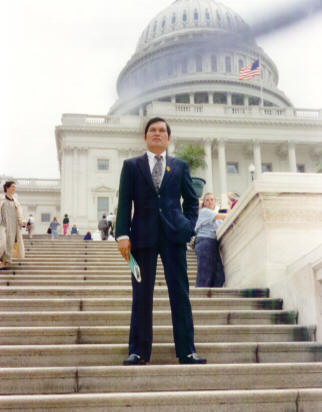

at Capitol. June 19.1996

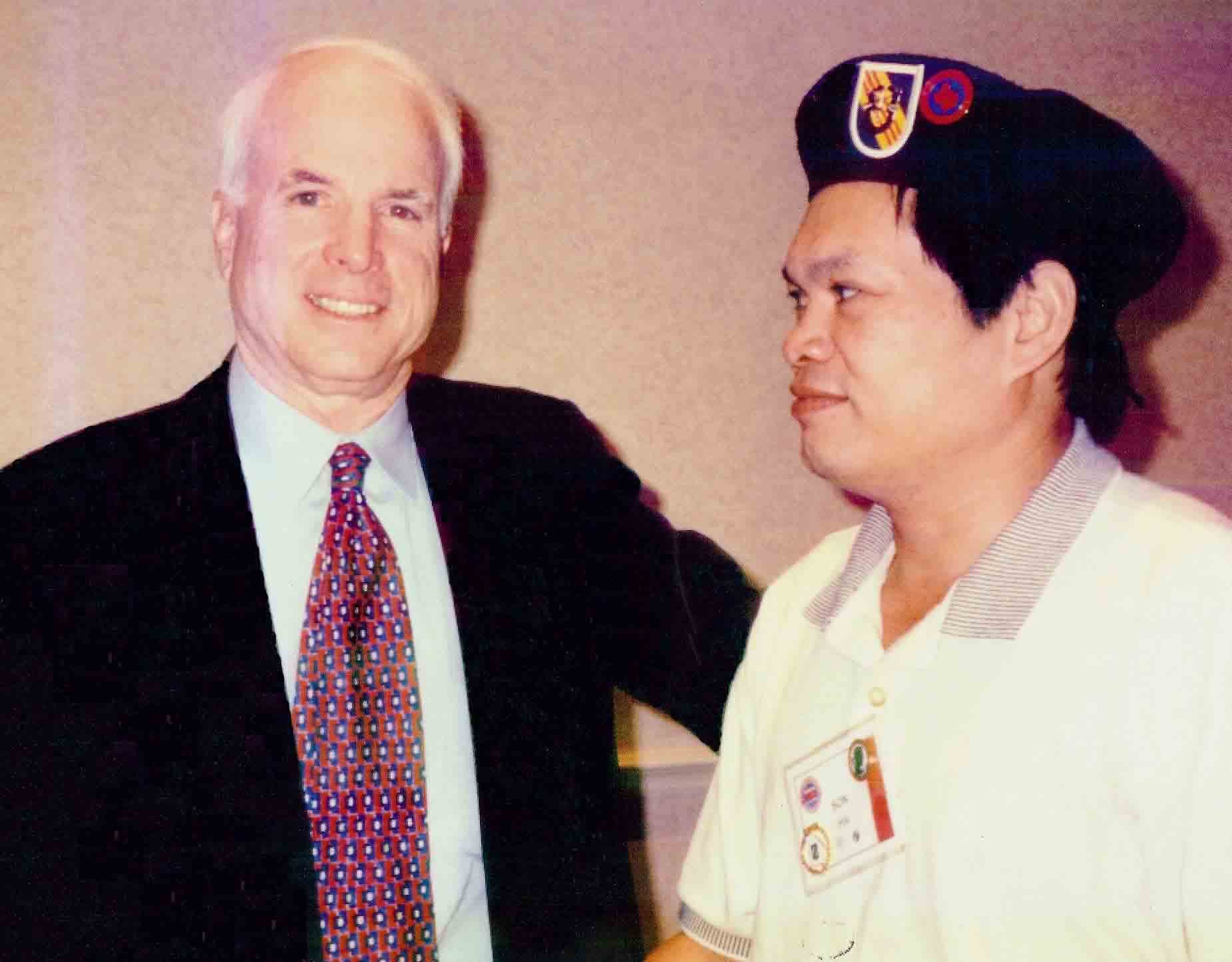

with Sen. JohnMc Cain

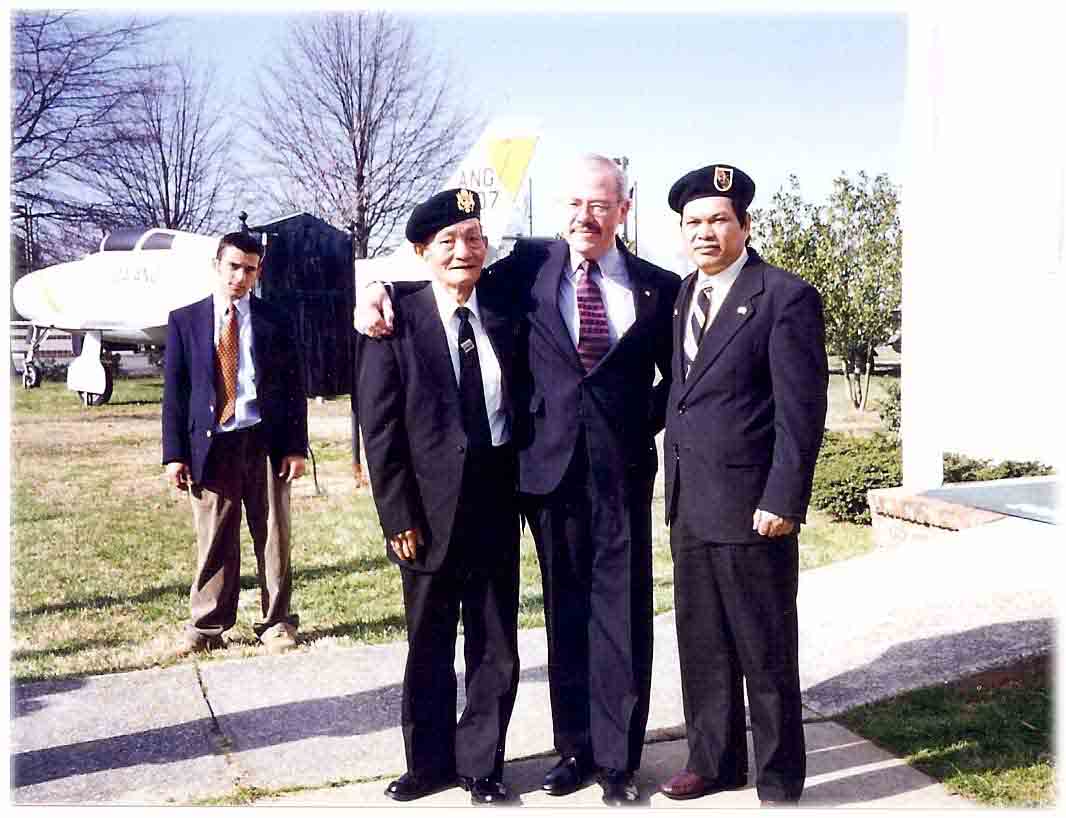

with General John K Singlaub

CNBC .Fox .FoxAtl .. CFR. CBS .CNN .VTV.

.WhiteHouse .NationalArchives .FedReBank

.Fed Register .Congr Record .History .CBO

.US Gov .CongRecord .C-SPAN .CFR .RedState

.VideosLibrary .NationalPriProject .Verge .Fee

.JudicialWatch .FRUS .WorldTribune .Slate

.Conspiracy .GloPolicy .Energy .CDP .Archive

.AkdartvInvestors .DeepState .ScieceDirect

.NatReview .Hill .Dailly .StateNation .WND

-RealClearPolitics .Zegnet .LawNews .NYPost

.SourceIntel .Intelnews .QZ .NewAme

.GloSec .GloIntel .GloResearch .GloPolitics

.Infowar .TownHall .Commieblaster .EXAMINER

.MediaBFCheck .FactReport .PolitiFact .IDEAL

.MediaCheck .Fact .Snopes .MediaMatters

.Diplomat .NEWSLINK .Newsweek .Salon

.OpenSecret .Sunlight .Pol Critique .

.N.W.Order .Illuminatti News.GlobalElite

.NewMax .CNS .DailyStorm .F.Policy .Whale

.Observe .Ame Progress .Fai .City .BusInsider

.Guardian .Political Insider .Law .Media .Above

.SourWatch .Wikileaks .Federalist .Ramussen

.Online Books .BREIBART.INTERCEIPT.PRWatch

.AmFreePress .Politico .Atlantic .PBS .WSWS

.NPRadio .ForeignTrade .Brookings .WTimes

.FAS .Millenium .Investors .ZeroHedge .DailySign

.Propublica .Inter Investigate .Intelligent Media

.Russia News .Tass Defense .Russia Militaty

.Scien&Tech .ACLU .Veteran .Gateway. DeepState

.Open Culture .Syndicate .Capital .Commodity

.DeepStateJournal .Create .Research .XinHua

.Nghiên Cứu QT .NCBiển Đông .Triết Chính Trị

.TVQG1 .TVQG .TVPG .BKVN .TVHoa Sen

.Ca Dao .HVCông Dân .HVNG .DấuHiệuThờiĐại

.BảoTàngLS.NghiênCứuLS .Nhân Quyền.Sài Gòn Báo

.Thời Đại.Văn Hiến .Sách Hiếm.Hợp Lưu

.Sức Khỏe .Vatican .Catholic .TS KhoaHọc

.KH.TV .Đại Kỷ Nguyên .Tinh Hoa .Danh Ngôn

.Viễn Đông .Người Việt.Việt Báo.Quán Văn

.TCCS .Việt Thức .Việt List .Việt Mỹ .Xây Dựng

.Phi Dũng .Hoa Vô Ưu.ChúngTa .Eurasia.

