Trang Chủ . Kim Âu . Lưu Trữ. Báo Chí . RFI . RFA . Tác Giả . Chính Trị . Văn Nghệ . Khoa Học . Mục Lục . Quảng Cáo . Photo . Photo 1. Tinh Hoa . ***

Lost Commandos

Win Last Battle

U.S. Senate approves reparations for Vietnamese espionage unit

BACK FROM THE DEAD: Former South Vietnamese commandos (left to right) Sang Xuan Nguyen, Bui Quang Cat, Son Van Ha, and Hoc Van Mai, meet at Mai's San Jose home to discuss the U.S. Senate action granting the commandos $20 million in reparation payments. photo by Vu Van Loc

by Bert Eljera

Back in the summer of 1967, Son Van Ha was an adventurous 19-year-old South Vietnamese Army commando eager to do battle with the North Vietnamese Communists.

He was a member of an elite unit, called spy commandos, trained by the CIA to conduct intelligence and sabotage missions deep into North Vietnam.

On his first mission, however, Ha and his 10-man team, which included two American officers, were captured by the North Vietnamese while gathering information on enemy troop movements near the North Vietnam-Laos border.

For the next 20 years, Ha endured "barbaric" conditions at a North Vietnamese prison. But worst of all, he was declared dead, virtually forgotten by the U.S. government that financed his mission.

Ha was finally released from prison in 1987, 12 years after the Vietnam War ended. Lost, middle-aged, and his parents both dead, Ha wandered about in Ho Chi Minh City until arriving in the United States in 1994.

Now living in Atlanta, Ha, 48, is among 281 former commandos seeking compensation from the U.S. government, which had refused to acknowledge their existence throughout the Vietnam War and for years afterward.

But, a lawsuit in 1986 and recent declassified military documents have uncovered the "Lost Commandos." Last week, in a dramatic move, the U.S. Senate authorized a $20 million reparations program for the commandos.

Using words like "atrocity," "betrayal," and "indefensible" in describing the men's treatment by the U.S. government, the senators voted to provide lump-sum payments of up to $40,000, or $2,000 a year for every year the commando was in prison.

"This conduct [by U.S. government officials] seems to be totally indefensible," said Sen. Alan Specter, R-Pa., chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, which conducted hearings on the commandos. "I have grave doubts that this money is enough. This conduct is criminal."

Sen. John Kerry, D-Mass., a decorated Vietnam veteran, introduced legislation that would provide the reparation payments. His bill applies specifically to South Vietnamese commandos who infiltrated North Vietnam to gather intelligence and conduct sabotage missions.

Kerry's bill is attached as an amendment to the Defense Authorization Bill of 1997, which President Clinton has promised to support. The House of Representatives has yet to approve the bill.

About half of the surviving commandos are already in the United States, said Ha, who was in San Jose last week to meet with former commandos living in the Bay Area. Although more than 80 are still in Vietnam, all commandos and the heirs of those who have died will be eligible for the reparation payments, according to Ha.

"It's not the money that we care about," said Ha, who is general secretary of the Vietnamese Community of Georgia, which assists Vietnamese refugees. "We were written off as dead, but we want the U.S. government to recognize us."

Moreover, Ha said they want the former commandos still in Vietnam and their families to be allowed to immigrate to the United States.

"It's the least the U.S. can do," said Ha, who testified before the U.S. Senate last week. "I'm 48, and I'm probably the youngest. The others are in their 50s and 60s, some in their 70s. We can't get our lives back, but we can regain our honor."

A former U.S. Army intelligence officer has been credited for bringing the plight of the former commandos to public attention in the United States.

Sedgwick Tourison, who served in Laos, Vietnam, and Thailand during the Vietnam War, came back in 1983 to work at the Pentagon as a civilian intelligence officer dealing with POWs and MIAs in Southeast Asia.

The reports of POW sightings led nowhere, but Tourison, who is married to a Vietnamese, kept receiving information about South Vietnamese commandos apparently abandoned after they were captured by the North Vietnamese.

In 1985, he met his first commando: Le Van Ngung, who was captured in 1967, had just arrived in Baltimore. Through Ngung, Tourison met other commandos.

"Neither Ngung nor I had any idea at the time what really happened," Tourison said in a telephone interview last week from his home in Crofton, Md., just outside Annapolis, where he now works as a master jeweler.

"It became a puzzle," he said. "The puzzle was partially solved in 1992 when a top secret history of the commando operations was declassified in a joint decision by the CIA, the defense department, and the department of state."

Tourison worked with the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Prisoners of War and Missing in Action from 1991 to 1993, allowing him the opportunity to review the secret commando program.

From the declassified military documents and interviews with the commandos, Tourison wrote a book, titled Secret Army, Secret War, which was published by the Naval Institute Press in 1995.

"It was obvious that these people should have been compensated and this was something the government has covered up for 30 years," Tourison said. "I believe there was a reason to go to court."

While working with the Select Committee on POWs and MIAs, Tourison met John C. Mattes, a Miami lawyer and staff attorney of the committee.

When their services with the committee ended, Tourison and Mattes decided to work together on behalf of the commandos. Mattes filed a suit for reparations with the U.S. Claims Court in April 1995, and Tourison continued to contact former commandos in the United States, Vietnam, and other countries.

Tourison said that nearly 200 former commandos are living overseas: 190 in the U.S.; one in China; one in Denmark; one in Holland; three in Australia; and one in Thailand. There are 89 left in Vietnam.

In addition, he said he has located 93 widows and heirs of dead commandos. The North Vietnamese government announced in 1995 that they had captured or killed 463 commandos.

