their

strategy of protracted warfare. Secret cells were organized, and

guerrilla units were formed to monitor and harass French units,

attack outposts, set booby traps, and organize armed propaganda

teams. Assassination of collaborators was part of their job. Company

and battalion-size units were also formed to engage the French in

main force battles.

By 1948 the French could neither protect their

convoys from ambushes nor locate Vietminh bases. Fearful French

citizens organized private paramilitary self-defense forces and spy

nets, and French officers organized, with CIA advice, commando

battalions (Tien-Doan Kinh Quan) specifically to hunt down Vietminh

propaganda teams and cadres. At the urging of the CIA, the French

also formed composite airborne commando groups, which recruited and

trained Montagnard hill tribes at the coastal resort city of Vung

Tau. Reporting directly to French Central Intelligence in Hanoi and

supplied by night airdrops, French commandos were targeted against

clandestine Vietminh combat and intelligence organizations. The

GCMAs were formed concurrently with the U.S. Army's First Special

Forces at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

By the early 1950s American soldiers were

fighting alongside the French, and the 350-member U.S. Military

Assistance and Advisory Group (MAAG) was in Saigon, dispensing and

accounting for U.S. largess. All in all, from 1950 through 1954, the

United States gave over three billion dollars to the French for

their counterinsurgency in Vietnam, including four million a year as

a retainer for Emperor Bao Dai, who squirreled away the lion's share

in Swiss bank accounts and foreign real estate.

In Apri1 1952, American advisers began training

Vietnamese units. In December 1953, an Army attache unit arrived in

Hanoi, and its officers and enlisted men began interrogating

Vietminh prisoners. While MAAG postured to take over the Vietnamese

Army from the French, the Special Technical and Economic Mission

provided CIA officers, under station chief Emmett McCarthy, with the

cover they needed to mount political operations and negotiate

contracts with the government of Vietnam (GVN).

Finally, in July 1954, after the Vietminh had

defeated the French at Dien Bien Phu, a truce was declared at

the Geneva Conference. Vietnam was divided along

the seventeenth parallel, pending a nationwide election to be held

in 1956, with the Vietminh in control in the North and Bao Dai in

control in the South. The French were to withdraw from the North and

the Vietminh from the South, where the United States was set to

displace the French and install its own candidate, Ngo Dinh Diem, a

Catholic mandarin from Hue. The CIA did this by organizing a cross

section of Vietnamese labor leaders and intellectuals into the Can

Lao Nham Vi (Personalist Labor party). Diem and his brothers, Nhu,

Can, and Thuc (the archbishop of Hue), thereafter controlled tens of

thousands of Can Lao followers through an interlocking maze of

clandestine cells present in the military, the police and security

services, the government, and private enterprise.

In Vietnamese History from 1939-1975, law

professor Nguyen Ngoc Huy, a Dai Viet politician who was exiled by

Diem in 1954, says about the Diem regime: "They persecuted those who

did not accept their orders without discussion, and tolerated or

even encouraged their followers to take bribes, because a corrupt

servant must be loyal to them out of fear of punishment

To obtain an

interesting position, one had to fulfill the

three D conditions: Dang [the Can Lao party]; Dao [the Catholic

religion]; and Dia phuong [the region -- Central Vietnam]. Those who

met these conditions and moreover had served Diem before his victory

over his enemies in 1955 enjoyed unbelievable promotions." [9]

Only through a personality cult like the Can Lao

could the CIA work its will in Vietnam, for Diem did not issue from

or have the support of the Buddhist majority. He was, however, a

nationalist whose anti- French reputation enabled the Americans to

sell themselves to the world as advisers to a sovereign government,

not as colonialists like the French. In exchange, Diem arranged for

Can Lao businessmen and their American associates to obtain

lucrative government contracts and commercial interests once owned

exclusively

by the French, with a percentage of every

transaction going to the Can Lao. Opposed to Diem were the French

and their suppletifs in the Surete and the Vietnamese Mafia, the

Binh Xuyen. Together with the Hoa Hao and Cao Dai religious sects,

these groups formed the United Sect Front and conspired against the

United States and its candidate, Diem.