CaliToday .NVR .Phê Bình . TriThucVN

.Việt Luận .Nam Úc .Người Dân .Buddhism

.Tiền Phong .Xã Luận .VTV .HTV .Trí Thức

.Dân Trí .Tuổi Trẻ .Express .Tấm Gương

.Lao Động .Thanh Niên .Tiền Phong .MTG

.Echo .Sài Gòn .Luật Khoa .Văn Nghệ .SOTT

.ĐCS .Bắc Bộ Phủ .Ng.TDũng .Ba Sàm .CafeVN

.Văn Học .Điện Ảnh .VTC .Cục Lưu Trữ .SoHa

.ST/HTV .Thống Kê .Điều Ngự .VNM .Bình Dân

.Đà Lạt * Vấn Đề * Kẻ Sĩ * Lịch Sử *.Trái Chiều

.Tác Phẩm * Khào Cứu * Dịch Thuật * Tự Điển *

KIM ÂU -CHÍNHNGHĨA -TINH HOA - STKIM ÂU

CHÍNHNGHĨA MEDIA-VIETNAMESE COMMANDOS

BIÊTKÍCH -STATENATION - LƯUTRỮ -VIDEO/TV

DICTIONAIRIES -TÁCGỈA-TÁCPHẨM - BÁOCHÍ . WORLD - KHẢOCỨU - DỊCHTHUẬT -TỰĐIỂN -THAM KHẢO - VĂNHỌC - MỤCLỤC-POPULATION - WBANK - BNG ARCHIVES - POPMEC- POPSCIENCE - CONSTITUTION

VẤN ĐỀ - LÀMSAO - USFACT- POP - FDA EXPRESS. LAWFARE .WATCHDOG- THỜI THẾ - EIR.

ĐẶC BIỆT

-

The Invisible Government Dan Moot

-

The Invisible Government David Wise

ADVERTISEMENT

Le Monde -France24. Liberation- Center for Strategic- Sputnik

https://www.intelligencesquaredus.org/

Space - NASA - Space News - Nasa Flight - Children Defense

Pokemon.Game Info. Bách Việt Lĩnh Nam.US Histor. Insider

World History - Global Times - Conspiracy - Banking - Sciences

World Timeline - EpochViet - Asian Report - State Government

https://lens.monash.edu/@politics-society/2022/08/19/1384992/much-azov-about-nothing-how-the-ukrainian-neo-nazis-canard-fooled-the-world

with General Micheal Ryan

DEBT CLOCK . WORLMETERS . TRÍ TUỆ MỸ . SCHOLARSCIRCLE. CENSUS - SCIENTIFIC - COVERT- CBO - EPOCH ĐKN - REALVOICE -JUSTNEWS- NEWSMAX - BREIBART - REDSTATE - PJMEDIA - EPV - REUTERS - AP - NTD - REPUBLIC TTV - BBC - VOA - RFI - RFA - HOUSE - TỬ VI - VTV- HTV - PLUS - TTRE - VTX - SOHA -TN - CHINA - SINHUA - FOXNATION - FOXNEWS - NBC - ESPN - SPORT - ABC- LEARNING - IMEDIA -NEWSLINK - WHITEHOUSE- CONGRESS -FED REGISTER -OAN DIỄN ĐÀN - UPI - IRAN - DUTCH - FRANCE 24 - MOSCOW - INDIA - NEWSNOW- NEEDTOKNOW NEWSPUNCH - CDC - WHO BLOOMBERG - WORLDTRIBUNE - WND - MSNBC- REALCLEAR - PBS - SCIENCE - HUMAN EVENT - TABLET - AMAC - WSWS PROPUBICA -INVESTOPI-CONVERSATION - BALANCE - QUORA - FIREPOWER GLOBAL- NDTV- ALJAZEER- TASS- DAWN NATURAL- PEOPLE- BRIGHTEON - CITY JOURNAL- EUGENIC- 21CENTURY - PULLMAN- SPUTNIK- COMPACT - DNYUZ- CNA

NIK- JAP- SCMP- CND- JAN- JTO-VOE- ASIA- BRIEF- ECNS-TUFTS- DIPLOMAT- JUSTSECU- SPENDING- FAS - GWINNETT JAKARTA -- KYO- CHIA - HARVARD - INDIATO - LOTUS- CONSORTIUM - COUNTERPUNCH- POYNTER- BULLETIN - CHI DAILY

Beyond Marxism? The ‘Crisis of Marxism’ and the Post-Marxist Moment

Stathis Kouvelakis

Forthcoming In Alex Callinicos, Stathis

Kouvelakis, Lucia Pradella (eds.), Handbook of Marxism and

Postmarxism, Routledge, 2020

Two centuries after his

birth, Marx’s image in the mainstream media and academic circles can

be summed up by the motto “Marx is alive but Marxism is dead”. The

Marx who is still alive is usually presented as an “economist” who

provided a lucid view of capitalism and of its internal

contradictions. This view has periodically re-emerged in the decades

that followed the collapse of the Soviet bloc: each time a crisis

breaks out, representatives of the mainstream confess that somehow

“Marx was right”, or, at least, more lucid than those economists

who, once more, have proved unable to foresee the coming crisis and

its long-term effects in contemporary societies. Thus, shortly after

the start of the 2008 recession, Nouriel Roubini, a senior economist

for the Clinton administration, the IMF and the World Bank, declared

to the

Wall Street Journal:

“Karl Marx had it right. At some point, capitalism can destroy

itself” (Roubini 2011). More recently, commenting on the impact of

new digital technologies, the Bank of England governor Mark Carney

said that “we have exactly the same dynamics as existed 150 years

ago – when Karl Marx was scribbling the

Communist Manifesto” (Drury

2018). Debatable as they might be in terms of their analytical

value, such statements reveal however that the idea of a structural

contradiction within capitalism still seems inseparable from the

name of the author of

Capital.

The unexpected

international success of the French economist Thomas Piketty’s book

Capital in the Twenty-first Century

(Piketty 2014) is a deeper symptom of the impact of the Great

Recession on mainstream public opinion. Piketty, a self-avowedly

non-Marxist supporter of social-democracy, demonstrates with a

wealth of empirical data a tendency to the concentration of wealth

that is inherent to the “normal” functioning of capitalism. The

tendential divergence between the rate of return to capital and the

rate of growth leads to social polarization if the state doesn’t

intervene, via taxation, to attenuate the effects of the

accumulation of assets at the top of the social ladder. By

contesting the belief in the progressive character of this system, a

cornerstone of bourgeois common sense since Bernard Mandeville and

Adam Smith, this approach raises an even more serious challenge to

the legitimacy of the system than the simple recognition of the

inevitability of crises.

Piketty’s conclusion is

that taxing wealth is necessary to avoid the economic and social

instability fuelled by the polarization within advanced Western

societies between a tiny minority of asset-owners and the working

majority. What in previous circumstances would look like a moderate

social-democratic redistributionist proposal, and indeed considered

as such by Piketty’s critics from the left (Duménil and Lévy 2014,

Duménil and Lévy 2015, Lordon 2015), proved nevertheless sufficient

for the defenders of neoliberal orthodoxy to make its author appear

as a “modern Marx” (The Economist

2014). It is true that, despite Piketty’s firm denial of any Marxian

or Marxist influence (Chotiner 2014), the title of the book, as well

as its length and long-term historical perspective, indicates at

least an implicit ambition to compete with the 19th

century German thinker. Its success – nearly three million copies

sold worldwide – resonated strongly with the anti-inequality agenda

put forward by the Occupy movement. It confirmed the loss of

legitimacy of neoliberalism in the very area in which it has most

successfully captured the public mind in its heyday.

The paradox of this

renewed acceptance of Marx’s vision of capitalism is that it goes

together with an almost consensual rejection of any version of the

political project defended by its author. The reasons are all too

obvious: the collapse of the regimes that claimed his legacy

combined with the turn towards a national but nevertheless ruthless

form of capitalism where parties claiming to be “communist” are

still in power – with Cuba standing (temporarily?) as a solitary

exception. The weekly

Die Zeit, Germany’s most

serious outlet of the liberal left, summed up this common sense of

the time in its dossier published under the characteristic title

“Hatte Marx doch recht?” (Was Marx right?). The guiding line was

that “despite all the new enthusiasm for Marx, history teaches that

his dream of the overthrow of circumstances in reality ended

catastrophically. For the working class, it usually turned out badly

when it brought about the revolution. In the Russia of Lenin and

Stalin, in Cuba or, in this century, in Venezuela. In China, too,

workers first had to suffer hard and pay millions in their lives

before the market opened their doors” (Nienhaus 2017).

Still, according to the same publicist, Marx might prove

useful even at a political level by providing capitalism with a

brake on its own self-destructive tendency, which the rising forces

of right-wing “populism” can only reinforce:

It

becomes more pleasant for all when the establishment reacts in fear

of the masses’ revenge. After the world wars of the 20th

century, many countries discovered a way to redistribute the profits

of capitalism, harnessing its power to make it usable for everyone:

the interventionist state. So far, nations have resisted the

tendency of capitalism to self-destruction. But today, a remarkably

high number of people are withdrawing from the system: managers,

financial jugglers, politicians. Marx would have unmasked as a sham

America’s current turn to protectionism. The world should still make

an effort to continue to discredit Marx, the revolutionary

predictor. To do that, one should necessarily read Marx, the

analyst, and Marx, the world economist (Nienhaus 2017).

The reference to Marx in

the current mainstream discourse thus testifies its own internal

contradiction: the perception of capitalism’s structural

deficiencies, the loss of legitimacy of the policies implemented

since the Reagan-Thatcher era – even in the eyes of some fractions

of the elite – only strengthen the belief in the insuperable

character of the system. The ultimate proof lies in the fact that

the only conceivable usefulness of the most radical critique ever

launched against this system is to prevent its “self-destruction”,

i.e. to serve its perpetuation. Even left social scientists such as

Wolfgang Streeck, a sociologist of Weberian inspiration, cannot see

any alternative to the current state of crisis. His notion of an

“end of capitalism” points exactly to this situation: an endless

Götterdämmerung

of capitalism during which it goes down a path of continuous decay

with no solution in sight (Streeck 2016 57-58). This situation,

according to Streeck, derives from a structural factor, i.e. the

capacity of a globalized and finance-dominated capitalism to prevent

the emergence of forces able to challenge the system as such. His

conclusion takes the form of an aporia: although the question of an

alternative to capitalism, and not simply of a better “variety” of

it, should be left open, there seems to be no effective agency

capable of taking on such an endeavour (Streeck 2016, 235).