Tourison, who testified before the U.S. Senate last week, said that regardless of where the commandos or their heirs are living right now, they are all entitled to compensation.

"It's the right thing to do," Tourison said. "We lied to them."

Mattes said he is confident the U.S. Congress will approve the reparations program. If that happens, the suit with the U.S. Claims Court would be withdrawn.Otherwise, he will pursue the lawsuit, which he claims now has an excellent chance of being decided in his favor, following the Senate action and the release of recent declassified documents.

This month, the Pentagon has released employment records of the commandos, confirming that they were paid salaries and other benefits by the U.S. government, he said.

"The secret was preserved up through 1993," said Mattes, who now practices law in Miami. "The fundamental question for the court is: Will we acknowledge them and their place in history? To acknowledge them is to pay them."

The Pentagon, the U.S. Department of Justice, and the CIA have asked the U.S. Claims Court to dismiss the suit.

It was a similar claim for benefits by a former commando that brought the story of the Vietnamese commandos to public attention in the United States for the first time.

In 1986, Vu Duc Guong, who escaped from a Communist prison in 1980 and made his way to the United States, filed a claim for about $500,000 in back wages and interest with the U.S. Claims Court.

In addition, Guong sought $21 million in damages because the United States was obligated to repatriate him from a North Vietnamese prison and had failed to do so, according to his lawyer, Anthony J. Murray Jr. of Chicago.

But the U.S. Claims Court dismissed the suit, ruling that Goung had participated in an undercover operation sponsored by the U.S. government, and no action can be brought to enforce a secret contract.

The ruling was based on an 1875 U.S. Supreme Court decision that barred the estate of a spy for Abraham Lincoln from collecting payment for work performed during the Civil War.

"Both employer and agent must have understood that the lips of the other were to be forever sealed," the high court ruled.

But Mattes argues that the veil of secrecy has since been lifted because some of the Pentagon documents have been declassified and the fate of the commandos has been published in books and newspaper articles.

Mattes suggests that acknowledging the existence of the commandos would alter the widely accepted view that the U.S. escalated the war as a result of the Gulf of Tonkin incident on Aug. 2, 1964.

North Vietnamese patrol boats allegedly attacked the U.S. destroyer USS Maddox without provocation, leading to the congressional passage of the Tonkin Resolution that allowed then-President Lyndon Johnson to step up American involvement in Vietnam.

Declassified documents now show that South Vietnamese commandos operated in the area under the direction of the Americans.

"The U.S. always want to portray the Vietnam War as a war we were just assisting," Mattes said. "But I'm not here to say what caused what. I only represent the commandos, not interpret history. "I felt there was an injustice to look for [American] POWs and forget those who served with us just because they were Asian," he added.

One commando, Sang Xuan Nguyen, now 61, said he was captured by the North Vietnamese in December 1963, well before the Tonkin incident.

A 28-year-old South Vietnamese Army sergeant at the time, Nguyen said he volunteered for the commando unit because of the extra pay and the prestige of being a member of the elite force.

The commandos were paid three times the amount of ordinary South Vietnamese soldiers. They could wear any military uniform they wished, had no military ranks, and were granted privileges such as chauffeur-driven cars.

Nguyen said the training was secret and rigorous. He said he was trained as a communication expert for nine months before being dropped in North Vietnam as a member of a seven-man intelligence unit.

The unit was captured within a week before it could accomplish its mission, Nguyen said. "It looked like Hanoi knew what was going on," he said. "There was an information leak from the south."

His unit was taken to a local jail in Quang Binh Province, Nguyen said. A military court tried them as traitors, and each was sentenced to 20 years in jail.

Nguyen was released in 1983, but three members of his team died in prison. "It was terrible," Nguyen said through an interpreter. "For the first 10 years, we were never allowed outside for fear that we would escape."

Even after the war ended in 1975, he said they were placed in single cells and shackled. "It was terrible," he said. "The food was not fit for humans."

His family was told he was dead. His four children, including a daughter who was born after his capture in 1963, were all grown up when he returned 20 years later. His wife had remarried.

"I lost everything," said Nguyen, who arrived in the United States just last week and now lives with friends in San Jose.

Ha, Nguyen, and others like them were recruited to join a program dubbed "Operation Plan-34 Alpha," which the CIA began in 1961, according to the declassified documents.

Over the next decade, the CIA spent more than $100 million to train and send about 500 Vietnamese agents to infiltrate North Vietnam, but most ended up in prison camps.

One declassified report contains testimony before the Joint Chiefs of Staff in which those responsible for the plan knew the men were prisoners but decided to tell their families they were killed to reduce program costs.

"We reduced the number [on the payroll] gradually by declaring so many of them dead each month until we had written them off and removed them from the monthly payroll," Marine Col. John J. Windsor testified.

Ha said he himself was declared dead and his parents were paid, although he did not know how much.

"I saw the document with my father's signature on it that said he received my death benefits," said Ha, who was an only child. His parents are now both dead.

But what the Pentagon officials did not anticipate was for many former commandos, such as Ha, to survive the prison camps and make their way to the United States.

"These commandos are no longer young," Tourison said, adding that one commando now living in Stockton is 82 years old. "They cannot wait another 30 years. They need help now."

But some defense officials argue that providing back-pay to the Vietnamese commandos would set a bad precedent. This might open the door for other forces supported by the U.S. government, such as the Contras of Nicaragua and the Cubans in the Bay of Pigs, to seek compensation.

In his testimony before the U.S. Senate last week, retired Army Maj. Gen. John K. Singlaub, who was a colonel in 1965 headed the defense department unit that wrote off the commandos, said the Vietnamese commandos are not entitled to compensation.

"They were recruited by the Vietnamese," Singlaub said. "We were less than a full partner in this particular operation."