Into this web of intrigue, in January 1954,

stepped U.S. Air Force Colonel Edward Lansdale. A confidential agent

of Director of Central Intelligence Allen Dulles and his brother,

Secretary of State John Dulles, Lansdale defeated the United Sect

Front by either killing or buying off its leaders. He then hurriedly

began to build, from the top down, a Vietnam infused with American

values and dollars, while the Vietcong -- as Lansdale christened the

once heroic but now vilified Vietminh -- built slowly from the

ground up, on a foundation they had laid over forty years.

Lanky, laid-back Ed Lansdale arrived in Saigon

fresh from having managed a successful anti-Communist

counterinsurgency in the Philippines, where his black bag of dirty

tricks included counterterrorism and the assassination of government

officials who opposed his lackey, Ramon Magsaysay. In the

Philippines his tactics earned him the nickname of the Ugly

American. He brought those tactics to Saigon along with a team of

dedicated Filipino anti-communists who, in the words of one veteran

CIA officer, "would slit their grandmother's throat for a dollar

eighty-five." [10]

In his autobiography, In the Midst of Wars,

Lansdale gives an example of the counterterror tactics he employed

in the Philippines. He tells how one psychological warfare operation

"played upon the popular dread of an asuang, or vampire, to solve a

difficult problem." The problem was that Lansdale wanted government

troops to move out of a village and hunt Communist guerrillas in the

hills, but the local politicians were afraid that if they did, the

guerrillas would

"swoop down on the village and the bigwigs would

be victims." So, writes Lansdale:

A combat psywar [psychological warfare] team was

brought in. It planted stories among town residents of a vampire

living on the hill where the Huks were based.

Two nights later, after giving the stories time

to circulate among Huk sympathizers in the town and make their way

up to the hill camp, the psywar squad set up an ambush along a trail

used by the Huks. When a Huk patrol came along the trail, the

ambushers silently snatched the last man of the patrol, their move

unseen in the dark night. They punctured his neck with two holes,

vampire fashion, held the body up by the heels, drained it of blood,

and put the corpse back on the trail. When the Huks returned to look

for the missing man and found their bloodless comrade, every member

of the patrol believed that the vampire had got him and that one of

them would be next if they remained on the hill.

When daylight came, the whole Huk squadron moved

out of the vicinity. [11]

Lansdale defines the incident as "low humor" and

"an appropriate response ... to the glum and deadly practices of

communists and other authoritarians." [12] And by doing so, former

advertising executive Lansdale -- the merry prankster whom author

Graham Greene dubbed the Quiet American -- came to represent the

hypocrisy of American policy in South Vietnam. For Lansdale used

Madison Avenue language to construct a squeaky- clean, Boy Scout

image, behind which he masked his own perverse delight in atrocity.

In Saigon, Lansdale managed several programs

which were designed to ensure Diem's internal security and which

later evolved and were incorporated into Phoenix. The

process began in July 1954, when, posing as an

assistant Air Force attache to the U.S. Embassy, Lansdale got the

job of resettling nearly one million Catholic refugees from North

Vietnam. As chief of the CIA's Saigon Military Mission, Lansdale

used the exodus to mount operations against North Vietnam. To this

end he hired the Filipino-staffed Freedom Company to train two

paramilitary teams, which, posing as refugee relief organizations

supplied by the CIA-owned airline, Civil Air Transport, activated

stay-behind nets, sabotaged power plants, and spread false rumors of

a Communist bloodbath. In this last regard, a missionary named Tom

Dooley concocted lurid tales of Vietminh soldiers' disemboweling

pregnant Catholic women, castrating priests, and sticking bamboo

slivers in the ears of children so they could not hear the Word of

God.