The “Crisis of Marxism”

This pervasive pessimism

could be interpreted as a consequence of the collapse of Soviet

communism, a dark variant of the (in)famous “end of History” thesis

formulated by Francis Fukuyama in the immediate aftermath of the

event. A longer-term historical perspective shows however that the

aporia of the “desirable yet impossible alternative” significantly

predates the demise of “really existing socialism”. Even more

interestingly, it came from within Marxism and was formulated by

some of the main protagonists of the theoretical debates of the

1960s and 1970. In November 1977, at a conference organized by the

Italian dissident communist daily

Il manifesto, its director

Rossana Rossanda declared in her opening statement that “the very

idea of socialism, not as a generic aspiration but as a theory of

society, a different mode of organization of human existence, is

fading from view” (Rossanda 1977). According to Rossanda, this

crisis of the perspectives of the labour movement “goes beyond the

purely political domain and invests the realm of theory itself. It

is a crisis of Marxism, of which the nouveaux

philosophes are the

caricature, but which is experienced by immense masses as an

unacknowledged reality. Marxism – not as a body of theoretical or

philosophical thought, but as the great idealistic force that was

changing the world – is now groaning under the weight of this this

history”. However, for her, “whatever the nature of the

post-revolutionary societies [of ‘really existing socialism’], they

can and must be interpreted and that Marxism offers a reliable

instrument for doing this.” To be up to this task, Marxism needs to

understand that “the Gulag is the product neither of a philosophy

nor of a pure idea of power and politics”. Hence the necessity to

analyse the economic and social processes that unfolded in the years

following the October revolution, instead of recycling the abstract

debates on the Leninist party and on “relation between the vanguard

and the masses.”

In his own intervention, which became the most

famous of this conference, Louis Althusser confirmed Rossanda’s

diagnosis of the conjuncture while offering a much darker view of

the capacity of Marxism to overcome its crisis. For him, “something

has ‘snapped’ in the history of the labour movement between its past

and present, something which makes its future unsure” (Althusser

1977). This rupture is referred to the fact that “there no longer

exists in the minds of the masses any ‘achieved ideal,’ any really

living reference for socialism.” The “crisis of Marxism” originates

in the Stalinist era, during which

Marxism was entrenched into a series of ossified formulae, but

Stalinism also blocked it insofar as it seemed able to provide

practical solutions and build “socialism in one country,” eventually

extending it to an entire geopolitical bloc.

However, contrary to Rossanda, the French

philosopher seems more than doubtful concerning the capacity of

Marxism to “provid[e]

a really satisfactory... explanation of a history which was, after

all, made in [its] name” – “almost an impossibility” as he states

it. The reason for that lies ultimately within Marxism, and cannot,

as suggested by Rossanda, be resolved by the study of historical

conjunctures in the light of Marxist categories. In 1973, in his

first – and very belated – attempt to provide an explanation for

this phenomenon, Althusser had characterized Stalinism as an

essentially

theoretical

“deviation” which should be analysed as the “posthumous revenge of

the Second International, as a revival of its main tendency”, that

is as a “special form” of “economism” (Althusser 1976, 89). Four

years later, the roots of the problem are located in the writings of

Marx, Lenin and Gramsci. The previous self-confident affirmations on

Marxism as the “new science of the continent History” (Althusser

1971, 15) gives way to the enumeration of a seemingly endless series

of “gaps” and “enigmas”. The theoretical unity of

Capital is seen as “largely

fictitious” and its theory of exploitation suspected of carrying a

“restrictive conception… hindering the broadening of the forms of

the whole working class and people’s struggle” (Althusser 1977). The

status of philosophy and of dialectics in Marx is an “enigma”, as is

his relation to Hegel. No theory of the state, nor of the workers

organisations is to be found in Marx, Lenin or in the entire

“Marxist heritage”. Gramsci’s attempt to fill those gaps with the

“little equations” of the

Prison Notebooks on hegemony

(as a combination of force and consent) just sound “pathetic”.

This systematic demolition makes the statements on the “crisis of

Marxism” as a moment of “possible liberation and renewal” appear as

purely rhetorical. In a private letter sent a few months later to

his friend Merab Mamardachvili, Althusser refers to his intervention

at the Venice conference as a “masked talk”, a desperate attempt to

“dyke up the waters somewhat” (Althusser 2006, 3). He discounts his

own work as nothing more than

“a little, typically French justification, in a

neat little rationalism bolstered with a few references (Cavaillès,

Bachelard, Canguilhem, and, behind them, a bit of the Spinoza-Hegel

tradition), for Marxism's (historical materialism's) pretension to

being a science” (Althusser

2006, 3).

He also confesses that he’s tempted by a definitive retreat to

silence, since what he could work on is “nothing of importance in a

time when one must be armed with enough concrete knowledge in order

to be able to speak of things like the state, the economic crisis,

organisations, the ‘socialist’ countries, etc. I don’t have this

knowledge and I have to, like Marx in 1852, ‘begin again at the

beginning,’ but it’s late for this, given my age, fatigue,

lassitude, and also solitude” (Althusser 2006, 5).

This “radical loss

of morale”, to quote Perry Anderson’s words (Anderson 1983, 29),

should not be seen as an individual case – despite the highly tragic

dimension of Althusser’s destiny – but rather as a symptom of an

epochal turn in the conjuncture. The course of events showed that

Althusser and those who spoke of the “general crisis of Marxism”

(Haider and King 2017) had foreseen the downturn of the

revolutionary energies more clearly than those who, like Anderson,

saw it as a phenomenon “confined to Latin Europe”, essentially

caused by the defeat of the Eurocommunist strategy pursued by the

local Communist parties and supported by most of the Marxist

intelligentsia of those countries (Anderson, 1983 76-77). The

inglorious collapse of the Eastern European “really existing

socialism,” followed by the meltdown of the Western Communist

parties, the turn to capitalism of the Third World “socialist” or

“non-aligned” regimes (first and foremost of China) and the

accelerated integration of social-democracy in the neoliberal order,

signalled the end of the historical cycle initiated by the October

revolution. The idea of Marxism as a reflective form of unity of

revolutionary theory and praxis, and of communism as the “real

movement which abolishes the present state of things”, as Marx and

Engels famously put it in the

German Ideology (CW

5: 49), became more problematic than ever before. The “crisis of

Marxism” was over, leaving the future perspective of Marxism in a

state of radical uncertainty.

The “Post-Marxist” Moment

In a way, Anderson’s

judgment castigating “the veritable

débandade of so many leading

French thinkers of the Left since 1976” (Anderson 1983 32) has been

vindicated. Indeed, unlike its predecessor of the late 19th-early

20th

century, sparked by the controversy around Eduard Bernstein’s

“revisionism”, the late 20th

century “crisis of Marxism” produced little of significance compared

to the controversies which made Marxism a living tradition

throughout its history (Kouvelakis 2008a). In his 1983 essay,

Anderson had already pointed out that what Marxism in crisis shared

with its predecessor (“Western Marxism” in the Andersonian

terminology) was the “poverty of strategy” (Anderson 1983, 28). More

recently, Daniel Bensaïd elaborated on the “eclipse of strategic

reason” as the central dimension of Marxism’s retreat from the 1980s

onwards (Bensaïd 2007). What now appears clear is that the

definitive collapse of Marxist “orthodoxy” – which only survives as

a farcical pastiche in the institutes of the Chinese CP – also led

to the dislocation of the various forms of “heterodoxy”, if not as

purely intellectual arguments at least as forces capable of

intervening in the course of events.

Let’s pursue the

comparison between the two “fin-de-siècle” crises of Marxism a bit

further. The late 19th

century “revisionist” attack on the official doctrine of German

Social Democracy – the model party of the entire international

socialist movement – triggered a high-profile debate on the nature

of the transformations of contemporary capitalism, the validity of

the

Zusammenbruchstheorie

(“breakdown theory”) as the cornerstone of the “orthodox” strategy,

the evolution of class structure in Western societies, the role of

mass action, cooperatives, reforms and elections. These were the

issues on which Bernstein, Hilferding, Kautsky, Labriola, Luxemburg,

Sorel and many others (including major non-Marxist intellectuals

such as Benedetto Croce and Werner Sombart) argued, drawing

antagonistic approaches with long-lasting consequences within

Marxism and the workers movement.

Nothing of that sort came out of the “crisis of Marxism”

of the late 1970s and early 1980s. As can be seen from the

interventions of Rossanda and Althusser that set the terms of the

debate, at no moment was the shared diagnosis of the strategic

impasse in the West and the failure of Stalinism and its avatars in

the East situated within the wider perspective of the ongoing

transformation of capitalism on a world scale. The term “capitalism”

is indeed remarkably absent from those exchanges, anticipating its

eclipse from academic and public debate in the period that followed.

Indeed, what came quickly to prevail, at least in Latin Europe and

in the areas where Marxism was the most influential in the previous

period, is Althusser’s theoreticist approach, which located the

reasons of the crisis in the “gaps” and “enigmas” of the Marxian and

Marxist canon. Rossanda’s call for a historical-materialist analysis

of the conjunctures that led to the emergence of Stalinism and the

defeat of socialist revolution in the West remained unanswered.

Rather than the promised reflective and self-critical renewal, the

introverted character of the debate launched by the “crisis of

Marxism” internalized and amplified the historical defeat of which

it was both an anticipatory sign and a symptom.