Singlaub said the program was a failure from the start because a spy had infiltrated it and was sending information to the North Vietnamese.

But Mattes and Tourison insist that that was not an excuse to leave the commandos behind and not work for their release when the U.S. signed the agreement with North Vietnam ending the war in 1975.

"We knew exactly what happened to them," Mattes said. "And we lied to their families."

This "betrayal" is the hardest to accept, according to Hoc Van Mai, 55, who is also now a San Jose resident..

"We fought a secret war," said Mai, a logistical officer with the South Vietnamese Army when he joined the commandos in 1963. "We had no name, no fame, and when it was over, we were abandoned."

Mai spent 20 years in a Communist labor camp, escaped in 1982, but was arrested again after trying to organize opposition to the Vietnamese government.

After spending four more years in prison, he escaped again. In 1985, Mai joined the exodus of boat people leaving Vietnam. After one year at a refugee camp in the Philippines, he was admitted into the U.S.

For the past three years, he has been active in rallying support for the commandos. He joined in the class-action suit to force the U.S. government to recognize them.

"We have to raise the issue and tell our story," said Mai, who hosted the meeting last week with Ha and other commandos at his San Jose home.

But telling the story is still an emotional and gut-wrenching experience for most commandos. Many have refused to open up, even to their family members.

Bui Quang Cat, 56, who lives in San Jose with his wife and two children, still finds it difficult to describe the 17 years he spent in a Communist labor camp.

"He does not want his family to know the pain he endured in prison," said Phan Nguyen, a family friend.

With Nguyen interpreting, Bui said he was only 26 years old, a civilian employee of the South Vietnamese Information Ministry, when he was sent as a spy into North Vietnam in 1966. He was captured within a month, after the North Vietnamese were apparently tipped off about his mission.

"I don't mind that I was captured; it was war," Bui said. "But, at least our sacrifices should have been recognized."

For Ha, who now works as a forklift operator in Atlanta, the gung-ho spirit of his youth is all gone. The "barbaric Communist prison has seen to that.

He was captured just a few days after his team was dropped near Laos. His team leader, an American officer, was beaten to death while they were being transported to Hanoi.

Some members of his team were released back in 1973, but he stayed until 1987. Even after the war ended in 1975, he was shackled and kept in solitary confinement.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

©1998 AsianWeek. The information you receive on-line from AsianWeek is protected by the copyright laws of the United States. The copyright laws prohibit any copying, redistributing, retransmitting, or repurposing of any copyright-protected material.

Last Lines of Defense

|

Photo by Eric Lachica |

|

Chain Reaction: Filipino WWII veterans chained themselves in front of the White House last July to protest the delay in benefits. South Vietnamese and Laotian vets have joined them in demands for equal veterans benefits. |

Veterans benefits become a key civil rights issue for APA groups

BY BERT ELJERA

Filipino soldiers fought in some of the fiercest battles in the Pacific during World War II. And when their American commanders ordered them to surrender to the invading Japanese forces, they endured the infamous "Bataan Death March." Later, many of them took to the hills and waged a guerrilla war.

After the war, they were declared ineligible for benefits under the G.I. Bill and other laws. Now more than 50 years later, they are still seeking formal recognition as U.S. veterans as well as the accompanying benefits.

South Vietnamese commandos were recruited by the Central Intelligence Agency for sabotage and intelligence missions deep inside North Vietnam. When they were captured, their U.S. officers declared them dead and forgot about them until long after the end of the Vietnam War. They were on the Pentagon payroll and never formally discharged from military service, yet they are not considered U.S. veterans.

Laotians and Hmongs are a gentle people, proud of their independence and simple ways. American officers recruited them to fight the Communists and help rescue downed U.S. pilots during the Vietnam War. They were lauded for their bravery, loyalty, and fierce anti-communist spirit. But they too are not considered U.S. veterans and, in fact, could now lose their primary source of sustenance--food stamps.

All of these soldiers are Asians. All fought under the U.S. flag. Yet none receives benefits enjoyed by other U.S. veterans. More and more are asking for an explanation.

The answer is as complicated as the era in which the United States was at war. World War II was fought more than a half-century ago. Most Americans do not have a recollection of that conflict. The Vietnam War does not conjure happy memories for the American public; it might as well be forgotten.

Advocates within the Asian American community say that political expediency, the enormous cost, and public apathy have conspired to push these veteran's issues off of the nation's radar screens.

Some say it's a question of fairness that national leaders have yet to fully address. And time is running out.

"When we ask someone to stand with us, fight with us under our flag, we should not turn and run away from them when they seek our assistance," said John Mattes, a Miami lawyer who is spearheading the effort to obtain veteran status for former South Vietnamese soldiers. "That is cowardly."

A little history helps to clarify the issues. In the case of Filipino veterans, they were inducted into the U.S. Army under a military order issued by President Roosevelt on July 26, 1941. At that time, the Philippine Islands were a colony of the United States.

About 120,000 members of the Commonwealth Armed Forces of the Philippines were merged with the 12,000-strong Philippine Scouts and 10,000 U.S. Army regulars to form the first line of defense against the advancing Japanese.

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the troops made a stand at Bataan and Corrigidor. The Filipino soldiers, fighting side by side with their U.S. comrades, held off the Japanese for five months, allowing the U.S. to prepare for the defense of Australia and the eastern Pacific.

When Bataan and Corrigidor fell in 1942, many of the Filipino soldiers became guerrilla fighters, harassing the Japanese and providing intelligence information to their American officers. Their work helped smooth the return of Gen. Douglas MacArthur to the Philippines to liberate the islands in 1944.