Dooley's tall tales of terror galvanized American

support for Diem but were uncovered in 1979 during a Vatican

sainthood investigation. [C-1]

From Lansdale's clandestine infiltration and

"black" propaganda program evolved the Vietnamese Special Forces,

the Luc Luong Duc Biet (LLDB). Trained and organized by the CIA, the

LLDB reported directly to the CIA-managed Presidential Survey

Office. As a palace guard, says Kevin Generous in Vietnam: The

Secret War, "they ... were always available for special details

dreamed up by President Diem and his brother Nhu." [13] Those

"special" details sometimes involved "terrorism against political

opponents." [14]

Another Lansdale program was aimed at several

thousand Vietminh stay-behind agents organizing secret cells and

conducting propaganda among the people. As a way of attacking these

agents, Lansdale hired the Freedom Company to activate Operation

Brotherhood, a paramedical team patterned on the typical Special

Forces A team. Under CIA direction, Operation Brotherhood built

dispensaries that were used as cover for covert counterterror

operations. Operation Brotherhood spawned the Eastern Construction

Company, which

provided five hundred hard-core Filipino

anti-Communists who, while building roads and dispensing medicines,

assisted Diem's security forces by identifying and eliminating

Vietminh agents.

In January 1955, using resettled Catholic

refugees trained by the Freedom Company as cadre, Lansdale began his

Civic Action program, the centerpiece of Diem's National Security

program. Organized and funded by the CIA in conjunction with the

Defense Ministry, but administered through the Ministry of Interior

by the province chiefs, Civic Action aimed to do four things: to

induce enemy soldiers to defect; to organize rural people into

self-defense forces to insulate their villages from VC influence; to

create political cadres who would sell the idea that Diem -- not the

Vietminh -- represented national aspirations; and to provide cover

for counterterror. In doing these things, Civil Action cadres

dressed in black pajamas and went into villages to dig latrines,

patch roofs, dispense medicines, and deliver propaganda composed by

Lansdale. In return the people were expected to inform on Vietminh

guerrillas and vote for Diem in the 1956 reunification elections

stipulated by the Geneva Accords.

However, the middle-class northern Catholics sent

to the villages did not speak the same dialect as the people they

were teaching and succeeded only in alienating them. Not only did

Civic Action fail to win the hearts and minds of the rural

Vietnamese, but as a unilateral CIA operation it received only lip

service from Diem and his Can Lao cronies, who, in Lansdale's words,

"were afraid that it was some scheme of mine to flood the country

with secret agents." [15]

On May 10, 1955, Diem formed a new government and

banished the French (who kept eighty thousand troops in the South

until 1956) to outposts along the coast. Diem then appointed Nguyen

Ngoc Le as his first director general of the National Police. A

longtime CIA asset, Le worked with the Freedom Company to organize

the Vietnamese Veterans Legion. As a way of extending Can Lao party

influence, Vietnamese veteran legion posts were

established throughout Vietnam and, with advice

and assistance from the U.S. Information Service, took over the

distribution of all existing newspapers and magazines. The legion

also sponsored the first National Congress, held on May 29, 1955, at

City Hall in Saigon. One month later the Can Lao introduced its

political front, the National Revolution Movement.

On July 16, 1955, knowing the Buddhist population

would vote overwhelmingly for the Vietminh, Diem renounced the

reunification elections required by the Geneva Accords. Instead, he

rigged a hastily called national referendum. Announced on October 6

and held on October 23, the elections, says Professor Huy, "were an

absolute farce. Candidates chosen to be elected had to sign a letter

of resignation in which the date was vacant. In case after the

election the representative was considered undesirable, Nhu had only

to put a date on the letter to have him expelled from the National

Assembly." [16]

Elected president by a vast majority, Diem in

1956 issued Ordinance 57-A. Marketed by Lansdale as agrarian reform,

it replaced the centuries-old custom of village self-government with

councils appointed by district and province chiefs. Diem, of course,

appointed the district chiefs, who appointed the village councils,

which then employed local security forces to collect exorbitant

rents for absentee landlords living the high life in Saigon.