It then comes as no surprise that the “new revisionism”

that emerged from that crisis, under the label of “Post-Marxism”,

amounted to a form of disintegration from within of the dominant

Western Marxist paradigm of the previous period, that is,

Althusserianism. In the radically transformed “post-modern”

atmosphere of the 1980s and after, the search for the ultimate unity

of a “structured totality” came to be seen as at best irrelevant,

and most commonly as an expression of a desire for “closure” that

can only pave the way to “totalitarianism”. The “overdetermination”

of conjunctures becomes pure “contingency”, the “materiality of

ideology” is turned into a discourse-based ontology of the “social”

guaranteeing its radical “indeterminacy”. As Fredric Jameson

underlined, this move should itself be seen as part of the broader

shift from what is called “structuralism” to “post-structuralism”, a

shift that marks the passage to a new period at the political, the

cultural and the economic levels. The central notions of the 1960s

theoretical revolution, from semiotics and structural anthropology

to anti-humanist Marxism, “fall-back into a now absolutely

fragmented and anarchic social reality (…), as so many more pieces

of material junk among all the other rusting and superannuated

apparatuses and buildings that litter the commodity landscape and

that strew the ‘collage city’, the ‘delirious New York’ of a

postmodernist late capitalism in full crisis” (Jameson 1984, 506).

Let us examine more

closely how these themes have played out in what should undoubtedly

be considered as the manifesto of this 1980s “Post-Marxism,” Ernesto

Laclau and Chantal Mouffe’s

Hegemony and Socialist Strategy

(Laclau and Mouffe 1985)[1].

Their starting point is quite similar to Bernstein’s

“revisionism”: the question of “revolutionary agency”, with its

“historical-sociological” and political-strategic implications.

Marxism’s unsurmountable flaw, according to Laclau and Mouffe, is to

consider as a given the existence of a unified social subject, the

working class, in charge of a historical mission, the revolutionary

overthrow of capitalism. This vision is grounded in a deterministic

vision of social relations, which sees the centrality of class

struggle (and the corresponding form of consciousness) as guaranteed

by the “determination in the last resort by the economy.” In a word,

Marxism is guilty of "essentialism" and, as a consequence,

increasingly unable to grasp the forms of subjectivation that

prevail in contemporary conjunctures. "Essentialism" is actually

nothing more than an attempt, as illusory on the analytical plane as

it is vain at a practical level, to fill the constitutive

indeterminacy of the social and the ensuing decentred character of

the forms of subjectivation. No wonder then that the working class

never fulfilled its alleged historical mission. Marxism is thus left

in disarray when confronted with the fragmented and open

configuration of the “new social movements” (such as feminism,

ecology, sexual and ethnic minorities), irreducible to any class

essentialism.

Even worse, Marxism should also be held responsible

both for the authoritarianism inherent in the Leninist type of

organization and for the totalitarian regimes that claimed its

legacy. A number of features, all intrinsic to Marxian and Marxist

theory, has inevitably led to this historical disaster. At first,

class essentialism cannot be dissociated from a purely instrumental

conception of democracy and of civil liberties. Marxists are

expected to fight for them as long as they are useful for them

seizing power, but, as such, their class nature is seen as

irretrievably “bourgeois”. Therefore, once in power, the proletariat

“would be the first to abolish them once the ‘bourgeois-democratic’

stage [of the revolution] was completed” (Laclau and Mouffe 1985,

55). Secondly, Marxism extends the “ontological primacy granted to

the working class” from the social to the political level. The

Leninist party, and, eventually, the state dominated by that party,

act as the sole legitimate leadership of the broader masses

regrouped under the hegemony of the revolutionary class. Hence a

“predominantly external and manipulative character” of the

leadership, displaying “an increasingly authoritarian practice of

politics” (Laclau and Mouffe 1985, 56). But this ontological primacy

of class was also extended to an epistemological privilege. The

party becomes the depository not only of political correctness but

also of science. Once Marxists are in power, their vision led

directly to totalitarianism, defined as the forced unification of

law, power and knowledge under the auspices of a “unitary people”

(Laclau and Mouffe 1985, 187). Laclau and Mouffe emphasize that the

“possibility of the authoritarian turn was, in some way, present

from the beginning of the Marxist orthodoxy; that is to say, from

the moment, in which a limited actor – the working class – was

raised to the status of a ‘universal class’ ” (Laclau and Mouffe

1985, 57). Marxism is doomed to disaster by its desire to “suture”

the social, that is, to reduce – if necessary through violence – its

constitutive openness under a single, unitary, meaning, provided by

the alleged truth of revolutionary class consciousness.

As opposed to Marxism, Post-Marxism as defined by Laclau

and Mouffe categorically rejects class determinism to emphasize the

constitutive role of discursive articulations and the indeterminacy

of the social. Discourse holds a sort of ontological primacy since

“our analysis rejects the distinction between discursive and

non-discursive practices” (Laclau and Mouffe 1985, 107) insofar as

nothing can be considered as external to discourse and/or

irreducible to discursive articulations – including the economy

(76-77). As a notion, “discourse” is thus equivalent to the

Heideggerian “Being” (filtered by Derrida’s ‘deconstruction’), whose

meaning remains always hidden, and therefore adequate to the

“impossibility of the real” (Laclau and Mouffe 1985, 129), the

impossibility of achieving the fullness of a “presence”, of a fixed

essence that would amount to its closure. It is only through the

practice of discursive articulation that the openness of the social

can give rise to forms of political subjectivation, but always and

solely in a contingent, partial and temporary mode. “Hegemony” is

the proper name of this practice: it consists in establishing chains

of equivalence between the heterogeneous demands emerging from the

social and transforms the very identity of the terms that come under

this articulatory relation. This approach thus makes intelligible

the irreducible plurality of political subjects that succeed the

defunct centrality of workers while contributing positively to their

emergence.

Liberal Democracy as the

Ultimate Horizon

Laclau’s and Mouffe’s theoretical ambition goes

however further than an epistemological claim. The task they

attribute to Post-Marxism is to turn the theory and practice of

hegemony decisively in the direction of democracy. The relation

between the two terms appears indeed as an ambivalent one, subjected

to a tension between a “democratic and an authoritarian practice of

hegemony” (Laclau and Mouffe 1985, 57). From the outset the

political space of modernity appears as divided between these two

modes of subjectivity. The modern political actor corresponds to a

“popular subject position”, constituted by the chain of equivalence

defining an “us” as opposed to “them”. Its logic is the two of an

antagonism. But antagonism is irreducibly plural, it cannot be

subsumed under any single, allegedly “objective”, contradiction. The

“democratic subject position” recognizes this impossibility and

opens up a common space, in which these antagonisms can only

coalesce in a partial and contingent way through their articulation

with other elements. Ecological, feminist, national or workers’

movements can therefore take many, sometimes diverging, forms

depending on the way they are discursively articulated. The logic of

the “democratic subject position” isn’t the two but the many, the

radical pluralism of identities: “pluralism is radical only to the

extent that each term of this plurality of identities finds within

itself the principle of its own validity” (Laclau and Mouffe 1985,

167).

We are here in the field of the

multiplicity of Wittgensteinian “language games” (Laclau and Mouffe

1985, 179) understood as a proliferation of discursive operations

across an increasingly complex social terrain made of fragmented and

autonomous spheres. This multiplicity should be preserved at all

costs since its negation would amount to that “suture of the

social”, which is the original sin of Marxism but, also, as we shall

now see, of right-wing authoritarianism.

This dual character of the political space leads

therefore to a fundamental consequence: the relation between the two

modes of political subjectivity is of complementarity but also of

tension. The creative character of politics requires the deployment

of the logic of equivalence. But the antagonism carried by that

logic can potentially constitute a threat to pluralism, and, as a

consequence to democracy as the common ground which allows the

differentiation (of “separation of spaces”) that is required by the

construction of equivalences to operate. Equivalence and plurality

need therefore to limit each other, and, most significantly, the

first should never pretend, or be allowed, to absorb the second.

This imperative can also be formulated as the necessity to “balance”

equivalence by autonomy, or “equality” by “liberty”. It doesn’t take

much effort to recognise here the terms in which liberalism has

always framed the question of democracy: the threat of an

egalitarian democracy that would undermine the “separation of

spaces” – in Marxist terms the (relative) separation of the

political and the economic as the distinctive dimension of

capitalism[2]

– should be removed, or at least contained, in order to preserve the

space of liberty. As stated by Laclau and Mouffe,

the

demand for

equality

is not sufficient, but needs to be balanced by the demand for

liberty, which leads up to

speak of a radical and

plural democracy. A radical

and non-plural democracy would be one which constituted

one single space of equality

on the basis of the unlimited operation of the logic of equivalence

and did not recognize the irreducible moment of plurality of spaces.

This principle of the separation of spaces us the basis of the

demand of liberty. It is within it that the principle of pluralism

resides and that the project for a plural democracy can link up with

the logic of liberalism (Laclau and Mouffe 1985, 184).

The spectre looming behind this threat is nothing

else than revolution, not only socialist revolutions but also the

French Revolution – at least in its Jacobin moment[3]

– held as equally responsible for the totalitarian path eventually

pursued by Stalinism. It is essential to understand, according to

the authors of

Hegemony and Socialist Strategy,

that the “logic of totalitarianism” is a “new possibility which

arises in the very terrain of democracy” (Laclau and Mouffe 1985,

186). Its impulse comes from the tendency of the logic of

equivalence to expand, and this happens when “it ceases to be

considered as one political space among others and comes to be seen

as the centre, which organizes and subordinates all other spaces”

(186). As history has shown, “every attempt to establish a

definitive suture and to deny the radically open character of the

social which the logic of democracy institutes leads to what

[Claude] Lefort designates as ‘totalitarianism’ ” (187). This is why

every temptation to seek “a nodal point around which the social

fabric can be reconstituted” should be categorically rejected (188).

But this is precisely what the “classic concept of revolution, cast

in the Jacobin mould” is about, since “it implied the foundational

character of the revolutionary act, the institution of a point of

concentration of power from which society could be ‘rationally’

reorganized. This is the perspective which is incompatible with the

plurality and the opening which a radical democracy requires”

(177-178). Such a perspective is equally shared by Marxism and

Jacobinism: “this change introduced by Marxism [class] into the

principle of social division maintains unaltered an essential

component of the Jacobin imaginary: the postulation of one

foundational moment of rupture, and of a unique space in which the

political is constituted” (152).