In the latter part of 1945, the U.S. Veterans Administration (VA) tried to determine how much it would cost to provide veterans benefits to the Filipino soldiers. The VA administrator at the time, Gen. Omar Bradley, estimated that it would cost the U.S. $3.2 billion to compensate the veterans and eligible family members.

Because of the enormous cost, the U.S. Congress decided to pass the Rescission Act of 1946, stating that military service under the Philippine colonial government was not considered active service in the U.S. Armed Forces.

The U.S. Congress allocated $200 million for partial benefits, including service-related disability, death, and life insurance. The Filipino veterans were classified under four categories: Regular Philippine Scouts, who enlisted with the U.S. Armed Forces before Oct. 6, 1945; Special Philippine Scouts, whose service began on or after Oct. 6, 1945; and members of the Commonwealth Army of the Philippines. The fourth category recognized guerrillas, who supported U.S. forces from April 1942 to June 1946.

In all, nearly 200,000 Filipinos fought under the U.S. flag. About 70,000, now mostly in their 70s and 80s, are still alive, .

Only the Regular Philippine Scouts receive the full range of veterans benefits, while those in the other categories receive 50 cents for every dollar authorized in monetary compensation.

Patrick Ganio, who heads the Washington, D.C-based American Coalition for Filipino Veterans (ACFV), said Filipinos were singled out for denial of full benefits, while 116,000 alien veterans from 66 foreign countries that fought in the same situation were granted full benefits.

"Unless and until the law is rectified to correct the wrong done to Filipino veterans, the claim for equalized benefits remain unresolved," Ganio said. "To the Filipino veterans now in the twilight of their lives, time is running out."

A veterans equity bill has been filed in the U.S. Congress since 1989, but none has succeeded in securing benefits for the Filipino veterans. Legislators made an overture by adopting an amendment to the 1990 Immigration Law that allowed about 26,000 Filipino veterans to become U.S. citizens.

Although now U.S. citizens, they are still denied benefits available to other U.S. veterans. Ken McKinnon, a spokesman for the Department of Veteran Affairs, said that veteran status is not based on citizenship, but on military service.

Since the U.S. Congress declared back in 1946 that service in the Philippine Commonwealth Forces and the guerrilla movement was not considered active service in the U.S. military, Filipinos do not have the status of U.S. veterans, McKinnon said.

"We provide benefits to veterans as provided by law," McKinnon added. "We do not make the policies; we implement them."

The Filipino Veterans Equity Bill hopes to do just that. Authored by Sen. Daniel Inouye, D-Hawaii, in the U.S. Senate and Rep. Bob Filner, D-Calif., in the House of Representatives, the bill seeks to give Filipino veteran parity with other U.S. veterans.

Again, the bill is given slim chance of passage this year. Eric Lachica, executive director of the American Coalition for Filipino Veterans, said 50 senators and 216 representatives must co-sponsor the legislation to ensure its passage.

So far, 11 senators and 176 representatives have signed on, but there's a long way to go. "What we're asking for is something we should have gotten back in 1946," Lachica said. "It's about time [the U.S.] comes through with its promises and obligations."

Last month brought some good news. The Senate Veterans Affairs Committee voted to provide burial benefits to naturalized Filipino veterans who reside in the United States.

Sen. Daniel Akaka, D-Hawaii, who sits on the committee said it was a small but significant concession toward granting the Filipino veterans their due.

"Providing full burial benefits to Filipino veterans who fought alongside our men in the Philippine Islands is a small, but symbolic first step toward equity," Akaka said in a prepared statement.

Filipino veterans recently opened a new front in their quest to secure full benefits. They filed a lawsuit against the federal government, seeking full benefits and back pay.

"You can only sit down and wait for so long," said the veterans' lawyer, William Salica from Los Angeles. "These plaintiffs don't have much time to wait."

The suit in Los Angeles Superior Court was filed on behalf of 220 former military personnel all living in the United States.

The South Vietnamese commandos have also used the courts and the U.S. Congress to demand compensation and recognition as U.S. veterans. Last year, legislators approved a $20-million compensation package to be paid out to the commandos, each receiving an average of $20,000. Claims are now being processed and could be disbursed before the end of the year, according to Mattes, the commandos' lawyer.

About 200 of the estimated 350 commandos who have been identified now live in the United States.

But Mattes said he is working toward recognition for former soldiers as U.S. veterans entitled to medical care, housing loans, student loans, job training, and other benefits.

He said he has petitioned the Pentagon to classify his clients as U.S. veterans. Failing that, he said he's willing to go to court or to the U.S. Congress to secure the benefits.

"These men were on the payroll as combat employees of the United States," Mattes said. "They are eligible to gain veteran status."

It was through Mattes' work and that of a former U.S. intelligence officer that the plight of the commandos became known. The CIA and, later, the U.S. Army botched the spy operations in North Vietnam and many of the soldiers were captured after they parachuted behind enemy lines. Recent declassified documents indicate that U.S. officers declared them dead, and their families were provided burial compensation and other benefits.

Mattes said that documents recently made public show that the commandos were "killed off " to reduce cost, even though there was evidence the men were being held in Communist prisons.

Although the Vietnam War ended in 1975, many of the commandos were still in prison camps until the mid-1980s. Sang Xuan Nguyen, who now lives in San Jose, said they were placed in single cells and shackled.

"We were never allowed outside for fear that we would escape," Nguyen said. "It was terrible. The food was not fit for humans."

Mattes said it's critical for the commandos to receive medical care, especially now that they are advancing in age. "Medicaid--which the commandos receive--does not address the battle wounds and torture these people suffered," he said. "These men are wounded and need specialized care."