Universal displeasure was the response to

Ordinance 57-A, the cancellation of the reunification elections, and

the rigged election of 1955. Deprived of its chance to win legal

representation, the Vietcong launched a campaign of its own,

emphasizing social and economic awareness. Terror was not one of

their tactics. Says Rand Corporation analyst J. J. Zasloff in

"Origins of the Insurgency in South Vietnam 1954-1960": "There is no

evidence in our interviews that violence and sabotage were part of

their assignment." Rather, communist cadres were told "to return to

their home provinces and were instructed, it appears, to limit their

activities to organizational and

propaganda tasks." [17]

However, on the basis of CIA reports saying

otherwise, Diem initiated the notorious Denunciation of the

Communists campaign in 1956. The campaign was managed by security

committees, which were chaired by CIA-advised security officers who

had authority to arrest, confiscate land from, and summarily execute

Communists. In determining who was a Communist, the security

committees used a three-part classification system: A for dangerous

party members, B for less dangerous party members, and C for loyal

citizens. As happened later in Phoenix, security chiefs used the

threat of an A or B classification to extort from innocent

civilians, while category A and B offenders -- fed by their families

-- were put to work without pay building houses and offices for

government officials.

The military, too, had broad powers to arrest and

jail suspects while on sweeps in rural areas. Non-Communists who

could not afford to pay "taxes" were jailed until their families

came up with the cash. Communists fared worse. Vietminh flags were

burned in public ceremonies, and portable guillotines were dragged

from village to village and used on active and inactive Vietminh

alike. In 1956 in the Central Highlands fourteen thousand people

were arrested without evidence or trial -- people were jailed simply

for having visited a rebel district -- and by year's end there were

an estimated twenty thousand political prisoners nationwide. [18]

In seeking to ensure his internal security

through the denunciation campaign, Diem persecuted the Vietminh and

alienated much of the rural population in the process. But "the most

tragic error," remarks Professor Huy, "was the liquidation of the

Cao Dai, Hoa Hao and Binh Xuyen forces. By destroying them, Diem

weakened the defense of South Vietnam against communism. In fact,

the remnants

... were obliged to join the Vietnamese

Stalinists who were already reinforced by Diem's anti-communist

struggle

campaign.

"Diem's family dealt with this problem," Huy goes

on, "by a repressive policy applied through its secret service. This

organ bore the very innocent name of the Political and Social

Research Service. It was led by Dr. Tran Kim Tuyen, a devoted

Catholic, honest and efficient, who at the beginning sought only to

establish a network of intelligence agents to be used against the

communists. It had in fact obtained some results in this field. But

soon it became a repressive tool to liquidate any opponent." [19]

By then Ed Lansdale had served his purpose and

was being unceremoniously rotated out of Vietnam, leaving behind the

harried Civic Action program to his protege, Rufus Phillips.

Meanwhile, "Other Americans were working closely with the

Vietnamese," Lansdale writes, noting: "Some of the relationships led

to a development which I believed could bring only eventual disaster

to South Vietnam."

"This development was political," Lansdale

observes. "My first inkling came when several families appeared at

my house one morning to tell me about the arrest at midnight of

their men-folk, all of whom were political figures. The arrests had

a strange aspect to them, having come when the city was asleep and

being made by heavily armed men who were identified as 'special

police.'" [20]

Sensing the stupidity of such a program, Lansdale

appealed to Ambassador George Reinhardt, suggesting that "Americans

under his direction who were in regular liaison with Nhu, and who

were advising the special branch of the police, would have to work

harder at influencing the Vietnamese toward a more open and free

political concept." But, Lansdale was told, "a U.S. policy decision

had been made. We Americans were to give what assistance we could to

the building of a strong nationalistic party that would support

Diem. Since Diem was now the elected president, he needed to have

his own party." [21]

"Shocked" that he had been excluded from such a

critical policy decision, Lansdale, to his credit, tried to persuade

Diem to disband the Can Lao. When that failed, he took his case to

the Dulles brothers since they "had decisive voices in determining

the U.S. relationship with South Vietnam." But self-described

"visionary and idealist" Lansdale's views were dismissed

off-handedly by the pragmatic Dulleses in favor "of the one their

political experts in Saigon had recommended." Lansdale was told he

should "disengage myself from any guidance to political parties in

Vietnam." [22]

The mask of democracy would be maintained. But

the ideal was discarded in exchange for internal security.