‘Totalitarianism’ exists

however also in a symmetrical right-wing version, that of fascism’s

“authoritarian fixing of the social order” (Laclau and Mouffe 1985,

188). Totalitarianism as such is therefore “a

political logic

and not a type of social organisation” and this is “proved by the

fact that it cannot be ascribed to a particular political

orientation” (187). This position is the logical consequence of the

radical decoupling of the political from any socio-economic

determination and its reduction to a discursive construction.

Fascism and communism differ to the extent that they represent

different “particular political orientations”, corresponding to

different “types of social organisation”, however this opposition is

of secondary importance (hence the use of the term ‘particular’ to

refer to their respective ‘political orientations’) compared to what

both share: a common desire “to establish a definitive suture and to

deny the open character of the social which the logic of democracy

institutes” (187). It is not difficult to trace in this

“anti-totalitarianism” a variant of the Cold-War discourse that

became dominant during the Thatcher-Reagan era. Far from being a new

(or even a 20th

century) construction this anti-totalitarianism is the heir a

liberal tradition descending in a straight line from Burke’s and

Tocqueville’s view of the French Revolution as a catastrophe

resulting from a desire to rebuild society from scratch, i.e.

according to “abstractions” and “preconceived systems” (Losurdo

2015).

The “radicality” of

“radical democracy”, as Laclau and Mouffe name their project, should

therefore not be confused with any notion of “revolution.” They make

it clear that by the term “radical alternative” they are “evidently

not referring to a ‘revolutionary alternative’, involving the

violent overthrow of the existing state, but to a deepening and

articulation of a variety of antagonisms, within both the State and

civil society, which allows a ‘war of position’ against the dominant

hegemonic forms” (Laclau and Mouffe 1985, 75). Rather than Gramsci,

the literal but actually superficial reference, the model for this

“war of position” is provided by Alexis de Tocqueville’s notion of

“democratic revolution” as a movement of expansion of rights into

new spheres within the limits imposed by the respect of “pluralism”

and of the “separation of spheres” (Laclau and Mouffe 1985,

160-163). This “revolution” was conceived by the French liberal

thinker as the movement of a gradual but continuous erosion of

traditional hierarchies, as a movement of permanent mobility and

circulation of individuals and wealth across the social ladder.

Likewise, for the theorists of Post-Marxism, it allows the

questioning of “relations of subordination” both by “old” and “new”

social movements and the extension of “rights” to new fields. The

“new social movements” (ecology, feminism, minorities) appear

however as the most appropriate vehicles for such a strategy, since

they are explicitly based on non-class principles and flexible modes

of identity and alliance formation. They appear therefore as the

driving social force within societies characterized by an increasing

autonomization of social activities. However, really existing

workers struggles (as opposed to the illusory messianic vision of

the proletariat) can and should also be understood in that way.

These struggles, dismissed as “reformist” by Marxists, “correspond

more in reality to the mode adopted by the mobilisations of the

industrial proletariat than do the more radical earlier struggles”

(157). Their modernity lies in the fact that, contrary to the

radically hostile to capitalism visions of the semi-artisans still

caught in the preindustrial imaginary depicted by E. P. Thompson in

The Making of the English Working Class,

“the relations of subordination between workers and capitalists are

thus to a certain extent absorbed as legitimate differential

positions in a unified discursive space” (157).

This last formulation is

particularly revealing of the way “radical democracy” is ultimately

understood as a struggle between “logics” contesting existing forms

of inequality and subordination but always within an unchanged

overall framework. This unnamed totality turns out being nothing

else than capitalism, the system in which the “legitimate

differential positions” of workers and capitalist can as it were

persist in their being. Indeed, only capitalism allows the “openness

of the social” based on the “separation of spheres which constitutes

the indispensable condition for political pluralism, or, in other

terms, for the “institutional diversity and complexity which

characterizes a democratic society” (Laclau and Mouffe 1985,

190-191). It is therefore perfectly consistent with their line of

thought to define “the task of the Left” as a move “to deepen and

expand [liberal-democratic ideology] in the direction of a radical

and plural democracy” (176). The claim made twice, and almost in

passing, about the necessity to “put an end to the capitalist

relations of production”, as “one

of the components of a project for radical democracy” (178) and

without this entailing the “elimination of other inequalities” as

its consequence (192), appears thus as little more than a rhetorical

gesture aimed at giving a residual left-wing flavour to an

enterprise of systematic demolition of the very idea of

anticapitalism as the basis for any consistent emancipatory project.

The Revenge of Totalization

Laclau’s and Mouffe’s 1985 book and the work that

followed on “agonism” and “populist reason” had a long-lasting

impact not only in the intellectual debate but also in the new

political sequence opened-up by the 2008 crisis, as testified by the

rise of “left-populist” movements in Europe such as Podemos and

France Insoumise. Many of its themes are shared other theorists who,

notwithstanding divergent theoretical frameworks and political

conclusions, found themselves in agreement with what it breaks from

– class politics, the critique of political economy – as well as

with some of the positive elements that take centre stage: a version

of the “linguistic turn” and the rehabilitation of the categories of

political liberalism. Habermas’s theory of “communicative action”,

Honneth’s “politics of recognition”, Foucault’s notions of “power”

and “discursive formations” (but also his late fascination with

ordoliberalism) are obvious cases of

such

an evolution. In their work from the 1980s onwards, even figures who

kept closer ties with Marxism and anticapitalism such as Toni Negri

followed a partly convergent trajectory, elaborating on themes such

as “immaterial labour”, the “multitude” as the new subject of

politics and the expansion at the world-scale of the US constitution

as the horizon of social movements in the new reality of an

allegedly post-imperialist and post-national “Empire”.

“Post-Marxism” became thus the name of a broader constellation that

expressed a substantial part of the “objective Spirit”, to quote

Hegel’s term, of the historical moment marked by the defeat of the

revolutions of the 20th

century.

Not that everyone agreed with this turn of events.

The Post-Marxism advocated by Laclau and Mouffe was, as could be

expected, met by strong rebuttals coming from Marxist theorists,

with Ellen Meiksins Wood and Norman Geras making the most

significant contributions (Wood 1986, Geras 1990). What came

essentially under criticism was their distorted understanding of

Marxist concepts and their thinly disguised belief in the virtues of

liberal democracy. The paradox here is that, despite the intensity

of the polemics, Marxists and Post-Marxists shared the same terrain,

that of a conceptual discussion moving in the terrain of

intellectual history and Marxist theory, with some sparse references

to the political conjuncture of the moment in order to denounce the

toothless politics attributed to Post-Marxists. Thus, although most

of the Marxist reaction to Post-Marxism was driven by a strong

rejection of Althusser[4],

it adopted

de facto

the “theoreticist” approach of the “crisis of Marxism” expressed by

the French philosopher. These polemics have little, if anything, to

offer concerning the transformations capitalism, the state and the

social structure were undergoing in the 1980s. At a moment of deep

retreat of the left and of social movements, critical thinking and

emancipatory politics came out even weaker from the late 20th

century “crisis of Marxism”.

A new picture only started emerging when the

contradiction created by the fall of “really existing socialism” and

the now unchallenged domination of neoliberal capitalism at a global

scale began to unfold. Various trends, each with a distinctive

temporality, converged, shifting gradually the terms of the debate.

The first of these is the dissent that developed from

within the Post-Marxist constellation. Its most significant

expression was Slavoj Žižek’s turn towards a critique of the

theoretical matrix from which his previous work had developed (Žižek

1999, Butler, Laclau and Žižek 2000). Although Žižek’s entire

trajectory is grounded on the writings of Althusser and Lacan, his

fondness for Hegel and for dialectical thinking always made him

always appear as a highly atypical post-structuralist. From the late

1990s onwards, he moved to an internal but systematic contestation

of the positions of Laclau and Mouffe, enlarged to those of other

figures such as Judith Butler or Jacques Rancière. Starting from a

notion assimilating subjectivity to the Hegelian labour of

negativity, Žižek now affirms the necessity of a global alternative

to capitalism. He thus rejects the compulsive Post-Marxist

insistence on the radical “openness” and “indeterminacy” of the

social, emphasizing that capitalism acts as the force closing

violently the possibilities of the Real by imposing the centrality

of class antagonism. He thus comes to share Fredric Jameson’s

longstanding view that totalisation isn’t a matter of choice but

something imposed by the existing, albeit unrepresentable, totality

that is capitalism.

The closure inherent in the prevailing social order

can only be broken by the foundational act of a revolutionary

subject, who bets on the constitutive void of a given situation, a

vision reminding us of Sartre’s notion of freedom as an act bringing

nothingness to the world, mediated by Alain Badiou’s theory of the

Event. Leninist politics is thus rehabilitated, much to the chagrin

of Laclau, not as offering the right theory of the party but as the

model of an act of radical rupture opening up the possibility of a

new order, of which the moment of the October revolution still

provides the standards (Žižek 2004).

Notwithstanding

significant problems of internal consistency (see Callinicos 2001),

and a persistent lack of strategic thinking – in line with the

“poverty of strategy” of Western Marxist thought – Žižek’s evolution

can be seen as a attempt to articulate decisionism to the

reinstatement of the dialectical categories of necessity and

contingency (the Hegelian movement of the concept posing its own

presuppositions), as a necessary tool for the understanding of

historical processes – another strong rebuttal of the

Post-Marxist/post-modern cult of “contingency”.

This break from within

Post-Marxism reveals the internal instability of this constellation,

deriving from the reactive character inscribed in its very name. The

ambition to supersede Marxism while inheriting its ambition of a

theory linked to a form of emancipatory project – even if the

totalizing dimension and the notion of ‘emancipation’ itself came

under heavy criticism – proved more fragile than what was widely

accepted in the first decades that followed the end of the “short 20th

century”. However, this crack wouldn’t have sufficed to change the

terms of the debate had Marxist theory not proved remarkably

resilient throughout the period when (nearly) all sides proclaimed

its death had arrived. A number of thinkers of the generation of the

1960s and the 1970s, mostly based in the world of Anglophone

academia, persisted in providing ambitious totalizing analyses of

the fundamental aspects of the transformations of the existing mode

of production.