That could be achieved by declaring them U.S. veterans, Mattes said. "The evidence is overwhelming," he said. "We have the physical payrolls and the persons who engaged in combat. There can't be a clearer case than that."

He said that if the petition, which was sent to the Pentagon in September, is denied, he will go to court to compel the military to recognize the commandos as veterans.

"This country could do the right thing," Mattes said, adding that the same treatment could not be done to white POWs or to minority groups other than Asians. "Sometimes, we have to bring out our government kicking and screaming to provide justice."

In a sense, the Hmongs and Laotians are doing just that. They are using the courts, with help from the Asian Law Caucus, to keep their food-stamp benefits, which the new welfare reform law has taken away.

Under last year's welfare reform act, noncitizens, except those who meet limited exceptions such as veterans, are barred from receiving food stamps.

According to Asian Law Caucus attorney Victor Hwang, there is a sense in Congress that Hmongs and other Highland Lao veterans who fought on behalf of the U.S. Armed Forces during the Vietnam conflict should be considered veterans for purposes of continuing certain welfare benefits.

About 50 Hmong and Lao veterans whose benefits were terminated earlier this month are testing the language of the law at a municipal court in Marysville, Calif.

"All they're asking is not to be cut off from welfare," Hwang said. "They should be given veteran status. They thought the welfare checks and benefits were money they earned for fighting for the U.S. They said it was OK to send 100 Hmongs to die to save the life of one American soldier. They literally killed themselves to save American lives."

He said the welfare benefits were practically "bribes" to them for the past 20 years. "Now, you turn around and say, 'get a job."'

According to the 1990 census, there are about 100,000 Hmongs in the United States, with nearly half (43,000) living in California. There are about 150,000 Laotians, again mostly in California, particularly Fresno, San Diego, and Sacramento.

A mountain people with limited education, about 60 to 70 percent of Hmongs and Laotians are on welfare, according to Hwang, who is representing many of them in appeals to keep their food stamps.

"They are some of the most loyal anti-Communists that you can find," Hwang said. "Some say, their only useful skill was killing people. Now that it's peacetime, they don't need that skill--and they have nothing else."

Yee Xiong, president of the California Statewide Lao/Hmong Coalition, said his people have suffered long enough. "The Hmong people were targeted for persecution and execution in Laos because of their service on behalf of the CIA," Xiong said. "Many have sacrificed the lives of their parents, brothers, sisters, sons, and daughters on the promise the United States would care for their families. All we ask is to honor that promise."

|

|

|

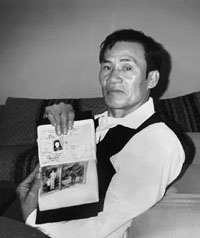

"Lost Commando" Bui Quang Cat shows a photo of himself as a young recruit in American military training in Saigon. He was captured on a 1966 mission in North Vietnam and spent 17 years in a labor camp. He now lives with his wife and two children in San Jose, Calif. |

From 1961 to 1975, the Hmongs and Laotians were recruited and trained to fight the North Vietnamese Army and rescue pilots shot down in Laos and Vietnam. By some accounts, as many as 150,000 fled their country at the end of the war when the Communists took over. They were resettled in Minnesota, Wisconsin, California, and other places. In September, the veterans were honored at a ceremony in Wisconsin for their sacrifices during the Vietnam War.

But according to McKinnon, the Department of Veterans Affairs spokesman, the agency has fought against granting veteran status for those who have not served actively in the U.S. military.

"You need to show a discharge document from the military service," McKinnon said. "If it's an honorable discharge, then you may be entitled to certain benefits."

The benefits include disability compensation, pension, burial benefits, home loan guarantees, small-business loans, hospitalization and health care, and education under the G.I. Bill.

Stephen L. Lemons, the acting undersecretary for benefits at the Department of Veterans Affairs, said they have opposed the Filipino Veterans Equity Bill because the current Philippine law for veterans is as comprehensive as that authorized by U.S. laws.

"There is no question that Filipino forces, fighting to preserve the independence of their homeland, contributed to the allied victory in the Pacific," Lemons said in a testimony before the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee in July.

"However, current law appropriately recognizes our two nations' shared responsibility for their well-being and should not be changed," Lemons said.

In addition, he said the health-related components of the bill would cost an estimated $1.6 billion in fiscal 1998 and $7.5 billion over five years.

But Filipino veterans advocates say the estimates are inflated. For one thing, only about 70,000 of the veterans are still alive, and less than half of them are U.S. citizens.

"What's so unfair is that they are looked upon as less than equal to other American servicemen," said Lachica, the ACFV executive director.

He added, however, that the strong opposition from even the Department of Veterans Affairs, which should be an advocate, will not deter them from seeking parity.

The decision to provide burial benefits for Filipino veterans in the U.S. is an encouraging sign.

"It's a very small concession, but it chips away at the 1946 Rescission Act," Lachica said. "But we're aiming higher. They deserve to get those benefits."

But Mattes is less diplomatic. He said racism is the reason why the Asian veterans are not recognized for what they are--U.S. veterans.

"It's so easy to turn our backs on people who are not white or Anglos," he said. "Let's be honest, if this happened to white Anglo soldiers, do you think the Pentagon would be as callous?"

©1998 AsianWeek. The information you receive on-line from AsianWeek is protected by the copyright laws of the United States. The copyright laws prohibit any copying, redistributing, retransmitting, or repurposing of any copyright protected material.