Librarian's Comment:

[C-1] July 30, 1979 Vol. 12 No. 5 18 Years After

Dr. Tom Dooley's Death, a Priest Insists He Was a Saint, Not a CIA

Spook, By Rosemary Rawson

Tom Dooley was a real taskmaster, and he had an

Irish temper, there's no doubt about that," says the Rev.

Maynard Kegler. "But the documents in no way

imply that he was an agent of the CIA." The papers in question are

recently disclosed agency records that identify Dr. Dooley as a

sometime CIA informant (but not as an actual spy).

They have sparked a new flurry of interest in the

controversial medical missionary—once known as "Dr. America"—whose

work in Laos captured the hearts and minds of his countrymen in the

innocent days before the war in Vietnam. Ultimately, suspicions

about the doctor could torpedo a cause Father Kegler has promoted

for five years—the elevation of Dooley, who died in 1961, to

sainthood in the Roman Catholic Church.

Father Kegler, 54, acted as U.S.-based liaison

between his religious order, the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, and

Dooley from 1958 to 1961. "I spent time with him in this country,

not in Laos," says Kegler, "and got to know him

well." After Dooley's death from cancer, Kegler,

now director of a Buffalo, Minn. retreat house, began the research

that would enable him to argue the case for Dooley's beatification.

It is the first step in the complex process of attaining sainthood.

Kegler claims he was not surprised when his

investigation led him to the CIA. There he found 500 unclassified

documents showing that Dooley occasionally helped the agency and

that it kept a close watch on him. "He gave them information out of

patriotism, love of country and all that the United States stood for

in 1958," Kegler insists. "He was willing to do that in return for

having a little more freedom to do his work and a little less

harassment. But he didn't initiate contact with the CIA, and he took

no money for his work."

Nonetheless, Dooley's reputation has taken a

beating in recent years from critics on both the left and the right.

In the '60s antiwar activists came to regard his brand of self-

righteous anti-Communism as one of the causes of U.S. intervention

in Vietnam. Others have dismissed him as an aggressive

self-publicist who practiced ineffective "hit- and-run" medicine. A

fund set up to continue Dooley's work after his death went bankrupt,

and the man who succeeded him in Laos died by his own hand.

Father Kegler, however, believes Dooley has been

maligned. "All of the people I have interviewed who knew Tom

personally have been very positive," he reports. "The negative

response was all from people who never knew him and never worked

with him." As evidence of Dooley's sanctity, the priest cites his

decision, while a Navy surgeon, to devote his life to Indochina.

"When he saw the plight of those hundreds of thousands of people,"

Kegler reports, "he said, 'My God, I can't go home and leave them.'

Up until that time I believe Tom Dooley was just an ordinary

Christian—maybe not even that." The priest is equally impressed with

Dooley's courage in fighting his cancer. "The example he gave while

facing suffering, facing death, was a great service to the American

people," says his sponsor. "Cancer is the greatest fear in the

country today."

Kegler's quest to establish Dooley's sainthood—

technically, church certification that a dead person is now in

heaven—is far from over. He may possibly have to prove that Dooley

is responsible for two certifiable miracles, then must submit his

entire case to Vatican- appointed "devil's advocates" who will

attempt to pick it apart. Kegler remains confident. "When we

interpret Tom Dooley's actions in Laos, we have to do it in the

context of what he knew of the CIA at the time," he concludes. "In

no way will this connection hurt his cause for sainthood—in fact, I

think it's going to help it."