To name just a few, let’s start with Fredric Jameson and

his notion of “post-modernism” as the “cultural logic of late

capitalism”. Faithful to the categorical imperative of Marxism

“Always historicize!” (Jameson 1981, 9), intensified by an “unslaked

thirst for totalization” (Kouvelakis 2008b), Jameson offered a vast

typology of this pervasive restructuring of social experience

characterized by a dehistoricized and dislocated (or “depthless”)

sense of space and time. As an immanent expression of a distinctive

stage of capitalism, the all-pervasive postmodern logic – rather

than specific currents identifiable as “postmodernist” – acts as a

powerful counterweight to the emergence of class consciousness (or

“cognitive mapping” in Jameson’s terms).

Inspired by the work of Henri Lefebvre and other thinkers

of the historical-materialist tradition (such as Engels and Rosa

Luxemburg), David Harvey has developed the (so far) most systematic

Marxist theory of space as the terrain in which the mode of

production displaces and temporarily resolves its own structural

contradictions – through a process of constant production of

“spatio-temporal fixes.” Harvey extended his theory to a

periodization of capitalism, exploring the specificities of the

current moment in his analysis of neoliberalism and the “new

imperialism.” At a more empirical level, Mike Davis provided

extraordinary vivid accounts of the formation of these new forms of

high-capitalist hyper-spaces, from California’s dystopic “city of

quartz” and the urban artefacts of Dubai to the “gated communities”

booming around the globe or sprawling of slums in the cities of the

global South. Davis’s preoccupations resonate with a rising body of

work from theorists such as Paul Burkett, John Bellamy Foster,

Michael Löwy and Andreas Malm on capitalism’s role in the ongoing

environmental catastrophe, the ecological dimension of Marxian

thought and the eco-socialist alternative.

This strongly “spatial”

Marxism explains the strong presence of a critically oriented

research in most university departments of geography and urban

studies and acts as an inspiration for activists involved in

innumerable struggles contesting capital’s spatial order. It is

supplemented by the renewal of Marxist political economy retraced by

Alex Callinicos in his chapter, “Hidden Abode”, in this volume. The

realities of financialized capitalism were the object of systematic

scrutiny by economists such as François Chesnais, Gérard Duménil,

Cédric Durand, Costas Lapavitsas and Anwar Shaikh even before the

2008 Great Recession, which, as noted previously, triggered a

broader attention to the Marxist understanding of contemporary

capitalism and its crises. A widely similar picture emerges from the

fields of international relations, labour studies and of the theory

of the neoliberal state and the world legal order. Even if a strong

philosophical current continued to produce an important and

innovative body of work (mostly in Italy and France, around figures

such as Domenico Losurdo, André Tosel and Daniel Bensaïd), it cannot

be said anymore that the type of Marxist theorizing that flourishes

in the Western world shares the essential characteristics once

attributed by Anderson to “Western Marxism” (Anderson 1976).

Although clearly a heir of the 20th

century heterodoxies associated with that tradition, it has

decisively stopped concentrating on its essentially aesthetical and

speculative themes to pick up the thread of research on political

economy and social and political theory.

This renewal of Marxism signals a new intellectual

conjuncture and testifies to its capacity to withstand the

challenges posed by its protean Other, capitalism, and by the

failures of the experiments conducted in its name. It comes however

at a cost, that of retreating into an essentially academic sphere,

accentuating the problematic relation to political practice that

characterized the previous configuration. In that sense, the “crisis

of Marxism,” as a diagnosis on the crisis of the perspectives of the

socialist and communist project, is still with us and will remain as

long as a new victorious experience of emancipatory struggle hasn’t

come into being. But one should also keep in mind that what

initially appears as a purely intellectual phenomenon often turns

out to be the anticipatory sign of a deeper historical trend. The

future of Marxism as an active force aiming at changing the world

could thus still surprise.

Bibliography

Althusser, Louis. 2006 [1978]. “Letter to Merab Mamardachvili”. In

Louis Althusser,

Philosophy of the Encounter. Later

Writings 1978-1987. London &

New York: Verso.

Althusser, Louis, 1971 [1968]. “Philosophy as a Revolutionary

Weapon”. In Louis Althusser,

Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays.

London: New Left Books.

Althusser, Louis, 1976 [1973]. “Reply to John Lewis”. In Louis

Althusser,

Essays in Self-Criticism.

London: New Left Books.

Althusser, Louis. 1977. “The Crisis of

Marxism”. Available at

viewpointmag.com/2017/12/15/crisis-marxism-1977/ last

accessed April 7 2018.

Anderson, Perry. 1976.

Consideration on Western Marxism.

London: New Left Books.

Anderson, Perry. 1983.

In the Tracks of Historical Materialism.

London: New Left Books.

Artus, Patrick.

2018. “La

dynamique du capitalisme est aujourd’hui bien celle qu’avait prévue

Karl Marx”,

Natixis Flash Economie:

February 2 2018.

Available at

research.natixis.com last accessed April 7 2018.

Bensaïd, Daniel.

2007.

Eloge de la politique profane.

Paris: Albin Michel.

Bidet, Jacques, and

Stathis Kouvelakis eds. 2008.

Critical Companion to Contemporary Marxism.

Chicago: Haymarket.

Butler, Judith, Ernesto Laclau, and

Slavoj Žižek,. 2000.

Contingency, Hegemony, Universality. Contemporary Dialogues on the

Left. London & New York:

Verso.

Callinicos,

Alex

. 2001.

“Review of Slavoj Žižek,

The Ticklish Subject,

and Judith Butler, Ernesto Laclau and Slavoj Žižek,

Contingency, Hegemony, Universality.”

Historical Materialism 8:

373-403.

Chotiner, Isaac. 2014. “Thomas Piketty: I don’t care for Marx.”

The New Republic:

May 6 2014.

The Economist. 2014.

“A Modern Marx. Capitalism and its Critics”.

economist.com/news/leaders/21601512-thomas-pikettys-blockbuster-book-great-piece-scholarship-poor-guide-policy

last accessed April 4 2018.

Drury, Colin. 2018. “Mark Carney warns

robots taking jobs could lead to rise of Marxism.”

Independent: April 14 2018.

independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/mark-carney-marxism-automation-bank-of-england-governor-job-losses-capitalism-a8304706.html last accessed June 11 2018.

Duménil,

Gérard and Dominique Lévy.

2014. “Économie et politique des thèses de Thomas Piketty. I.

Analyse critique.”

Actuel Marx

56: 164-179.

Duménil,

Gérard, and Dominique Lévy.

2015. « Économie et politique des thèses de Thomas Piketty: II. Une

lecture alternative de l’histoire du capitalisme. »

Actuel Marx

57: 186-204.

Elliott, Gregory.

1986. “The Odyssey of Paul Hirst.”

New Left Review I/159:

81-105.

Lordon, Frédéric.

2015. « Why Piketty isn’t Marx. »

Le Monde diplomatique.

May 2015.

Geras, Norman. 1990.

Discourses of Extremity. Radical Ethics

and Post-Marxist Extravagances.

London and New York: Verso.

Haider, Asad and Patrick King, eds. 2017. “The Crisis of

Marxism” [texts by Louis Althusser, Etienne Balibar, Christine

Buci-Glucksmann, Nicos Poulantzas, Rossana Rossanda].

viewpointmag.com/2017/12/18/the-crisis-of-marxism last accessed April 10 2018.

Jameson, Fredric. 1981.

The Political Unconscious: Narrative as Socially Symbolic Act.

London: Methuen.

Fredric Jameson. 2009

(1984). “Periodizing the 60s”. In Fredric Jameson,

The Ideologies of Theory,

483-515. London and New

York: Verso.

Kouvelakis, Stathis. 2008a. “The Crisis of Marxism and

the Transformation of Capitalism.” In Bidet and Kouvelakis 2008,

23-38.

Kouvelakis, Stathis. 2008b. “Fredric Jameson: An

Unslaked Thirst for Totalisation.”

In

Bidet and Kouvelakis 2008, 697-710.

Laclau, Ernesto and

Mouffe, Chantal. 1985.

Hegemony and Socialist Strategy.

London and New York: Verso.

Losurdo, Domenico. 2015.

War and Revolution. Rethinking the 20th

Century. London and New

York: Verso.

Lyotard, Jean-François.

1984 (1979).

The Postmodern Condition: A Report on

Knowledge. Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press.

Nienhaus, Lise. 2017.

“Karl Marx: Er ist wieder da”.

Die Zeit 5/2017

zeit.de/2017/05/karl-marx-kapitalismus-probleme-rechtspopulismus-ungleichheit last accessed April 4 2018.

Piketty, Thomas. 2014.

Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Rossanda, Rossana. 1977. “Power and Opposition in

Post-Revolutionary Societies”.

viewpointmag.com/2017/12/15/power-opposition-post-revolutionary-societies-1977/ last accessed April 10 2018.

Roubini, Nouriel. 2011. “Roubini

warns of global recession risk”.

Wall Street Journal August

11 2011

wsj.com/video/roubini-warns-of-global-recession-risk/C036B113-6D5F-4524-A5AF-DF2F3E2F8735.html last accessed April 4 2018.

Streeck, Wolfgang. 2016.

How Will Capitalism End? Essays on a

Failing System. London & New

York: Verso.

Wood, Ellen Meiksins.

1981. “The Separation of the Economic and the Political in

Capitalism,”

New Left Review

I/127: 66-95.

Wood, Ellen Meiksins.

1986.

The Retreat from Class. A New “True”

Socialism. London and New

York: Verso.

Žižek, Slavoj.1999.

The Ticklish Subject. The Absent Centre of

Political Ontology. London &

New York: Verso

Žižek, Slavoj. 2004.

Revolution at the Gates: Zizek on Lenin: The 1917 Writings.

London & New York: Verso.