█ JUDSON KNIGHT

The Vietnam War was a struggle between communist and pro-western forces that lasted from the end of World War II until 1975. The communist Viet Minh, or League for the Independence of Vietnam, sought to gain control of the entire nation from its stronghold in the north. Opposing it were, first, France, and later the United States and United Nations forces, who supported the non-communist forces in southern Vietnam. In 1975, in violation of a 1973 peace treaty negotiated to end United States military involvement in South Vietnam and active war against North Vietnam, North Vietnamese forces and South Vietnamese communist sympathizers seized control of South Vietnam

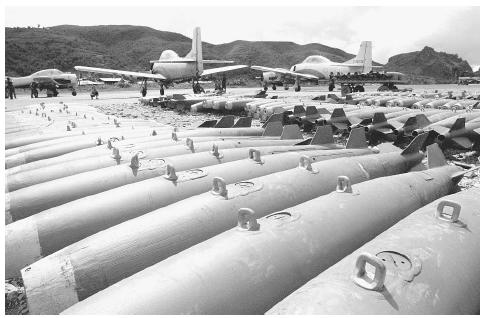

Converted T-28 trainer aircraft and 250-pound bombs used by Meo pilots of Vang Pao's "mini-Air Force," a CIA-sponsored unit that fought against the North Vietnamese in northern Laos in 1972. ©

BETTMANN/CORBIS

.

and reunited the two countries into a single communist country.

American involvement in Vietnam has long been a subject of controversy. The fighting depended, to a greater extent than in any conflict before, on the work of intelligence forces. Most notable among these were various U.S. military intelligence organizations, as well as the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

Early stages. Led by Ho Chi Minh (1890–1969), the Viet Minh aligned themselves with the Soviets from the 1920s. However, they configured their struggle not in traditional communist terms as a class struggle, but as a war for national independence and unity, and against foreign domination. Vietnam at the time was under French control as part of Indochina, and World War II provided the first opportunity for a Viet Minh uprising against the French, in 1940. France, by then aligned with the Axis under the Vichy government, rapidly suppressed the revolt. Nor did the free French, led by General Charles de Gaulle, welcome the idea of Vietnamese independence.

After the war was over, de Gaulle sent troops to resume control, and fighting broke out between French and Viet Minh forces on December 19, 1946. On May 7, 1954, the French garrison at Dien Bien Phu fell to the Viet Minh after an eight-week siege. Two months later, in July 1954, the French signed the Geneva Accords, by which they formally withdrew from Vietnam.

The Geneva Accords divided the country along the 17th parallel, but this division was to be only temporary, pending elections in 1956. However, in 1955 Ngo Dinh Diem declared the southern portion of the nation the Republic of Vietnam, with a capital at Saigon. In 1956, Diem, with the backing of the United States, refused to allow elections, and fighting resumed. The conflict was now between South Vietnam and the communist republic of North Vietnam, whose capital was Hanoi. Fighting the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) were not only the regular army forces of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), but also Viet Cong, guerrillas from the South who had received training and arms from the North.

American involvement. President Dwight D. Eisenhower had already sent the first U.S. military and civilian advisers to Vietnam in 1955, and four years later, two military advisers became the first American casualties in the conflict. The administration of President John F. Kennedy greatly expanded U.S. commitments to Vietnam, such that by late 1962 the number of military advisers had grown to 11,000. At the same time, Washington's support for the unpopular

Diem had faded, and when American intelligence learned of plans for a coup by his generals, the United States did nothing to stop it. Diem was assassinated on November 1, 1963.

Under President Lyndon B. Johnson, U.S. participation in the Vietnam War reached its zenith. The beginnings of the full-scale commitment came after August 2, 1964, when North Vietnamese gunboats in the Gulf of Tonkin attacked the U.S. destroyer Maddox. Requesting power from Congress to strike back, Johnson received it in the form of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which granted the president virtual carte blanche to prosecute the war in Vietnam.

High point of the war. As a result of his strengthened position to wage war, and still enjoying broad support from the American public, Johnson launched a bombing campaign against North Vietnam in late 1964, and again in March 1965, after a Viet Cong attack on a U.S. installation at Pleiku. By June 1965, as the first U.S. ground troops arrived, U.S. troop strength stood at 50,000. By year's end, it would be near 200,000.

General William C. Westmoreland, who had assumed command of U.S. forces in Vietnam in June 1964, maintained that victory required a sufficient commitment of ground troops. Yet by the mid-1960s, the NVA had begun moving into the South via the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and as communist forces began to take more villages and hamlets, they seemed poised for victory. Johnson pledged greater support, but despite growing number of ground troops and intensive bombing of the North in 1967, U.S. victory remained elusive.

The turning point in the U.S. effort came on January 30, 1968, when the NVA and Viet Cong launched a surprise attack during celebrations of the Vietnamese lunar new year, or Tet. The Tet Offensive, though its value as a military victory for the North is questionable, was an enormous psychological victory that convinced Americans that short of annihilation of North Vietnam—an unacceptable geopolitical alternative—they could not win a Korea-like standoff or outright victory in Vietnam. In March 1968, Johnson called for an end to bombing north of the 20th parallel, and announced that he would not seek reelection. Westmoreland, too, was relieved of duty.

Withdrawal (1969–75). The administration of President Richard Nixon in 1969 began withdrawing, and instituted a process of "Vietnamization," or turning control of the war over to the South Vietnamese. In 1970, the most significant military activity took place in Cambodia and Laos, where U.S. B-52 bombers continually pounded the Ho Chi Minh Trail in an effort to cut off supply lines.

Despite the bombing campaign, undertaken in pursuit of Vietnamization and the goal of making the war winnable for the South, the North continued to advance. On January 27, 1973, the United States and North Vietnam signed the Paris Peace Accords, and U.S. military involvement in Vietnam ended.

During the two years that followed, the North Vietnamese gradually advanced on the South. On April 30, 1975, communist forces took control of Saigon as government members and supporters fled. On July 2, 1976, the country was formally united as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, and Saigon renamed Ho Chi Minh City.