CHAPTER 2: Internal Security

In 1954, in the professed belief that it ought to

extend the "American way" abroad, Michigan State University (MSU)

offered to provide the government of Vietnam with a huge technical

assistance program in four areas: public information, public

administration, finance and economics, and police and security

services. The contract was approved in early 1955, shortly after the

National Security Council (NSC) had endorsed Diem, and over the next

seven years MSU's Police Administration Division spent fifteen

million dollars of U.S. taxpayers' money building up the GVN's

internal security programs. In exchange for the lucrative contract,

the Michigan State University Group (MSUG) became the vehicle

through which the CIA secretly managed the South Vietnamese "special

police."

MSUG's Police Administration Division contributed

to Diem's internal security primarily by reorganizing his police and

security forces. First, Binh Xuyen gangsters in the Saigon police

were replaced with "good cops" from the Surete. Next, recruits from

the Surete were inducted into the Secret Service, Civil Guard, and

Military Security Service (MSS), which was formed by Ed Lansdale in

1954 as "military coup insurance." On administrative matters the MSS

reported to the Directorate of Political Warfare in liaison with the

CIA, while its operations staff reported to the Republic of Vietnam

Armed Forces (RVNAF)'s Joint General Staff in liaison with MAAG

counterintelligence officers. All general directors of police and

security services were military officers.

The Surete (plainclothesmen handling

investigations, customs, immigration, and revenue) was renamed the

Vietnamese Bureau of Investigations (VBI) and combined with the

municipal police (uniformed police in twenty-two autonomous cities

and Saigon) into a General Directorate of Police and Security

Services within the Ministry of the Interior. This early attempt at

bureaucratic streamlining was undermined by Diem, however, who kept

the various police and security agencies spying on one another. Diem

was especially wary of the VBI, which as the Surete had faithfully

served the French and which, after 1954, under CIA management, was

beyond his control. As a result, Diem judged the VBI by the extent

to which it attacked his domestic foes, spied on the Military

Security Service, and kept province chiefs in line.

Because it managed the central records

depository, the VBI was the most powerful security force and

received the lion's share of American "technical" aid. While other

services got rusty weapons, the VBI got riot guns, bulletproof

vests, gas masks, lie detectors, a high-command school, a modern

crime lab and modern interrogation centers; and the most promising

VBI officers were trained by the CIA and FBI at the International

Police Academy at Georgetown University in agent handling, criminal

investigations, interrogation, and counterinsurgency. The VBI (the

Cong An to Vietnamese) is one of the two foundation stones of

Phoenix.

Whereas the majority of Michigan State's police

advisers were former state troopers or big-city detectives, the men

who advised the VBI and trained Diem's Secret Service were CIA

officers working under cover as professors in the Michigan State

University Group. Each morning myopic MSUG employees watched from

their quarters across the street as senior VBI adviser Raymond

Babineau and his team went to work at the National Police

Interrogation Center, which, Graham Greene writes in The Quiet

American, "seemed to smell of urine and injustice." [1] Later in the

day the MSUG contingent watched while truckloads of political

prisoners -- mostly old men, women, and children arrested the night

before -- were handcuffed and carted off to Con Son Prison.

America's first colonialists in Saigon looked, then looked away. For

four years they dared not denounce the mass arrests or the fact that

room P-40 in the Saigon Zoo was used as a morgue and torture

chamber. No one wanted to incriminate himself or get on the wrong

side of Babineau and his proteges in the "special police."

The fear was palpable. In his book War Comes to

Long An, Jeffrey Race quotes a province chief: "I hardly ever dared

to look around in the office with all the Can Lao people there

watching me, and in those days it was just impossible to resign --

many others had tried -- they were just led off in the middle of the

night by Diem's men dressed as VC, taken to P-40 or Poulo Condore

[Con Son Prison] and never heard from again." [2]

While the VBI existed primarily to suppress

Diem's domestic opponents, it also served the CIA by producing an

annual Ban Tran Liet Viet Cong (Vietcong order of battle). Compiled

for the most part from notes taken by secret agents infiltrated into

VC meetings, then assembled by hand at the central records

depository, the Ban Tran Liet was the CIA's biography of the VCI and

the basis of its anti-infrastructure operations until 1964.