[1]

Although attributed to a large number of thinkers – the

Wikipedia article on the notion lists no less than 35 names,

even very unlikely ones (Abdullah Öcalan, Pierre Bourdieu or

Paulo Freire) - most of those who claimed the label of

“Post-Marxism” came from the Althusserian tradition: Etienne

Balibar, Barry Hindess, Paul Hirst, Gareth Stedman-Jones to

name a few. Most of the themes of post-Marxism, and of the

broader ‘post-structuralist’ constellation can be identified

in currents coming from other Marxist backgrounds, the such

as Italian post-operaismo, Indian “subaltern studies”,

versions of post-colonialism etc. The shared prefix “post”

is an unfallible sign of their common belonging to the

constellation of “post-structuralism”, or, better even, of

the “postmodern condition” to quote Jean-François Lyotard’s original

formulation (Lyotard 1984).

[2]

See Wood, 1981.

[3]

Laclau and Mouffe only praise the French Revolution,

following Hannah Arendt, François Furet and Claude Lefort to

whom they refer themselves, for its “1789 moment”, that is

for inaugurating a “new mode of institution of the social”,

symbolized by the Declaration of the Rights of Man seen as

providing the discursive basis for the “struggles for

political liberty” (Laclau and Mouffe 1985, 155). This is typically the traditional

liberal view of the Revolution, always carefully separating

the “good” 1789 moment from the “bad” 1793 one, the former

representing the conquest of liberty and the latter standing

for the drift toward ‘tyranny’ and ‘totalitarianism’.

[4]

For a different perspective see however

Elliott 1986.

Chủ nghĩa tân Marx

Vào thế kỷ 20 và 21, một số nhà xã hội học đã tiếp cận xã hội

với phương thức phân tích chịu ảnh hưởng rất nhiều từ các tác phẩm

của Karl Marx, tuy nhiên họ đã tiếp tục điều chỉnh chủ nghĩa Marx

truyền thống theo nhiều cách khác nhau. Ví dụ, một số người theo chủ

nghĩa Marx mới chia sẻ cách phân tích của Marx về chủ nghĩa tư bản

nhưng không chia sẻ niềm tin của ông vào một cuộc cách mạng cộng sản.

Những người khác (như Antonio Gramsci hoặc gần đây là Stuart Hall)

nhấn mạnh vào các khía cạnh văn hóa của xung đột giai cấp hơn là

trọng tâm kinh tế của các tác phẩm gốc của Marx. Những người đã điều

chỉnh các ý tưởng của Marx theo những cách này được gọi là những

người theo chủ nghĩa Marx mới.

Cách tiếp cận tân Marxist của Bắc Mỹ và cách tiếp cận lý

thuyết phụ thuộc của Mỹ Latinh có một số điểm chung, nhưng cũng có

một số khác biệt quan trọng.

Cách tiếp cận tân Marxist của Bắc Mỹ:

- Được phát triển bởi các học giả như Paul Baran và Paul

Sweezy vào những năm 1960.

- Tập trung vào vai trò của các tập đoàn đa quốc gia (MNC)

trong việc duy trì tình trạng kém phát triển ở Nam Bán cầu.

- Cho rằng các công ty đa quốc gia trích xuất giá trị thặng dư

từ các nước Nam bán cầu, khiến các nước này luôn phụ thuộc vào các

nước phát triển.

- Nhấn mạnh tầm quan trọng của các yếu tố nội tại như chính

sách nhà nước và quan hệ giai cấp, bên cạnh các yếu tố bên ngoài như

các công ty đa quốc gia.

- Xem Bắc và Nam bán cầu có mối liên hệ với nhau, và sự phát

triển của Nam bán cầu phụ thuộc vào những thay đổi cơ bản trong cấu

trúc nền kinh tế toàn cầu.

Cách tiếp cận của Mỹ Latinh:

- Được phát triển bởi các học giả như Raúl Prebisch vào những

năm 1950.

- Tập trung vào mối quan hệ giữa Bắc và Nam bán cầu, nhấn mạnh

vào thương mại quốc tế.

- Cho rằng sự trao đổi hàng hóa không bình đẳng giữa Bắc và

Nam bán cầu làm cho tình trạng kém phát triển ở Nam bán cầu kéo dài.

- Xem Bắc và Nam bán cầu về cơ bản là khác nhau và cho rằng sự

phát triển ở Nam bán cầu bị cản trở bởi các yếu tố bên ngoài như

quan hệ quyền lực trong lịch sử và chính sách kinh tế toàn cầu.

- Nhấn mạnh công nghiệp hóa thay thế nhập khẩu (ISI) và sự can

thiệp của nhà nước vào nền kinh tế như một phương tiện thoát khỏi sự

phụ thuộc vào các nước Bắc bán cầu.

Vì vậy, trong khi cả hai cách tiếp cận đều tập trung vào mối

quan hệ giữa Bắc và Nam toàn cầu và sự duy trì tình trạng kém phát

triển, chúng khác nhau ở chỗ nhấn mạnh vào các yếu tố bên trong so

với bên ngoài và vai trò của các công ty đa quốc gia. Cách tiếp cận

tân Marxist của Bắc Mỹ được coi là chỉ trích chủ nghĩa tư bản nhiều

hơn và nhấn mạnh vào nhu cầu thay đổi cơ bản đối với cấu trúc của

nền kinh tế toàn cầu, trong khi cách tiếp cận của Mỹ Latinh được coi

là tập trung nhiều hơn vào các can thiệp chính sách cụ thể để thúc

đẩy phát triển ở Nam toàn cầu.

Quan điểm của chủ nghĩa tân Marx về tôn giáo và thay đổi xã

hội

Không phải tất cả những người theo chủ nghĩa Marx đều coi tôn

giáo chỉ là một lực lượng bảo thủ. Người đồng nghiệp thân cận của

Marx là Friedrich Engels cho rằng tôn giáo có tính chất kép và có

thể hoạt động như một lực lượng bảo thủ nhưng cũng có thể thách thức

hiện trạng và khuyến khích thay đổi xã hội. Một số nhà văn theo chủ

nghĩa Marx và tân Marx đã phát triển ý tưởng này xa hơn nữa.

Tính cách kép và Ấn Độ giáo

Ý tưởng về một bản chất kép được minh họa rõ nét trong Ấn Độ

giáo , trong nhiều thế hệ, được sử dụng như một lực lượng bảo thủ

mạnh mẽ, không chỉ trong việc duy trì hệ thống đẳng cấp , nơi xã hội

Ấn Độ được chia thành các tầng lớp xã hội bất động ngay từ khi sinh

ra, với những người Dalits hay "những người không được đụng chạm" ở

dưới cùng của xã hội, bên ngoài chính hệ thống đẳng cấp. Tuy nhiên,

cùng một tôn giáo đã truyền cảm hứng cho sự thay đổi xã hội to lớn

trong phong trào dân tộc chủ nghĩa Ấn Độ, và đặc biệt là các nguyên

tắc bất bạo động và tự từ bỏ bản thân là trọng tâm của chiến dịch

cuối cùng thành công của Mahatma Gandhi chống lại Đế quốc Anh. Ngày

nay, Ấn Độ giáo một lần nữa được cho là thúc đẩy sự thay đổi xã hội,

như một yếu tố chính trong sự phát triển kinh tế của Ấn Độ, theo

Nanda .

Bloch - Nguyên lý của hy vọng

Ernst Bloch (1954) đã viết về Nguyên lý hy vọng. Ông lập luận

rằng các tôn giáo đã mang đến cho mọi người ý tưởng về một xã hội

tốt đẹp hơn; một cái nhìn thoáng qua về Utopia. Trong khi Bloch, với

tư cách là một người vô thần, nghĩ rằng đức tin tôn giáo là không

đúng chỗ, ông đã nhìn thấy trong đó một hy vọng về một xã hội tốt

đẹp hơn và một niềm tin rằng mọi người nên có thể có phẩm giá và

sống một cuộc sống tốt đẹp trong một xã hội tốt đẹp. Với nguy cơ đơn

giản hóa quá mức tác phẩm của Bloch, nó bao gồm ý tưởng rằng hy vọng

về một thế giới tốt đẹp hơn vốn có trong đức tin tôn giáo có thể ảnh

hưởng đến mong muốn về những điều tốt đẹp hơn trên Trái đất - để xây

dựng một thiên đường trên Trái đất, hoặc một Jerusalem mới - và có

thể giúp tập hợp mọi người để tổ chức nhằm mang lại sự thay đổi xã

hội mang tính cách mạng.

Peter Beyer (1994) đã

xác định ba tác động chính của toàn cầu hóa đối với tôn giáo:

Chủ nghĩa đặc thù

– tôn giáo ngày càng được sử dụng như một con đường cho hoạt động

chống toàn cầu hóa. Trong khi một đặc điểm của toàn cầu hóa là một

dạng đồng nhất hóa văn hóa (tạo ra một nền văn hóa đại chúng toàn

cầu duy nhất) thì tôn giáo thường được coi là đối lập với điều đó:

một biểu tượng về cách mọi người khác biệt về mặt văn hóa với nhau,

chứ không phải giống nhau. Điều này đã góp phần vào sự gia tăng của

chủ nghĩa chính thống và là một đặc điểm của xung đột chính trị ở

nhiều khu vực trên thế giới.

Chủ nghĩa phổ quát – tuy nhiên cũng có một số bằng chứng về xu hướng ngược lại.

Trong khi các nhóm theo chủ nghĩa chính thống nhỏ có thể nhấn mạnh

sự khác biệt của họ với những người khác, các tôn giáo lớn ngày càng

tập trung vào những gì đoàn kết họ. Khác xa với sự xung đột đáng sợ

của các nền văn minh (sẽ được đề cập sau), các nhà lãnh đạo tôn giáo

nhấn mạnh các giá trị chung và mối quan tâm chung. Thật vậy, đối

thoại liên tôn thông qua giao tiếp toàn cầu đã giúp xoa dịu xung đột

giữa các tôn giáo.

Sự thiểu số hóa – Beyer cũng lưu ý rằng tôn giáo ngày càng bị thiểu số hóa

trong xã hội đương đại, ít đóng vai trò hơn trong đời sống công cộng,

mặc dù đây có thể là quan điểm mang tính Âu châu và có thể là do

những thay đổi xã hội khác chứ không phải do toàn cầu hóa.