The intelligence and special operations war. Behind and alongside the military war was an intelligence and special operations war that likewise dated back to World War II. At that time, the United States, through the Organization of Strategic Services (OSS), actually worked closely with Viet Minh operatives, who OSS agents regarded as reliable allies against the Japanese. Friendly relations with the Americans continued after the Japanese surrender, when OSS supported the cause of Vietnamese independence.

This stance infuriated the French, who sought to reestablish control while avoiding common cause with the Viet Minh. They attempted to cultivate or create a number of local groups, among them a Vietnamese mafia-style organization, that would work on their behalf against the Viet Minh. These efforts, not to mention the participation of one of the world's most well-trained special warfare contingents, the Foreign Legion, availed the French little gain.

Special Forces, military intelligence, and CIA. In the first major U.S. commitment to Vietnam, Kennedy brought to bear several powerful weapons that together signified his awareness that Vietnam was not a war like the others America had fought: the newly created Special Forces group, known popularly as the "Green Berets," as well as CIA and a host of military intelligence organizations.

Though Special Forces are known popularly for their prowess in physical combat, their mission in Vietnam from the beginning had a strong psychological warfare component. In May 1961, Kennedy committed 400 of these elite troops to the war in Southeast Asia, and more would follow.

Alongside them, in many cases, were military intelligence personnel, whose ranks in Vietnam numbered 3,000 by 1967. Most of these were in two army units, the Army Security Agency (ASA) and the Military Intelligence Corps. The work of military intelligence ranged from the signals intelligence of ASA, one of whose members became the first regular-army U.S. soldier to die in combat in 1961, to the electronic intelligence conducted by navy destroyers such as the ill-fated Maddox. In addition, military aircraft such as the SR-71 Blackbird and U-2 conducted extensive aerial reconnaissance.

As for CIA, by the time the war reached its height in the mid-to late 1960s, it had some 700 personnel in Vietnam. Many of these operated undercover groups that included the Office of the Special Assistant to the Ambassador (OSA, led by future CIA chief William Colby), which occupied a large portion of the U.S. Embassy in Saigon.

Cooperation and conflict. These three major arms of the intelligence and special operations war—Special Forces and other elite units, military intelligence, and CIA—often worked together. When Kennedy sent in the first contingent of Special Forces, they went to work alongside CIA, to whom the president in 1962 gave responsibility for paramilitary operations in Vietnam.

Unbeknownst to most Americans, CIA was also in charge of paramilitary operations in two countries where the United States was not officially engaged: Cambodia and Laos. Long before Nixon's campaign to cut off the Ho Chi Minh Trail with strategic bombers, CIA operatives were training a clandestine army of tribesmen and mercenaries in Laos. Ordinary U.S. troops were not involved in this sideshow war in the interior of Southeast Asia: only Special Forces, who—in order to conceal their identity as American troops—bore neither U.S. markings nor U.S. weaponry.

CIA and army intelligence personnel worked on another notorious operation, Phoenix, an attempt to seek out and neutralize communist personnel in South Vietnam during the period from 1967 to 1971. CIA claimed to have killed, captured, or turned as many as 60,000 enemy agents and guerrillas in Phoenix, a project noted for the ruthlessness with which it was carried out. In this undertaking, CIA and the army had the nominal assistance of South Vietnamese intelligence, but due to an abiding U.S. mistrust of their putative allies, the Americans gave the Saigon little actual role in Phoenix.

The military and CIA debacles. In other situations, CIA and military groups did not so much intentionally collaborate as they found themselves thrown together, often at cross-purposes, or at least in ways that were not mutually beneficial. While U.S. Navy destroyers in the Gulf of Tonkin were monitoring North Vietnamese electronic transmissions, CIA was busy striking at Viet Minh naval facilities with fast craft whose South Vietnamese (or otherwise non-American) crews made CIA involvement deniable. But North Vietnamese intelligence was as capable as its military, and they fired on the Maddox in direct response to this CIA operation.

The U.S. military became involved in another CIA debacle when, in 1968, army intelligence tried to resume a failed effort by CIA's Studies and Observation Group (SOG), another cover organization. From the early 1960s, SOG had been attempting to parachute South Vietnamese agents into North Vietnam, with the intention of using them as saboteurs and agents provocateur. The effort backfired, with most of the infiltrators dead, imprisoned, or used by the North Vietnamese as bait. CIA put a stop to the undertaking, but army intelligence tried to succeed where CIA had failed—only to lose several hundred more Vietnamese agents.

The U.S. Air Force had to take over another unsuccessful CIA operation, Black Shield, which involved a series of reconnaissance flights by A-12 Oxcart spy planes over North Vietnam in 1967 and 1968. Using the A-12, which could reach speeds of Mach 3.1 (2,300 m.p.h. or 3,700 k.p.h.), Black Shield gathered extensive information on Soviet-built surface-to-air missile (SAM) installations in the North. To obtain the best possible photographic intelligence, the Oxcarts had to fly relatively low and slow, and in the fall of 1967 North Vietnamese SAMs hit—but did not down—an A-71. In 1968, the U.S. Air Force, operating SR-71 Blackbirds, replaced CIA.

Assessing CIA in Vietnam. Despite the notorious nature of Phoenix or the CIA undertakings in Cambodia and Laos, as well as the occasions when CIA overplayed its hand or placed the military in the position of cleaning up one of its failed operations, CIA involvement in Vietnam was far from an unbroken record of failure. One success was Air America. The latter, a proprietary airline chartered in 1949, supplied the secret war in the interior, and also undertook a number of other operations in Vietnam and other countries in Asia. That Air America was only disbanded in 1981, long after the war ended, illustrates its effectiveness.