In 1959 Diem held another sham election. Said one

Vietnamese official quoted by Race: "The 1959 election was very

dishonest. Information and Civic Action Cadre went around at noon

when everyone was home napping and stuffed ballot boxes. If the

results didn't come out right they were adjusted at district

headquarters." When asked if anyone complained, the official

replied, "Everyone was terrified of the government

The Cong An beat people and used 'the water

treatment.' But there was nothing anyone could

do. Everyone was terrified." Said another official: "During the Diem

period the people here saw the government was no good at all. That

is why 80% of them followed the VC. I was the village chief then,

but I had to do what the government told me. If not, the secret

police [VBI] would have me picked up and tortured me to death. Thus

I was the very one who rigged the elections here." [3]

As is apparent, Diem's security forces terrorized

the Vietnamese people more than the VCI. In fact, as Zasloff noted

earlier, prior to 1959 the VCI carried out an official policy of

nonviolence. "By adopting an almost entirely defensive role during

this period," Race explains, "and by allowing the government to be

the first to employ violence, the Party -- at great cost -- allowed

the government to pursue the conflict in increasingly violent terms,

through its relentless reprisal against any opposition, its use of

torture, and, particularly after May 1959, through the psychological

impact in the rural areas of the proclamation of Law 10/59." [4]

In Phoenix/Phung Hoang: A Study of Wartime

Intelligence Management, CIA officer Ralph Johnson calls the 10/59

Law "the GVN's most serious mistake." Under its provisions, anyone

convicted of "acts of sabotage" or "infringements on the national

security" could be sentenced to death or life imprisonment with no

appeal. Making matters worse, Johnson writes, was the fact that 'The

primary GVN targets were former Viet Minh guerrillas -- many of whom

were nationalists, not Communists -- regardless of whether or not

they were known to have been participating in subversive

activities."' The 10/59 Law resulted in the jailing of fifty

thousand political prisoners by year's end. But rather than suppress

the insurgency, Vietnamese from all walks of life joined the cause.

Vietminh cadres moved into the villages from secluded base camps in

the Central Highlands, the Rung Sat, the Ca Mau swamps, and the

Plain of Reeds. And after four years of Diem style democracy, the

rural population welcomed them with open arms.

The nonviolence policy practiced by Vietcong

changed abruptly in 1959, when in response to the 10/59 Law and CIA

intrusions into North Vietnam, the Lao Dong Central Committee

organized the 559th Transportation and Support Group. Known as Doan

559, this combat-engineer corps carved out the Ho Chi Minh Trail

through the rugged mountains and fever-ridden jungles of South

Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

Doan 559 paved the way for those Vietminh

veterans who had gone North in 1954 and returned in 1959 to organize

self-defense groups and political cells in Communist- controlled

villages. By the end of 1959 Doan 559 had infiltrated forty-five

hundred regroupees back into South Vietnam.

Sent to stop Doan 559 from infiltrating troops

into South Vietnam were U.S. Army Special Forces commandos trained

in "behind-the-lines" anti-guerrilla and intelligence-gathering

operations. Working in twelve-member A teams under cover of Civic

Action, the Green Berets organized paramilitary units in remote

rural regions and SWAT team-type security forces in cities. In

return, they were allowed to occupy strategic locations and

influence political events in their host countries.

Developed as a way of fighting cost effective

counterinsurgencies, the rough-and- tumble Green Berets were an

adjunct of the CIA -- which made them a threat to the U.S. Army. But

Special Forces troopers on temporary duty (TDY) could go places

where the Geneva Accords restricted the number of regular soldiers.