Một cách khác mà toàn cầu hóa tác động đến tôn giáo là cách

các tôn giáo sử dụng truyền thông toàn cầu . Các nhóm tôn giáo có

thể tận dụng công nghệ hiện đại để tuyển dụng thành viên mới, truyền

bá thông điệp và giữ liên lạc với các thành viên khác của tôn giáo.

Trong khi với một số tổ chức tôn giáo cực đoan, phản hiện đại, phản

toàn cầu thì điều này có thể có phần trớ trêu, nhưng đây là một

trong những cách mà tôn giáo ít liên quan đến quốc tịch hơn trước

đây.

Bản sắc tôn giáo ít gắn liền với bản sắc dân tộc hơn trước

đây. Hầu hết các tôn giáo chính trên thế giới đều mang tính quốc tế

và trong khi một số quốc gia vẫn có tôn giáo nhà nước rõ ràng, thì

chắc chắn nó không còn là đặc điểm của bản sắc dân tộc ở phương Tây

như trước đây nữa. Tuy nhiên, đôi khi mọi người vẫn gọi các quốc gia

như Vương quốc Anh là "các quốc gia theo đạo Thiên chúa".

Một ngoại lệ đáng kể là Ấn Độ. Meera Nanda (2008) lập luận

rằng Ấn Độ giáo có liên quan chặt chẽ đến chủ nghĩa dân tộc Ấn Độ.

Trong một cuộc khảo sát, 93% người Ấn Độ coi nền văn hóa của họ là

“vượt trội hơn những nền văn hóa khác” và bản sắc dân tộc Ấn Độ và

Ấn Độ giáo ngày càng được coi là giống nhau. Nói cách khác, Ấn Độ

giáo đã trở thành thứ mà Bellah gọi là tôn giáo dân sự. Thông qua

việc thờ phụng các vị thần Hindu, người Ấn Độ đang tôn thờ chính Ấn

Độ.

Đã có "Tôn giáo Thế giới" từ rất lâu trước khi quá trình toàn

cầu hóa được cho là bắt đầu. Đặc biệt là Cơ đốc giáo, Hồi giáo và Do

Thái giáo đã có mặt trên nhiều quốc gia và châu lục. Tuy nhiên, một

số nhà xã hội học cho rằng toàn cầu hóa đã dẫn đến sự lan rộng nhanh

chóng của một số tổ chức tôn giáo. David Martin (2002) chỉ ra sự

phát triển của Ngũ tuần giáo (một giáo phái Cơ đốc) trên khắp thế

giới đang phát triển. Martin đối chiếu Ngũ tuần giáo với Công giáo.

Martin lập luận rằng nhiều đặc điểm của Ngũ tuần giáo khiến người

dân ở những vùng nghèo hơn trên thế giới yêu mến trong thời đại toàn

cầu hóa. Đầu tiên, mọi người chọn gia nhập nhà thờ thay vì sinh ra

trong đó. Thứ hai, nó được coi (đúng hay sai) là đứng về phía người

nghèo, thay vì là một tổ chức cực kỳ giàu có. Thứ ba, nó không liên

quan đến nhà nước hoặc chính phủ trong khi nhà thờ Công giáo thường

có mối liên hệ chặt chẽ với nhà nước. Cuối cùng, nó ít phân cấp hơn

nhà thờ Công giáo. Như vậy, ở những khu vực mà nhà thờ Công giáo

từng thống trị nhưng hiện đang trì trệ và mất đi sự ủng hộ, thì Ngũ

Tuần lại đang phát triển mạnh mẽ.

Trong khi Martin trình bày một cách mà các tổ chức tôn giáo tự

phản ứng với toàn cầu hóa, Giddens (1991) trình bày một cách khác

đang ngày càng rõ ràng hơn trong xã hội đương đại: chủ nghĩa chính

thống.

Chủ nghĩa chính thống

Chủ nghĩa chính thống thường được định nghĩa là chủ nghĩa hiếu

chiến tôn giáo mà các cá nhân sử dụng để ngăn chặn bản sắc tôn giáo

của họ bị xói mòn. Những người theo chủ nghĩa chính thống lập luận

rằng các tín ngưỡng và hệ tư tưởng tôn giáo ngày càng bị làm loãng

và bị đe dọa. Do đó, họ ủng hộ rằng các cá nhân nên sử dụng các văn

bản tôn giáo và tuân theo truyền thống để ngăn chặn bất kỳ sự xói

mòn nào nữa đối với bản sắc tôn giáo của họ do sự thế tục hóa gây ra.

Ví dụ; ISIS lập luận rằng Hồi giáo chính thống đã bắt đầu phớt lờ

một số giáo lý cơ bản từ Kinh Qur'an và Tiên tri Muhammad, do đó, họ

lập luận rằng những giáo lý này phải được tuân theo như mô tả trong

Kinh Qur'an để ngăn chặn bản sắc tôn giáo bị làm loãng hoặc mất đi.

Gramsci

Antonio Gramsci là một người theo chủ nghĩa Marx người Ý,

người đã viết rất dài về cách mà giai cấp tư sản duy trì quyền lực

trong các xã hội tư bản, phần lớn được viết trong tù khi bị chế độ

phát xít của Mussolini giam giữ. Ông đưa ra một cách hiểu tinh vi

hơn về cách thức duy trì một hệ tư tưởng thống trị so với cách mà

Althusser đưa ra. Ông lập luận rằng thông qua văn hóa, giai cấp tư

sản có thể duy trì quyền bá chủ: một tập hợp các ý tưởng thống trị

được coi là lẽ thường.

Gramsci đồng ý với Marx, Lenin và Althusser rằng tôn giáo đóng

một vai trò trong đó và góp phần vào sự kiểm soát bá quyền của giai

cấp thống trị. Tuy nhiên, giống như Engels, Gramsci không nghĩ rằng

đây là vai trò duy nhất mà tôn giáo có thể đóng. Công nhân có thể tổ

chức chống lại bá quyền và phát triển một phản bá quyền. Cũng giống

như tôn giáo có thể hữu ích cho việc xây dựng bá quyền tư sản, nó

cũng có thể hữu ích cho việc xây dựng một phản bá quyền, do các trí

thức hữu cơ lãnh đạo. Đối với Gramsci, các nhà lãnh đạo tôn giáo có

thể đóng vai trò là các trí thức hữu cơ, xây dựng một phản bá quyền,

phổ biến các ý tưởng trái ngược với ý tưởng của giai cấp thống trị

và giúp xây dựng sự nổi loạn và phản kháng.

Hai ví dụ về các nhà lãnh đạo tôn giáo hành động giống như các

nhà trí thức hữu cơ của Gramsci và sử dụng các ý tưởng trong tôn

giáo để vận động cho sự thay đổi đáng kể là:

Vai trò của Martin Luther King trong phong trào Dân quyền Hoa

Kỳ

Thần học giải phóng ở Mỹ Latinh.

Sau chiến tranh thế giới thứ hai, tại Hoa Kỳ, một phong trào

đã phát triển để chấm dứt chính sách phân biệt chủng tộc và phân

biệt chủng tộc tại Hoa Kỳ, và đặc biệt là chấm dứt luật Jim Crow ở

các tiểu bang phía Nam. Đây là những quy tắc phân biệt người da đen

và người da trắng ở nhiều nơi công cộng bao gồm cả trường học và ở

nhiều tiểu bang đã ngăn cản nhiều người da đen bỏ phiếu (và do đó,

không được tham gia bồi thẩm đoàn, v.v.). Những vụ ngược đãi khủng

khiếp đối với người da đen, bao gồm cả việc treo cổ của Klu Klux

Klan, diễn ra quá phổ biến. Các chiến dịch đòi quyền bình đẳng đã

diễn ra ở nhiều cấp độ và sử dụng nhiều chiến thuật khác nhau, nhưng

nổi bật nhất là các chiến dịch bất tuân dân sự của Mục sư Martin

Luther King, một giáo sĩ Cơ đốc giáo da đen đóng vai trò lãnh đạo

trong các chiến dịch. King đã kết hợp các giáo lý của Cơ đốc giáo

với các ý tưởng vận động của Mahatma Gandhi để thay đổi trái tim và

khối óc và cuối cùng là luật pháp ở Hoa Kỳ. Mặc dù King là một giáo

sĩ, nhưng đây không phải là một chiến dịch tôn giáo. Những nhà vận

động dân quyền khác có quan điểm tôn giáo khác (ví dụ, một số nhà

vận động hiếu chiến hơn đã gia nhập Quốc gia Hồi giáo, một giáo phái

Hồi giáo theo chủ nghĩa dân tộc da đen, ví dụ như Malcolm X.) Tuy

nhiên, tôn giáo đã đóng vai trò của mình theo những cách sau:

Nhà thờ cung cấp nơi ẩn náu cho những người vận động và trở thành

trung tâm vận động địa phương.

Việc sử dụng những câu Kinh thánh ủng hộ đã khiến giáo sĩ da trắng

và giáo dân xấu hổ khi ủng hộ phong trào này. Thật khó để bỏ qua

hoặc tranh luận với những mệnh lệnh rõ ràng như "yêu người lân cận".

Tương tự như vậy, những tuyên bố ăn sâu vào tâm lý người Mỹ, chẳng

hạn như "tất cả mọi người sinh ra đều bình đẳng trước Chúa" đã có

một ý nghĩa mới trong bối cảnh của chiến dịch.

Giáo hội Công giáo ở một số nước Mỹ Latinh đã thực hiện một vai trò

chính trị rõ ràng trong việc bảo vệ người dân khỏi sự áp bức của

phát xít và giúp tổ chức cuộc phản công. Phong trào này được gọi là

thần học giải phóng. Otto Maduro (1982) coi đây là một ví dụ về cách

các tổ chức tôn giáo có thể cung cấp sự hướng dẫn cho giai cấp công

nhân và những người bị áp bức khi họ đấu tranh với giai cấp thống

trị. Thay vì là một lực lượng bảo thủ, Giáo hội Công giáo tại địa

phương đã thực hiện một vai trò cách mạng ở các quốc gia như El

Salvador và Guatemala trong cuộc chiến chống lại chế độ độc tài quân