The popular image of CIA operatives in Vietnam as fiends blinded by hatred of communism—an image bolstered by Hollywood—is as lacking in historical accuracy as it is in depth of characterization. Like other Americans involved in Vietnam, members of CIA began with the belief that they could and would save a vulnerable nation from Soviet-style totalitarianism and provide its people with an opportunity to develop democratic institutions, establish prosperity, and find peace. Much more quickly than their counterparts in the military and political communities, however, members of the intelligence community came to recognize the fallacies on which their undertaking was based.

Intelligence vs. the military and the politicians. Whereas many political and military leaders adhered to standard interpretations about the North Vietnamese, such as the idea that they were puppets of Moscow whose power depended entirely on force, CIA operatives with closer contact to actual Vietnamese sources recognized the appeal of the Viet Minh nationalist message. And because CIA recognized the strength of the enemy, their estimate of America's ability to win the war—particularly as the troop buildup began in the mid-1960s—became less and less optimistic.

CIA appraisal of the situation tended to be far less sanguine than that of General Westmoreland and other military leaders, and certainly less so than that of President Johnson and other political leaders far removed from the conflict. In 1965, for instance, CIA and the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) produced a joint study in which they predicted that the bombing campaign would do little to soften North Vietnam. This was not a position favored by Washington, however, so it received little attention.

Whereas Washington favored an air campaign, General Westmoreland maintained that the war would be won by ground forces. Both government and military leaders agreed on one approach: the use of statistics as a benchmark of success or failure. In terms of the number of bombs dropped, cities hit, or Viet Cong and NVA killed, American forces seemed to be winning. Yet for every guerrilla killed, the enemy seemed to produce two or three more in his place, and every village bombed seemed only to increase enemy resistance.

The lessons of Vietnam. In the end, the United States effort in Vietnam was undone by the singularity of aims possessed by its enemies in the North; the instability and unreliability of its allies in the South, combined with American refusal to give the South Vietnamese a greater role in their own war; and a divergence of aims on the part of American leaders.

For example, the Tet Offensive, which resulted in so many Viet Cong deaths that the guerrilla force was essentially eliminated, and NVA regulars took the place of the Viet Cong, is remembered as a victory for the North. And it was a victory in psychological, if not military, terms. The surprise, fear, and disappointment elicited by the Tet Offensive—combined with a rise of political dissent within the United States—punctured America's will to wage the war, and marked the beginning of the end of American participation in Vietnam.

For some time, U.S. college campuses had seen small protests against the war, but in 1968 the number of these demonstrations grew dramatically, as did the ranks of participants. Nor were youth the only Americans now opposing the war in large numbers: increasingly, other sectors of society—including influential figures in the media, politics, the arts, and even the sciences—began to make their opposition known. In the final years of Vietnam, there was a secondary war being fought in the United States—a war concerning America's vision of itself and its role in the world.

By war's end, Vietnam itself had largely been forgotten. Despite earlier promises of a liberal democratic government, the unified socialist republic fell prey to the exigencies typical of communist dictatorship: mass imprisonments and executions, forced redistribution of land, and the banning of political opposition. Forgotten, too, were Laos and even Cambodia, where the Khmer Rouge launched a campaign of genocide that killed an estimated two million people.

The Vietnamese invasion in 1979 probably saved thousands of Cambodian lives, but in the aftermath, Vietnam came to be regarded as a colonialist power. The nation once admired by the third world for standing up to America now became a pariah, supported only by Moscow—which had gained access to a valuable warm-water port at Cam Ranh Bay—and its allies in Eastern Europe.

During the remainder of the 1970s, America was in retreat, its attention turned away from the fate of countries that fell to communism or, in the case of Iran, to Islamic fundamentalist dictatorship. Americans focused their anger on those they regarded as having led them astray during the war years: politicians, the military, and CIA, which came under intense scrutiny during the 1975–76 Church committee hearings in the U.S. Senate. Only in the 1980s, under President Ronald Reagan, did the United States return to an activist stance globally.

█ FURTHER READING:

BOOKS:

Allen, George W. None So Blind: A Personal Account of the Intelligence Failure in Vietnam. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2001.

Conboy, Kenneth K., and Dale Andradé. Spies and Commandos: How America Lost the Secret War in North Vietnam. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2000.

Kissinger, Henry. Years of Renewal. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1999.

Shultz, Richard G. The Secret War against Hanoi: Kennedy's and Johnson's Use of Spies, Saboteurs, and Covert Warriors in North Vietnam. New York: HarperCollins, 1999.

Sorley, Lewis. A Better War: The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America's Last Years in Vietnam. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1999.

Wirtz, James J. The Tet Offensive: Intelligence Failure in War. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991.

ELECTRONIC:

Vietnam War Declassification Project. Gerald R. Ford Library and Museum. http://www.ford.utexas.edu/library/exhibits/vietnam/ (February 5, 2003).

SEE ALSO

CIA (United States Central Intelligence Agency)

Cold War (1950–1972)

Cold War (1972–1989): The Collapse of the Soviet Union

Johnson Administration (1963–1969), United States National Security

Policy

Kennedy Administration (1961–1963), United States National Security

Policy

Nixon Administration (1969–1974), United States National Security Policy

-

U.S. Senate approves reparations for Vietnamese espionage unit

-

Miami Kim Âu

-

Phản Bội Kim Âu

-

Oplan 21 Kim Âu

-

Càn Khôn Đă Chuyển Kim Âu

-

Sự Thật Khách Quan Kim Âu

-

Thẩm Phán Ngu Đần Kim Âu

-