For example, in Laos, the "Sneaky Petes" wore civilian clothes and

worked in groups of two or three, turning Pathet Lao deserters into

double agents who returned to their former units with electronic

tracking devices, enabling the CIA to launch air attacks against

them. Other double agents returned to their units to lead them into

ambushes. As Ed Lansdale explains, once inside enemy ranks, "they

could not only collect information for passing secretly to the

government but also could work to induce the rank and file to

surrender." Volunteers for such "risky business," Lansdale adds,

were trained singly or in groups as large as companies that were

"able to get close enough in their disguise for surprise combat,

often hand to hand." [6]

By the late 1950s, increasing numbers of American

Special Forces were in South Vietnam, practicing the terrifying

black art of psychological warfare.

***

Arriving in Saigon in the spring of 1959 as the

CIA's deputy chief of station was William Colby. An OSS veteran,

Princeton graduate, liberal lawyer, and devout Catholic, Colby

managed the station's paramilitary operations against North Vietnam

and the Vietcong. He also managed its political operations and

oversaw deep-cover case officers like Air America executive Clyde

Bauer, who brought to South Vietnam its Foreign Relations Council,

Chamber of Commerce, and Lions' Club, in Bauer's

words, "to create a strong civil base." [7] CIA

officers under Colby's direction funneled money to all political

parties, including the Lao Dong, as a way of establishing long-range

penetration agents who could monitor and manipulate political

developments.

Under Colby's direction, the CIA increased its

advice and assistance to the GVN's security forces, at the same time

that MSUG ceased being a CIA cover. MSUG advisers ranging across

South Vietnam, conducting studies and reporting on village life, had

found themselves stumbling over secret policemen posing as village

chiefs and CIA officers masquerading as anthropologists. And even

though these ploys helped security forces catch those in the VCI,

they also put the MSUG advisers squarely between Vietcong cross

hairs.

So it was that while Raymond Babineau was on

vacation, assistant MSUG project chief Robert Scigliano booted the

VBI advisory unit out from under MSUG cover. The State Department

quickly absorbed the CIA officers and placed them under the Agency

for International Development's Public Safety Division (AID/PSD),

itself created by CIA officer Byron Engel in 1954 to provide

"technical assistance" and training to police and security officials

in fifty-two countries. In Saigon in 1959, AID/PSD was managed by a

former Los Angeles policeman, Frank Walton, and its field offices

were directed by the CIA-managed Combined Studies Group, which

funded cadres and hired advisers for the VBI, Civil Guard, and

Municipal police.

Through AID/PSD, technical assistance to police

and security services increased exponentially. Introduced were a

telecommunications center; a national police training center at Vung

Tau; a rehabilitation system for defecting Communists which led to

their voluntary service in CIA security programs; and an

FBI-sponsored national identification registration program, which

issued ID cards to all Vietnamese citizens over age fourteen as a

means of identifying Communists, deserters, and fugitives.

Several other major changes occurred at this

juncture. On the assumption that someday the Communists would be

defeated, MSUG in 1957 had reduced the Civil Guard in strength and

converted it into a national police constabulary, which served

primarily as a security force for district and province chiefs (all

of whom were military officers after 1959) and also guarded bridges,

major roads, and power stations. CIA advisers assigned to the

constabulary developed clandestine cells within its better units.

Operating out of police barracks at night in civilian clothes, these

ragtag Red Squads were targeted against the VCI, using intelligence

provided by the VBI. However, in December 1960 the U.S. Military

Assistance Advisory Group seized control of the constabulary and

began organizing it into company, battalion, and regimental units

armed with automatic rifles and machine guns. The constabulary was

renamed the Regional Forces and placed under the Ministry of

Defense. The remaining eighteen thousand rural policemen thereafter

served to enforce curfews and maintain law and order in agrovilles

-- garrison communities consisting of forcefully relocated persons,

developed by MSUG in 1959 in response to Ed Lansdale's failed Civic

Action program.

With the demise of Civic Action teams,

pacification efforts were by default dumped on the Vietnamese Army,

whose heavy-handed tactics further alienated the rural Vietnamese